Effective communications were critical to bringing order to the chaos which followed the landings at Anzac Cove. But establishing the links necessary for the passage of information between units was a difficult and frequently deadly occupation. For the New Zealanders this job fell to the men of the Divisional Signals Company and Signals Sections within the various infantry battalions. Because these roles were intended to be performed behind the front lines they were initially considered to be less risky than that of the infantryman. However, the nature of the terrain and aggressiveness of the enemy made the environment very dangerous. Runners and men using visual signalling frequently fell victim to Ottoman snipers.

A signaller with the Canterbury Battalion, Lance Sergeant Bill Leadley, recalled with great sorrow the day after the landings that “my friend Bob Wilson was killed as he was bringing a message from the firing line. We had to keep under cover all day because of the snipers.”1 Then two days later that “we have been under heavy shrapnel fire all day. We lost two Begbie lamps and a heliograph ... it was impossible to keep up communication with our various stations by semaphore because of enemy fire.”2

The use of line telegraphy and later telephone was quicker and more effective than visual signalling. But while laying telegraph lines between entrenched locations was difficult, it became even more perilous when trying to fix line breaks in daylight under artillery and machine gun fire. Acts of courage among signallers therefore became commonplace. Conducting line repairs was made even more difficult by the fact that the signallers were unarmed. It was only in early August, after two linesmen from the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Signals Troop were forced to capture a small party of Turks armed only with a pair of pliers, that they were routinely armed with revolvers.3 Perhaps the most dangerous task for linesmen was following up units after they had advanced. Sapper ‘Bunny’ Carpenter recalls the challenges of laying a line to the Otago Infantry Battalion after they had moved inland from the beach on the day of the landings:

We had to haul ourselves up with the aid of a rope for the last bit of the climb on to the top of ‘Plugge’s Plateau’, and immediately lay a wire to the Otago Battalion. The hill top was covered with scrub, and we had not gone 10 yards before the shrapnel commenced to burst around us. Seargeant [sic] Rush was hit in the lung, while not more that 3 yards from me, and rolled over on his back drumming his heels on the ground and gasping for breath. We all lay down flat, and the next shell burst so close to me that I felt the heat of the explosion on the back of my neck, and leaves and twigs from the bushes were showered over us. We left Sergeant Rush with Lieutenant Alexander, and did not see him again... Penny Michaels and I made a run for it, paying out the wire as fast as we could for 30 yards where we found the Otago Battalion, and set up our station beside Colonel Moore.4

Sergeant George Rush was replaced as Line Section Sergeant by Lance Corporal Cyril Bassett, who would become the most prominent signaller on the Gallipoli peninsular. Bassett was New Zealand’s only recipient of the Victoria Cross during the Gallipoli campaign. An honour that he later lamented when acknowledging he “was disappointed to find I was the only New Zealander to get one at Gallipoli, because hundreds of Victoria Crosses should have been awarded there.”5 Cyril Bassett’s award was largely in recognition for his bravery on the slopes of Chunuk Bair during the August offensive. However, the Victoria Cross also recognised his gallantry during an earlier attack in May. There he was one of three signallers put forward for an award, alongside Sappers Richard Hopkins and Harold Langdon.

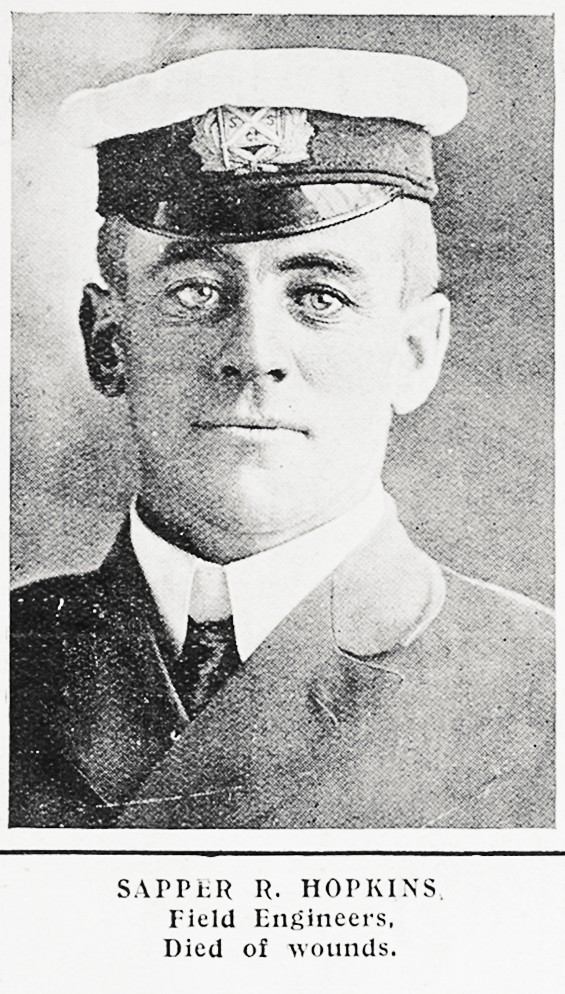

Sapper Richard Hopkins and Sapper Harold Langdon

The trio of signallers worked as linesman in support of a night-time attack by the Otago Infantry Battalion on a position close to Pope’s hill on the evening of 2 May 1915. The action was part of a larger attack on Baby 700, which was seen as critical to maintaining the ANZAC foothold at Gaba Tepe. Unfortunately, the Otagos were late following up the preparatory artillery barrage and took heavy casualties. The attack was so bloody a failure that the site of the action was subsequently referred to as ‘Dead Man’s Ridge.’ Lance Corporal Cyril Bassett twice tried to lay a line to the Otago Battalion headquarters during the night, but failed, largely due to the nature of the terrain and disorientation in the darkness. However, Sappers Richard ‘Dick’ Hopkins No. 4/594a and Harold ‘Harry’Langdon No. 4/617 set out at dawn via a different route and despite encountering heavy enemy fire succeeded in getting a line through. So impressed was the Officer Commanding the Divisional Signals Company, Captain Henry Edwards, that he recommended all three men for recognition for “good conduct.”6 While Cyril Bassett would later receive the Victoria Cross, the bravery of Dick Hopkins or Harry Langdon has never formally been acknowledged.

Dick Hopkins was particularly renowned as a brave and capable signaller. He had been a mercantile officer with the Northern Steam Ship Company in Auckland before the war. A long time member, and subsequently honorary secretary, of the Waitemata Troop of the Legion of Frontiersmen, he was strongly committed to the idea of empire and service to the King. He would have been under little or no pressure from other people to enlist as merchant navy officers were a vital occupation for the national war effort.7 Nonetheless, Dick Hopkins enlisted into the Auckland Infantry Battalion of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) aged 31, at the immediate outbreak of the War. However, he was subsequently transferred to the Divisional Signals Company on 10 October 1914, perhaps due to a degree of experience in signalling with Morse code.8

The reason for Harry Langdon’s posting to the Divisional Signals Company is not so clear. A surveyor from Wai-iti, Masterton, he had been working in Wellington prior to the War. Enlisting in October 1914 at the age of 28, Harry Langdon’s only previous military experience had been as a school cadet at Wanganui Collegiate.9 He departed New Zealand with the 2nd Reinforcements in December 1914 after minimal training and joined his unit in Egypt. From there the company sailed for Gallipoli. Harry Langdon was busy laying lines from the morning of the landings and earned a reputation for bravery alongside his companion Dick Hopkins over the following week.

On the morning of 3 May, after Cyril Basset had twice been unsuccessful trying to run a line to the Otago Infantry Battalion in the dark, Dick Hopkins and Harry Langdon managed to get it through. In the morning light they departed from Walker’s Ridge, and laid a line for 300 yards across an exposed slope to Pope’s Hill, despite the persistent threat of shrapnel, machine guns and rifle fire.10 A member of their Section would later note that the Otago Battalion had:

Advanced into a position where they were under very heavy fire. It was practically impossible and a matter of great danger to attempt to join them...Sapper H.L. Langdon and Sapper R. Hopkins, attempted the feat of effecting the communication. They succeeded in laying and joining up the line, and came back unscathed. It was a most perilous piece of work, because of the fire they were subjected to there and back.11

As a result of their actions Captain Edwards would put forward their names for special recognition. He made specific mention of Dick Hopkin’s on-going good work by advising that, “Sapper Hopkins had on several occasions repaired lines cut by the enemy’s fire at considerable risk,” and noting that Lieutenant Arthur Alexander “considers Sapper Hopkins the best sapper in his section for work requiring pluck and coolness.”12

Unfortunately, Dick Hopkins was killed within a month of this gallant action and was never decorated for his bravery. On 1 June he was sent as part of an advance party to prepare bivouacs for his Section in a new location. Lieutenant Alexander later explained that “as they were leaving the sap, by which they were to reach the new post, [he] was shot in the head,” suffering a compound fracture of the skull; “everything possible was done for him then, and he was removed to hospital almost immediately.”13 Dick Hopkins died at sea the following day and is now commemorated on the Lone Pine Memorial. Lieutenant Alexander lamented that:

The remainder of the section feel his loss very keenly, as he was immensely popular with all with whom he came in contact, and personally I know I have lost one of my most valuable men...his loss to me is serious, as he was a good soldier and a brave man, and always carried out his work cheerfully and well.14

Harry Langdon would also die as a result of his service on the Peninsula, although from a less visible enemy. The poor sanitary conditions at Anzac Cove caused him to suffer gastro enteritis and be evacuated to Lemnos Island on 23 June 1915.15 Fortunately, Harry Langdon regained his constitution at the No.2 Australian Stationary Hospital at Mudros before being ‘discharged to duty’ a fortnight later. However, the Mediterranean summer continued to contribute to an increase in sickness cases, and he was evacuated within a month with the more serious enteric fever. Taken by hospital ship to Alexandria, Harry Langdon was assessed as being “dangerously ill” by a doctor on 4 August and died the following day.16 He was subsequently buried in the Chatby Military Cemetery. A comrade would later write to his father that:

It must be a great comfort to you to know what a true and faithful soldier Harold was. He was most highly esteemed by all the signal company for his devotion to duty, this undoubted coolness and courage in danger, and his kindness of nature.17

Despite being specifically recommended for gallantry on the slopes of Pope’s Hill during the attack on Dead Man’s Ridge neither Sapper Harold Langdon or Sapper Richard Hopkins were ever formally recognised with an award. They remain unsung Kiwi heroes of the Gallipoli campaign.

Footnotes

- Walter Edmund Leadley with Jan Chamberlin ed., Shrapnel & Semaphore: A Signaller’s Diary from Gallipoli 2nd edition, Auckland, 2008, p.21.

- Ibid., p.25.

- Robert Thomas George Patrick, ‘Signal Troop’ in Official History of the New Zealand Engineers During the Great War, Norman Annabell ed., Wanganui, 1927, p.244; Laurie Barber & Cliff Lord, Swift and Sure: A History of the Royal New Zealand Corps of Signals and Army Signalling in New Zealand, Auckland, 1996, p. 48.

- Bernard Charteris Carpenter, cited in, Roy Finlayson Ellis, By Wires to Victory: Describing the work of the New Zealand Divisional Signal Company in the 1914-1918 War, Auckland, 1968, p.9.

- Cyril Bassett, quoted in, Steven Snelling, VCs of the First World War: Gallipoli, Stroud, UK, 1995, p.187; Glyn Harper & Colin Richardson, In the Face of the Enemy: The complete history of the Victoria Cross and New Zealand, Auckland, 2006, p.118.

- Henry Molesworth Edwards, ‘award recommendation’, cited in, Richard Stowers, Bloody Gallipoli: The New Zealander’s Story, Auckland, 2005, p. 418.

- Attestation form, Richard Hopkins PF; New Zealand Herald, 16 June 1915, p.9

- Medical history form, Richard Hopkins PF.

- Attestation form, Harold Leishman Langdon PF, R18058747, ANZ.

- Ellis, p. 12.

- Obituary Harold Leishman Langdon, source unknown, https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/war-memorial/ online- cenotaph/ accessed 30 August 2015; New Zealand Herald, 4 November 1915, p.4.

- Henry Molesworth Edwards, ‘award recommendation’, cited in, Stowers, p.418.

- New Zealand Herald, 17 August 1915, 8.

- Ibid.

- Casualty Form, Harold Langdon, PF.

- Ibid.

- Obituary Harold Langdon, source unknown.