As we mark the end of the First World War by commemorating the 97th anniversary of Armistice Day, it is timely for us to think about the armistice the New Zealanders observed at Gallipoli.

Burying the dead during the Armstice, 24th May 1915. Courtesy of Auckland War Memorial Museum – PH-NEG-C54356

When thinking about the conditions at Gallipoli in 1915 we tend to remember tales of excessive heat, inadequate water, poor diet and constant danger from enemy fire. One of the lesser known discomforts of Gallipoli was the stench. The broiling hot days and unburied dead combined to produce a terrible odour, and also posed a dangerous health risk to the soldiers living on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

By May 1915, after a month of battle, the bodies of thousands of dead Ottomans, Australians and New Zealanders littered the narrow no-man’s-land between the two lines of trenches above Anzac Cove. The smell of these decomposing bodies meant that the front lines at Anzac had become almost uninhabitable. A burial armistice – or truce – was arranged for 24 May so that soldiers from both sides could recover and bury their dead comrades.

For that one day at Anzac Cove, life strangely altered. On 24 May 1915, there were no recorded deaths amongst the New Zealanders in the Anzac sector. The cacophony of artillery, rifle and machine gun fire ceased between the hours of 7.30 am and 4.30 pm. The peace gave many men who weren’t on duty the opportunity to relax and bathe at Anzac Cove. Others discovered the humanity of their Turkish enemies through conversation and the exchanging of cigarettes. For some of those tasked with burying the corpses in no-man’s-land, the horrors of war were amplified. What thoughts did the New Zealanders record about the events of that day?

Turkish soldiers in no-man's-land during the armistice. The flag denoted the limit that Allied troops could go. The soldier on the right carries Turkish rifles from the battlefield, and several men carry shovels for burial purposes. Image courtesy of Wairarapa Archive, Ref: 11-130/2-63.digital.

By 24 May, some of the deceased had been lying in no-man’s-land above Anzac since the landings a month before. However, the majority of the dead were the result of a major frontal attack the Ottomans had launched on Anzac trenches on 19 May. An estimated 3,000 Ottoman soldiers lay in no-man’s-land following this failed attack. The smell of the dead, wrote Private Clifford Walsh of the Auckland Infantry Battalion, ‘was just too awful to describe’. Trooper John Winter of the Wellington Mounted Rifles later recalled ‘there was no stink on this earth like it. The rotting human frame, you can’t get it out of your nostrils or the pores of your skin.’

Negotiations for the burial armistice began on 21 May when a Turkish envoy descended on Anzac waving a white flag. He was blindfolded and escorted to Army Corps Headquarters to discuss its terms. At the beginning of the ceasefire three days later, a party of 50 Ottomans met 50 Australian and New Zealand men at the southern end of the front line. Each man wore a Red Crescent/Red Cross armband, and held a short stake to the top of which was tied a piece of white calico. The parties marched through no-man’s-land, forming a demarcation line as they went along. It was intended that each side would identify and bury their own dead – if they happened to lie on the enemy’s side of the demarcation line the burial parties were to bring the body to the centre for the opposing side to bury.

Christchurch surgeon Percival Fenwick, Deputy Assistant Director of Medical Services of the New Zealand and Australian Division at Gallipoli, was amongst the demarcation party. His diary entry for 24 May – ‘the most ghastly day’ – describes what the men encountered in no-man’s-land:

A few yards climb brought us on a plateau, and a most awful sight was here. The Turkish dead lay so thick that it was almost impossible to pass without treading on the bodies. The awful destructive power of high explosive was very evident. Huge holes surrounded by circles of corpses, blown to pieces. One body was cut clean in half; the upper half I could not see, it was some distance away. One shell had apparently fallen and set fire to a bush, as a dead man lay charred to the bone. Everywhere one looked lay dead, swollen, black, hideous, and over all, a nauseating stench that nearly made one vomit.

Members of both the Australian Medical Corps and the New Zealand Medical Corps examine the carnage on the battlefield during the burial armistice. Photographed by Percival Fenwick, 24 May 1915. Image courtesy of Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira. PH-NEG-C54356.

Burial parties from each side worked furiously to bury the dead. The plan to bring the bodies to the centre line was quickly abandoned due to their decomposed state. Vic Nicholson of the Wellington Infantry Battalion remembered,

As soon as you grabbed a corpse by the arm to drag it over to a hole, the arm came off in your hand. So you just ended up by scratching a little bit of trench alongside of it, rolling it over into the trench and scraping some stuff back over the top. Nobody handled on that day was buried more than six or eight inches underground. The stench was so numbing that the incentive was to get out of it as quick as you possibly could.

John Persson, also of the Wellington Battalion, was not eager to be put on a burial fatigue – ‘a job I am not too shook on’ – but went and observed the burial parties. He noted how it was ‘a horrible sight to see your comrades lying about rotting on the battlefield and nearly all have someone anxiously waiting news of them.’ Norman Clark of the New Zealand Field Artillery was similarly reluctant to take part, but was given a shovel as a ‘reward for being curious.’ His work in no-man’s-land was ‘the most horrible and dreadful experience of my war. I lasted about an hour and a half before I flaked out and I was sick in the stomach and the head for days afterwards.’

Assisting the Ottomans were a number of German officers. Their presence caught the attention of the Anzacs, including Lieutenant-Colonel William Malone. He wrote:

I saw a German officer. I hated him at sight. His manner was most offensive. Our men were burying a line of Turks who were so decomposed that it was almost impossible to lift them and of course a line or trench had to be dug. He accused us of digging a sap. A rotten job to bury their dead and [to] then be accused of digging a sap made me wild. I told some of our chaps if he said anything more to squash a dead Turk on him. He snarled but got more civil.

Many of the New Zealanders had much kinder opinions of the Ottoman Turks they encountered during the armistice. Fenwick described his Turkish counterpart as ‘a charming gentlemen’, with whom he conversed in French. Clutha McKenzie, son of New Zealand’s High Commissioner in London, noted that ‘Our men conversed with the men of the enemy as far as limited vocabulary would allow, which isn’t far.’ Tahu Rhodes of Divisional Headquarters remembered that ‘There was no ill feeling between the Turks and our men, and at Quinn’s Post they shook hands and wished each other luck before returning to their respective trenches.’

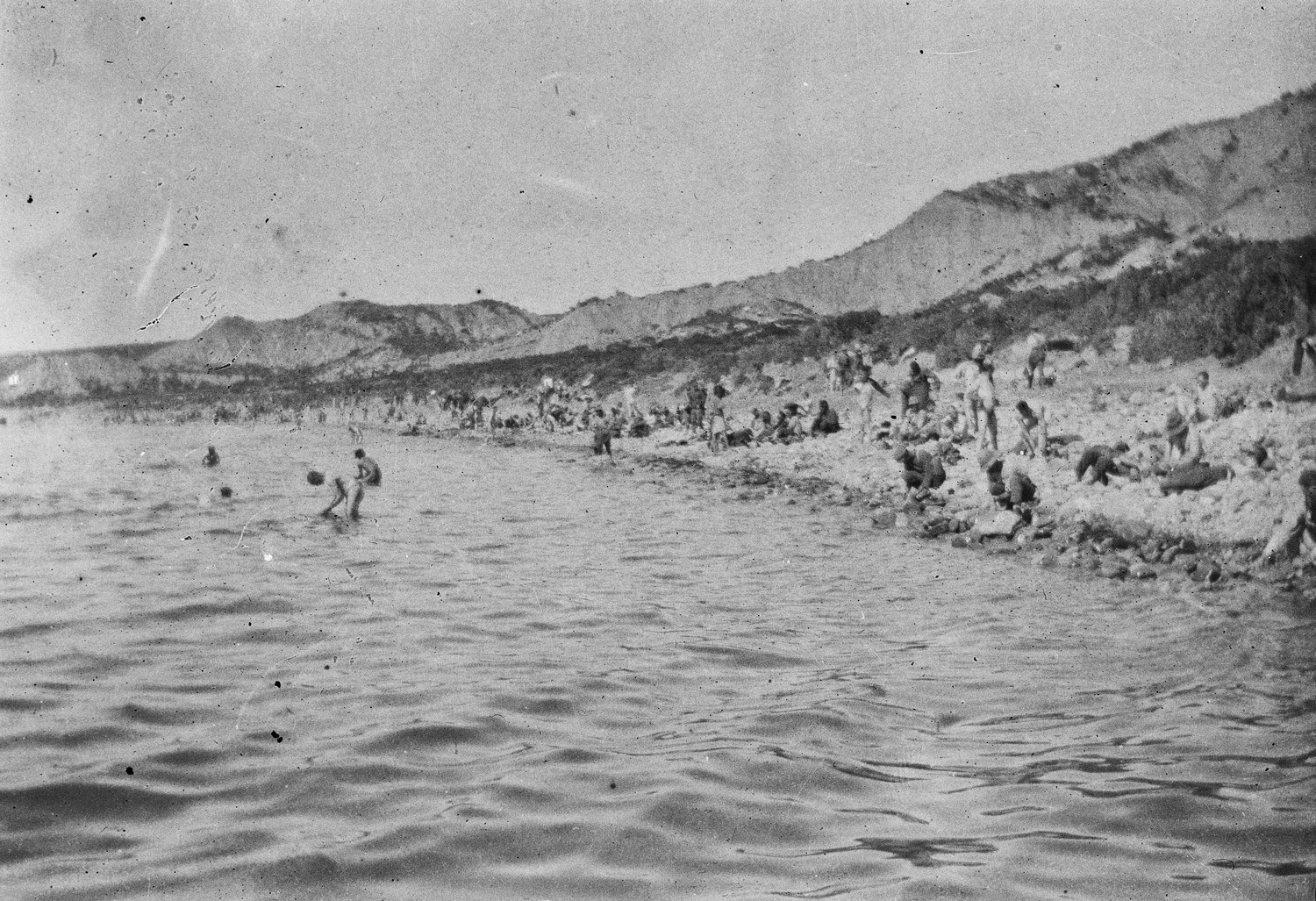

This photograph of hundreds of men bathing in the sea and delousing their clothes was likely taken during the armistice, given that the enemy usually sent showers of shrapnel over whenever large numbers took a swim. Image courtesy of Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira. PH-NEG-C61564-128.

The break in hostilities at Anzac Cove provided some relief for the soldiers not on burial duty. Kenneth Stevens of the Auckland Mounted Rifles described the day as ‘a real holiday. Not a shot or anything fired. Everything was quiet.’ Many took the opportunity to bathe in the Aegean Sea without fear of Ottoman shrapnel bursting overhead. In his semi-official history of Gallipoli, Fred Waite wrote how ‘By midday, the heat was tropical, and the Anzac beaches were crowded with the battalions from the trenches… the unique opportunity to get a safe wash was fully appreciated.’

Whether it was by getting to understand the men who were fighting in the opposing trenches, or witnessing the gruesome reality of death, the burial armistice had a profound effect on those who took part. For many it put a new perspective on war. Percival Fenwick ended his diary entry for that day with the following reflection:

I pray God I may never see such an awful sight again. I got back deadly sick… I shall certainly have eternal nightmares. If this is war, I trust N.Z. will never be fool enough to forget that to avoid war one most [must] be too strong to invite war.