After conscription was introduced in 1916, nearly 100 people were imprisoned for opposing it. Some of them would go on to have notable political careers – none more so than future prime minister Peter Fraser.

After conscription was introduced in 1916, nearly 100 people were imprisoned for opposing it. Some of them would go on to have notable political careers – none more so than 32-year-old Scotsman Peter Fraser.

Fraser had arrived in New Zealand in 1911 and, working at first as a labourer, quickly made his mark in radical socialist politics. By 1914 he was secretary-treasurer of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), which aimed to unite the political labour movement. Six ‘labour’ MPs were elected that year, two of them as SDP candidates. In August 1915 the Reform and Liberal parties formed a coalition government, with W.F. Massey continuing as prime minister; labour stayed out. As conscription became more likely, the need for labour unity became pressing. Opposition to conscription was widespread within the movement, for a variety of reasons: as an affront to liberty, as unjust if not accompanied by sweeping controls on prices and profits, on pacifist grounds, or because they felt workers had no interest in a war between empires.

Fraser and other SDP leaders now thought the party should change its name to ‘Labour’ as a move towards unity. Some also feared that the government would sponsor a pro-conscription ‘labour’ party. The New Zealand Labour Party was duly formed in July 1916, with Fraser as a foundation executive member. Like others, he campaigned against conscription after it was finally introduced in September 1916. In response, the government proclaimed regulations that defined interfering with or discouraging recruiting as sedition.

.jpg)

Wellington's imposing Terrace Gaol as it appeared circa 1910. Fraser would be imprisoned here for most of 1917, giving him time to read, think and formulate his political ideology. Photograph by Pat Fry, courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/2-058369-F.

In December 1916 many labour activists, including Fraser, were arrested. The police claimed he had told a public meeting in Wellington that ‘for the past two years and a half we have been looking at the ruling classes of Europe spreading woe, want and murder over the Continent, and it is time that the working classes… were rising up in protest’. Fraser’s defence was that he had advocated changing the law by constitutional means. The magistrate declared that while his language might have been acceptable in peacetime, it was not in wartime. Fraser was imprisoned for 12 months. During 1917, half the Labour Party’s executive was in jail.

The conditions of Fraser’s confinement in the Terrace jail, while far from pleasant, were comparatively lenient. He had abundant time to read and think, a luxury for a self-educated man. Even more important was his developing relationship with Janet Munro, whom he was to marry in 1919. Their partnership, personal and political, lasted until her death in 1945.

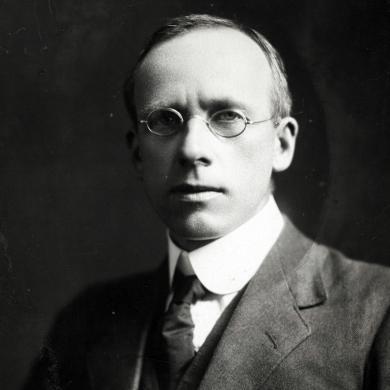

Portrait of Peter Fraser, taken by S P Andrew Ltd. in 1918. Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: PAColl-8163-51.

Released in December 1917, Fraser went back to work as a political organiser. Four by-elections during 1918 gave voters a chance to assess the government’s handling of the war effort. With Fraser as campaign manager, Labour nearly won a safe conservative seat and held Grey against a determined government attack. In October 1918, Fraser himself won Wellington Central, previously held by a left-wing Liberal, despite newspaper attacks on him as a dangerous Bolshevik (Communist). Fraser soon took a leading role in organising relief for the poorest areas of Wellington during the influenza epidemic. Labour won eight seats in the 1919 general election, thanks in part to its advocacy for those who had suffered hardship during the war – especially soldiers’ families.

Fraser remained member for Wellington Central (or renamed versions of the seat) until his death in 1950. By the end of the war he had matured both personally and politically. He refined his skills as a political organiser and developed his political thinking, not least under circumstances of enforced leisure. While not abandoning radical reform, he came to accept that the party was and should be a broad church. He began his parliamentary career at least partly because of public dissatisfaction with the coalition government. While the party did not encourage martyrdom, his spell in jail did him no harm.

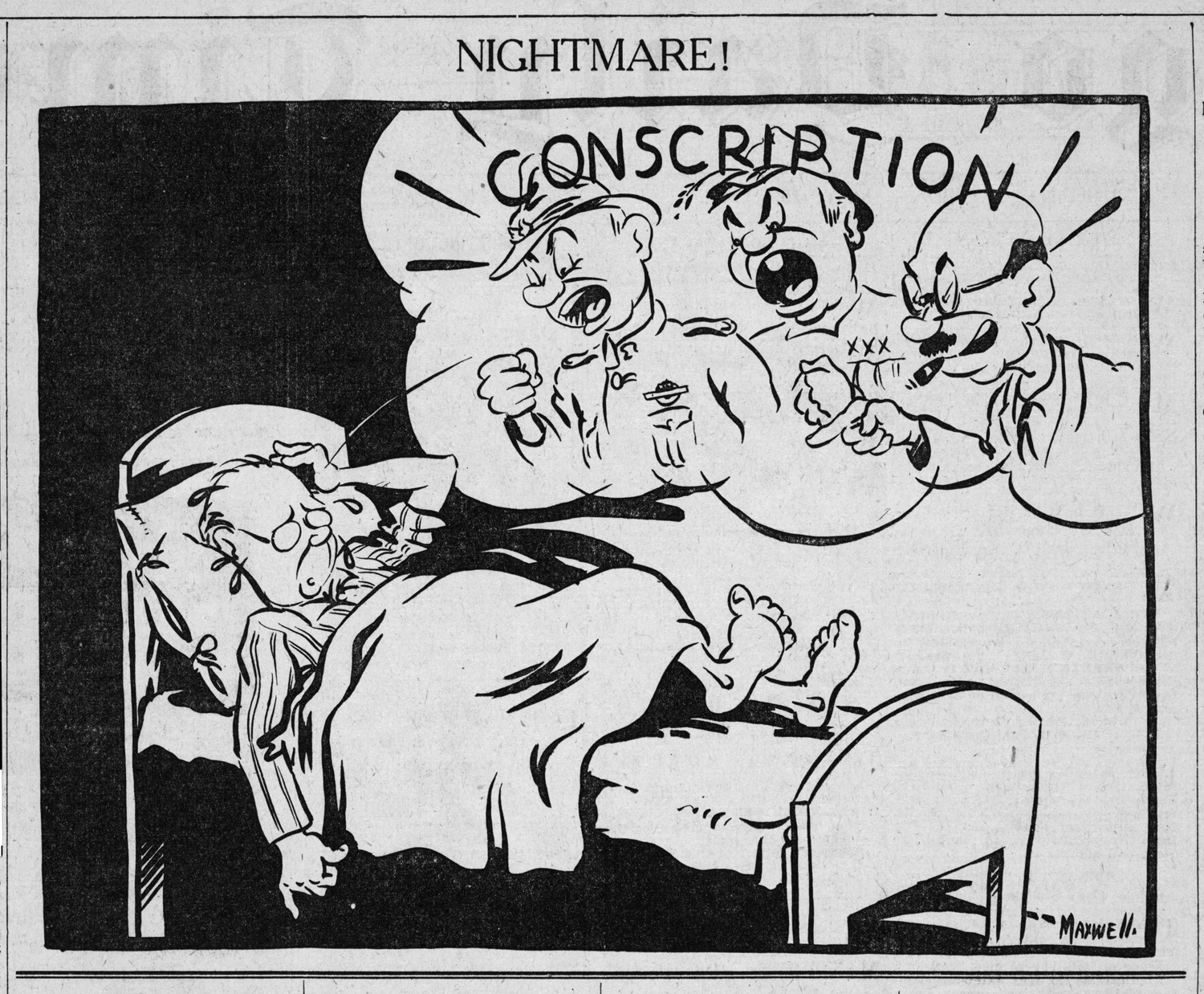

Cartoon from the Otago Daily Times, 25 May 1940, showing Fraser haunted by past soldiers and political figures for supporting conscription in the Second World War. Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: J-065-067.

As a wartime prime minister from 1940 to 1945, Fraser drew on his view of the previous war. As early as the 1920s he had argued that Labour’s commitment to internationalism and social justice would have to be balanced by a realistic analysis of the international situation. His insistence that New Zealand be treated as an equal partner in the Allied coalition, with a say in how its armed forces were used, may have reflected a belief that Massey had not stood up to the British. When the Labour government imposed conscription on Pākehā men in 1940, Fraser and his ministers ensured that this was matched by the conscription of wealth and attempts at equality of sacrifice. These measures, they believed, had been notably absent in 1916. Likewise, in supporting social justice at home and overseas, Fraser sought to avoid the disillusionments of the interwar years. However, his government’s stern treatment of pacifists was a sad irony. The Second World War may have been a war for democracy, but his government’s intolerance of dissent remains a blot on his reputation.

Jim McAloon is co-author of 'Labour: The New Zealand Labour Party 1916–2016'