Over 500 New Zealand nurses participated in the First World War. Most enlisted with the New Zealand Army Nursing Service, but around 100 served in other units. Curator and historian Kirstie Ross recounts the story of two of these nurses, Margaret Hitchcock and Lily Lind, whose work with the French Flag Nursing Corps is commemorated in Te Papa’s history collections.

Daisy Hitchcock's collection of trench art. Makers unknown. Gift of Barry Hitchcock. Image courtesy of Te Papa (GH021520-GH021526).

On 23 December 1916, 33-year-old nurse Margaret Hitchcock (Daisy to her friends and family) arrived back in Wellington after serving for two years with the French Flag Nursing Corps. Packed in her luggage were several pieces of trench art. These were tangible reminders of Daisy’s extraordinary experiences, caring for the sick and wounded on the Western Front.

With few examples of military nurses’ tools of the trade surviving the conflict, these seven items are also evidence of a nursing unit in which its members were ‘actively engaged, often under fire.’1 They occupy a unique place in the material record of women’s contributions to the First World War and are now held at Te Papa. (Figure 1)

Daisy’s service, like her souvenirs, differed from the majority of New Zealand’s 500-plus military nurses. Most of these women signed up with the New Zealand Army Nursing Service (NZANS), which was established in February 1915.2 By August, when the first 50 members of the NZANS reached Egypt to work in medical facilities there, Daisy had already been nursing soldiers for nine months in four different hospitals in France and Belgium.

The two nurses had to have passports in order to travel to France. This is Daisy's passport photograph, probably taken in September or October 1914. Reproduced courtesy of Ginny Radford

The distinctive character of Daisy’s service had much to do with her being in the right place at the right time. After training at Wellington hospital (and passing her nursing registration exam in 1909) Daisy and her Southland-born friend Lily Lind travelled to Ireland in 1913 to study midwifery at Dublin’s prestigious Rotunda Hospital. By the time war broke out, the two women had completed their specialist training and were living and working in London as private nurses.

During the first few months of the war, it was generally assumed that the conflict would be over by Christmas. The British War Office therefore advised New Zealand politicians that, because there were enough nurses in Britain to meet the demands of the conflict, New Zealand nursing sisters were surplus to requirements.

Figure 1. Daisy Hitchcock collected this group of trench art while she was working with the French Flag Nursing Corps between 1914 and 1916. Makers unknown. Gift of Barry Hitchcock, 2011. Te Papa (GH021520-GH021526)

However, qualified nurses like Daisy and Lily, and others from around the British Empire who were already living in Britain or could afford to travel there, were free to volunteer their services to existing military nursing units at Home. Many of these units recruited along transnational rather than national lines. One of the most well-known of these was Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (and Reserve), which was established in 1908.

The New Zealand pair, however, joined a newer organisation: the French Flag Nursing Corps (FFNC). The FFNC was a response to France’s shockingly high casualty rate and the shortage of trained nurses available to staff the country’s hospitals. The idea originated with British journalist and feminist Grace Ellison; members of the political, nursing and medical establishment quickly supported her proposal. By October 1914, the Minister of War for France had accepted the offer of 300 nurses under the auspices of the freshly-minted organisation.

.jpg)

Figure 2. Daisy Hitchcock probably acquired this identity bracelet in July 1915 when the hospital barge she was working on stopped at Furnes for a few days. Maker unknown. Gift of Barry Hitchcock, 2011. Te Papa (GH021522)

Daisy and Lily met the three criteria set for French Flag volunteers: they were aged between 28 and 40 years old, had received three years’ training, and were British – the nationality automatically conferred upon New Zealanders, Australians and Canadians.

Potential recruits, however, were warned from the outset that the work they were embarking upon was unsuitable for unqualified novices. The French Minister of War explicitly requested ‘women of ripe experience and very reliable character’.3

Very soon the corps was fully operational. The first group of nine FFNC nurses left England in the last week of October 1914. Daisy and Lily were members of this vanguard.4 (Coincidentally, 19,000 km away, the Main Body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force had only just departed for Europe.)

The two friends were assigned to unit No. 2, which consisted of six nurses from the Registered Nurses Society, and were immediately posted to the Hotel Dieu in Rouen. There they worked alongside French nuns. Lily wrote home that the hospital was ‘terribly full of French, Belgian, Algerian, Turco, and German soldiers. Among the latter I and Miss Hitchcock [sic] are working with French Algerian troops’.5

.jpg)

Figure 3. This alumininum 'Souvenir de Steenvorde' features an engraved picture of a village with a windmill, typical of Flanders. Maker unknown. Gift of Barry Hitchcock, 2011. CC BY-NC-ND licence. Te Papa (GH021520)

FFNC nurses were frequently on the move. By mid-December the pair had moved to a large military hospital in Bordeaux. Then, from the end of January to June 1915, they were posted to the small town of Bergues near the Belgian border. At the poorly-equipped St Union, a former school converted into a hospital, they cared for victims of a typhoid epidemic.

Not only did the nurses have to cope with a lack of basic supplies at St Union; they were also squarely in the firing line. In May 1915, Daisy, Lily, and the four other FFNC nurses at the hospital were subjected to two episodes of intensive artillery bombardments. These devastated buildings close to where they lived and worked: the six survived by sheltering in cellars. The British Journal of Nursing remarked on their pluck: ‘Death exploding at the door one day, the consolation of the teapot in the linen room the next, and every time a good nerve and a good conscience.’6

With their patients safely evacuated from danger, the two friends enjoyed a few weeks’ peace and quiet at the seaside resort of Le Touquet-Paris-Plage (about 5km west of Etaples). While they were resting up, Lily shared news with a friend that she and Daisy had received personal invitations to join the NZANS. But neither nurse was tempted to leave the FFNC: they were ‘very content…with the French’.7

.jpg)

Figure 4. This engraved cup is a souvenir of Steenvorde Hospital where Daisy Hitchcock and Lily Lind worked in 1915. Maker unknown. Gift of Barry Hitchcock, 2011. CC BY-NC-ND licence. Te Papa (GH021521)

Daisy and Lily were soon back at work after their short respite at the beach. In July, they were based in Bourbourg and were assigned to the ‘Service des Evacuations Fluviales’ on ‘Hopital Perniche No. 1’. This was one of two hospital barges that ferried sick and wounded men to hospitals via the canals connecting the Belgian city of Nieuport to Dunkirk and Bourbourg in Flanders.

In a letter written in August 1915, Lily explained that, on the barge, they were ‘always expecting a rush [and] the life is very novel and interesting…. We can carry 52 at a time down the Canal, having 16 stationary beds, and 36 swing ones’.8 The town of Furnes – or Veurnes – was on the evacuation route, and this is where Daisy acquired her unofficial identity bracelet. (Figure 2)

In October 1915, by which time the hard-working pair had completed a year’s service in the FFNC, Daisy and Lily had moved on to a contagious diseases hospital in Steenvoorde. At this facility, close to the Belgian border, Daisy added at least two more pieces of trench art to her collection.

One of the pieces she acquired at Steenvoorde was a plate etched with a typical Flanders’ scene. (Figure 3) The other was a cup – a memento of the hospital and perhaps a gift from a grateful patient. It has the name of a popular cherry liqueur, Guignolet, etched on the handle. Perhaps it was meant for sipping something stronger than tea! (Figure 4). Daisy’s other pieces of trench art – rings and rifle cartridges fashioned into pens – are somewhat harder to pin down to a specific time and place. (Figure 5)

Figure 5. 'Trench art' pens made from cartridge cases, collected by Daisy Hitchcock, 1915-1919. Maker unknown. Gift of Barry Hitchcock, 2011. Te Papa (GH021523 and GH021524)

At the end of January 1916, Daisy and Lily escaped Steenvorde, and the cold bleak winter, by taking a ‘well-deserved sunny holiday at Nice’.9 However, their move to the Riviera had a more serious objective besides simply basking in ‘hot sun from 9-4’.10 Lily had fallen ill and needed a warmer climate to recuperate.

Daisy informed her mother that Lily had succumbed to ‘that old bronchitis trouble’. But this was more than a pesky chest infection, and Daisy confessed that she was ‘[f]rankly… much worried’ about her friend.11 Her concern was well founded. They soon discovered that the condition underlying Lily’s bronchitis and laryngitis was TB, which she had contracted on the hospital barge.

Even before they knew the gravity of the situation, Miss Ellison – the founder of the FFNC – had granted them leave from the corps. And while Daisy privately criticised Ellison, as ‘an irresponsible journalistic suffragette sort of female’, she was grateful for her advice and assistance, which facilitated their journey south.12

Once they had settled into their new surroundings, Daisy briefly considered heading north to Steenworde again for a stint of six to eight weeks. However, the precarious state of Lily’s health soon made her change her mind. In February 1916, Lily moved into Hopital Temporarie No 22, at Le Grande Hotel in Grasse, where Daisy dedicated herself to caring for her friend. She administered nightly gargles and inhalations, and applied linseed poultices when Lily’s illness became acute.

In 1915, Lily Lind was awarded a Croix de Guerre, a military decoration created by the French government during WWI to recognise acts of gallantry. Collection of Auckland Museum Tamaki Paenga Hira, 2001.25.609, Brent Mackrell Collection. Photographed by: Andrew Hales, photographer, digital, 29 Jul 2016, © Auckland Museum CC BY

There was no question that the two women would return to New Zealand only when Lily was strong enough to travel. Having endured a European winter, they would remain in France to avoid an antipodean one. In October 1916, Daisy and Lily resigned from the FFNC and set off on their voyage home, in the relative luxury of the New Zealand hospital ship Maheno. But they had left their departure too late. Lily died shortly after they left Columbo, on 21 November, about half-way through their journey. She was buried at sea, the twelfth New Zealand nurse to die in the war. Lily’s will had been written and witnessed, four months earlier, in mid-July, which suggests she had been prepared for the worst.

A bereft Daisy continued on to New Zealand. But the loss of her close friend, with whom she had shared so many challenging and affecting war-time experiences, did not mark the end her military nursing career. In May 1917, Daisy enlisted in the NZANS and after six months working at Trentham military camp she returned to England.

From December 1917 until May 1919, Daisy was posted to the New Zealand Expeditionary Force’s general hospitals at Brockenhurst and Codford, which were established for the exclusive treatment of New Zealand soldiers. This made for a relatively familiar atmosphere compared to the multi-national wards in which she and Lily had worked.

%20-%20Daisy%20Hitchcock.jpg)

Daisy Hitchcock (exteme left) with patients in Ward 18 decorated for Christmas, Brockenhurst (No.1 NZGH), 1917-1918. Reproduced courtesy of Barry Hitchcock

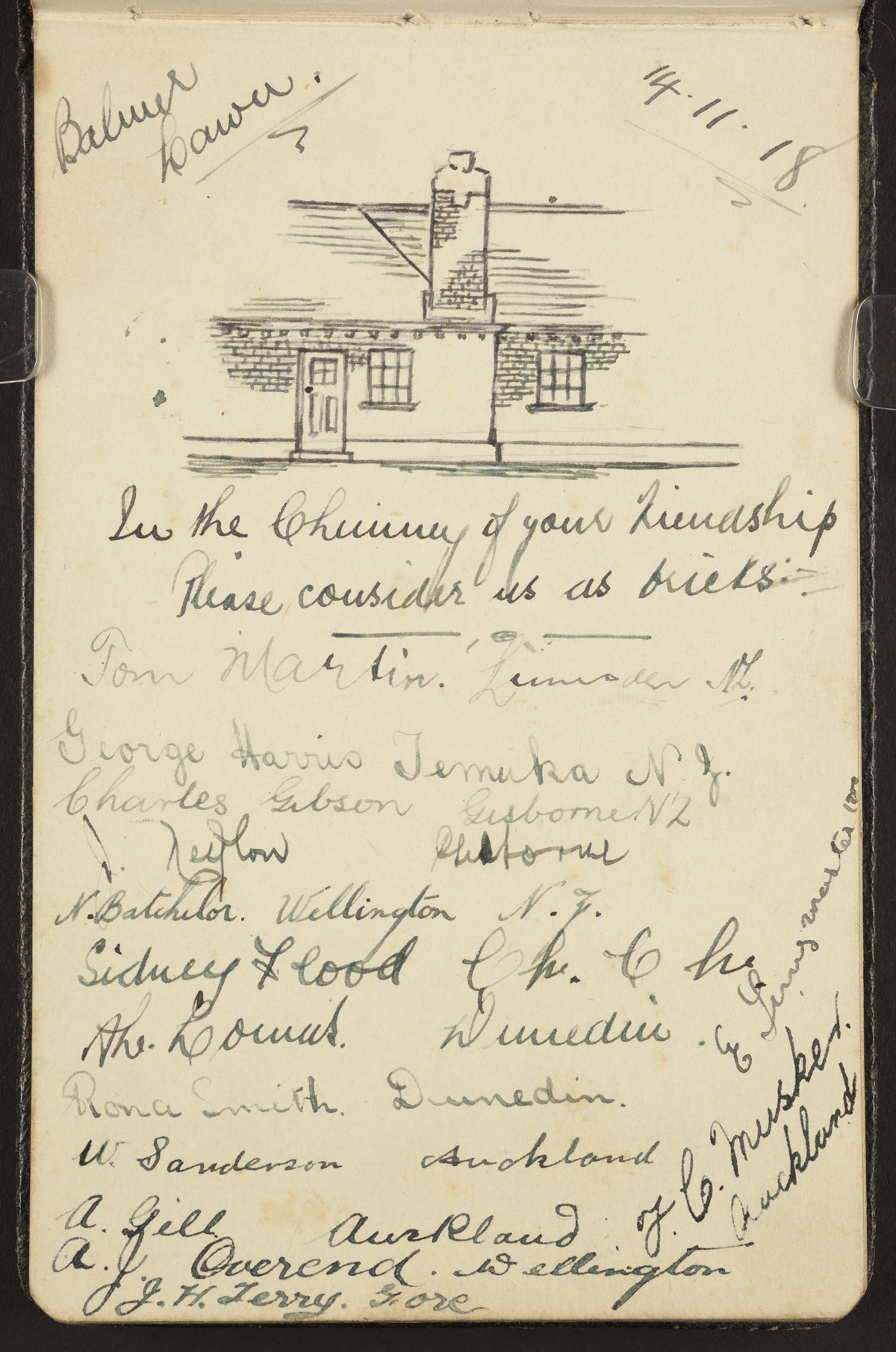

At Brockenhurst, Daisy was rostered to work at Balmer Lawn, an officers’ convalescent home where ‘the top floor [was] all nerve cases and shell shocks’.13 She continued to nurse shell-shocked men immediately after the war, at Queen Mary’s Hospital at Hamner, where she ‘proved herself most capable’.14

However, most of Daisy’s post-war professional life was dedicated to the care of infants and mothercraft training, according to the philosophies and principles of Dr Truby King and Plunket. After a short period of specialist training in the early 1920s, Daisy took up a series of appointments as Matron at Karitane Hospitals in Auckland, Dunedin and Wellington.

Daisy was 56-years-old and retired when the unthinkable happened: another world war was declared. Again, she offered her professional services to the Allied cause. This time she was based closer to home, taking up a nursing management role with the Air Force in Rongotai, Wellington. In 1946, the award of an MBE formally recognised Daisy’s contribution to the British Empire through her military nursing.15

Daisy’s trench art, however, manifests tangibly the transnational and personal dimensions of that work. These handcrafted objects also remind us that while she and Lily were nurses in the FFNC, working in unfamiliar places and caring for many non-British nationals, they belonged to a network committed to a universal aspiration: the alleviation of suffering and preservation of life.

Daisy Hitichcock collected the autographs on this page shortly after the Armisitce was announced, from men recuperating at Balmer Lawn, Brockenhurst (No. 1 NZGH). Margaret Hitchcock's autograph album, Ref: MS-Papers-11195-09_68.tif. Alexander Turnbull library, Wellington, New Zealand

Footnotes

1. Grace Ellison, founder and first Director General of the French Flag Nursing Corps, circa 1918. See http://www.scarletfinders.co.uk/167.html, accessed 1 December 2015.

2. For the formation of the NZANS see Anna Rogers, While You’re Away: New Zealand Nurses at War 1899-1948, Auckland, 2003, chapters 3 and 4.

3. The British Journal of Nursing [BJN], 24 October 1914, p. 321.

4. At least three other New Zealand nurses served in the FFNC: Ella Cooke, Caroline Holgate, and Mary Eaddy. Eaddy’s FFNC badge is held at Waikato Museum. Beryl Rawlings may possibly have served in the corps, but further documentation needs to be seen before this can be confirmed.

5. Extracts from letters dated 1 and 26 November 1914, published in Kaitiaki: The Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand, 1 January 1915, p. 37.

6. BJN, 29 May 1915, p. 461.

7. Letter dated 11 June 1915, published in the Southland Times 30 July 1915, p. 5.

8. Letter dated 24 August 1915 published in Kaitiaki, 1 October 1915, p. 20.

9. BJN, 26 February 1916, p. 182.

10. Daisy to her mother, 13 February 1916, Letters from Margaret Hitchcock written during World War I, MS-Papers-11195-01, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand (ATL).

11. Dais to her mother, 13 February 1916, MS-Papers-11195-01, ATL.

12. Daisy to her mother, 1 February 1916, MS-Papers- 11195-01, ATL.

13. Daisy to her mother, 7 July 1918, MS-Papers-11195-01, ATL.

14. Matron Pengelly, Queen Mary Hospital to Matron-in-Chief, NZANS, 2 August 1921, Margaret Hitchcock’s personnel file, AABK 18805 W5937 146 / 0356933, Archives New Zealand, Wellington.

15. Besides Daisy’s MBE and Lily’s Croix de Guerre each woman – Lily posthumously – received the ‘Medal of French Gratitude’, a decoration awarded to civilians, in 1920. BJN, 11 September 1920, pp. 145, 146.