Did you know that after news of the casualty figures from Gallipoli arrived in New Zealand, the Maheno was converted from a trans-Tasman passenger liner to a hospital ship in less than a month?

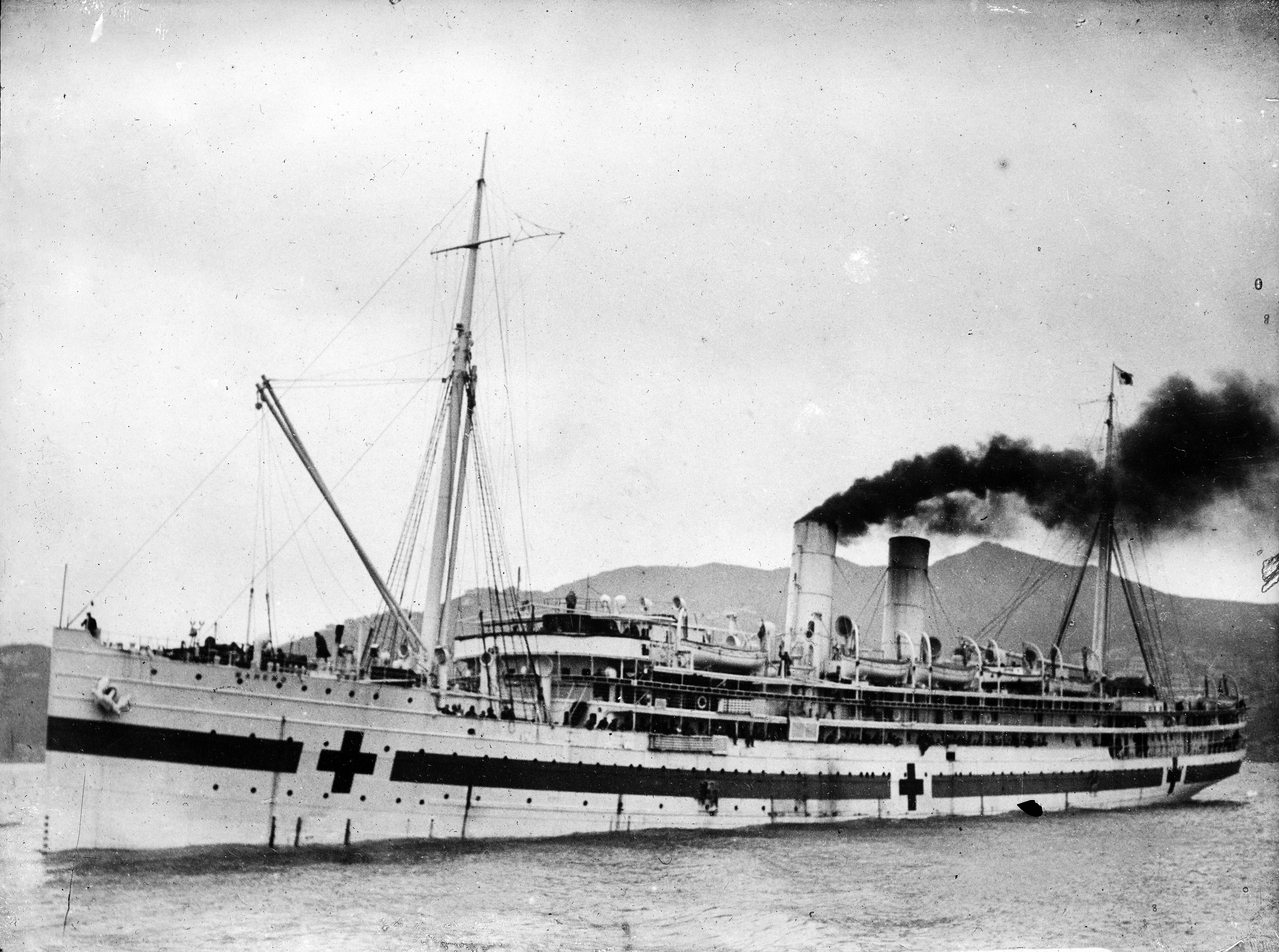

Walter Armiger Bowring, Departure of the Hospital Ship "Maheno", 1915. Courtesy of Archives New Zealand.

In late August 1915 a two-funnel ship anchored off Anzac Cove as the bloodiest push of the Gallipoli campaign got underway. The hospital ship, converted in response to the first Gallipoli casualty lists in April, wore a new colour scheme of white hull, green band and red crosses. But the Maheno’s distinctive profile would have been familiar and reassuring to many Aussie and Kiwi soldiers ashore. She had been a mainstay of the trans-Tasman trade since 1905.

Although the First World War usually evokes images of soldiers and of trenches, our merchant marine was another huge asset in a war where control of the sea really mattered. Dunedin’s Union Steam Ship Company was the Southern Hemisphere’s largest shipping line, so big that during the war its ships sent over 60% of our troops overseas, kept essential services going, and provided two hospital ships.

Why did we need hospital ships? Quite simply because of the sheer scale of the carnage. Flinging huge armies of citizen/soldiers against barbed wire, artillery and machine guns created huge casualty lists. Britain entered the war thinking that six or seven hospital ships would do but wound up running ten times that number.

The hospital ship 'Maheno' during the First World War. Dickie, John, 1869-1942: Collection of postcards, prints and negatives. Ref: 1/1-002212-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Who paid for them and how?

New Zealand’s governor, Lord Liverpool, pushed the idea of a hospital ship. The government was prepared to pay, but Liverpool suggested asking the public to contribute to providing medical equipment and soldiers’ comforts. It was a smart move. While the government paid for the big ticket items of crew wages, ship charter fees, food and fuel, ordinary New Zealanders could do their ‘bit’ to supply anything from to rolls of bandages to 12-metre-long motor launches.

The Union Company and Speight’s wrote out big cheques, but most contributions were more modest. Communities ran sports events and held special film screenings and theatrical shows. Nelson people gave a Nelson Maheno nurse £10. Ashburton kids ran a ‘Copper Week’. Throughout the country people donated clothing, books and bedding. Red Cross committees collected gifts and money and people rolled bandages by the kilometre.

While people fund-raised, Port Chalmers shipwrights stripped out most of the peacetime fittings and converted the Maheno into a state-of-the-art floating hospital. It helped that Port Chalmers was the Union Company’s engineering base. It also helped that some of Dunedin’s businesses knew how to make hospital fittings. Out went most of the passenger cabins. In came operating theatres, wards, x-ray rooms, big electric lifts to transfer patients between decks, and even a padded cell. And all this was done in less than a month!

Cover of the souvenir programme from a 'patriotic sports carnival' held at the Auckland Domain on 3 July 1915 in aid of the Auckland Hospital Ship & War Relief Fund [Ephemera relating to patriotism, fundraising for the war effort, during World War I. 1914-1918. Folder 1]. Ref: Eph-A-WAR-WI-Patriotic-1915-01-front. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

What was life like aboard these ships?

That depended on whether you were a patient or a member of the crew. The first great leveller (for all but the seamen) was finding your sea legs. The start of the voyage, through the notoriously rough Tasman and then the Great Australian Bight, quickly sorted the wheat from the chaff. Sister Ida Willis self-medicated with a blend of arrowroot, water and brandy. ‘This boat is a beggar to roll’, an orderly wrote home. Most coped but the few miserable orderlies and nurses who kept getting seasick had to take shore jobs.

People also had to get used to living cheek by jowl. The Maheno was just 120 metres long and 15 across and the complement of over 400 patients and a couple of hundred mariners and army personnel was higher than her peacetime numbers. The seamen kept their normal quarters but army personnel were sorted according to the great divide between officers and other ranks. So doctors and nurses lived better than the hard-worked army orderlies. Even so, some nurses felt that the male officers hogged the deck space.

There were other niggles as people adjusted to their new conditions. Despite the nurses having officer status, some refused to salute them. On the Maheno’s first voyage, the leader of the nurses being transported to serve in shore hospitals almost led them off in protest. After clashing with the nurses, Colonel William annoyed the ship’s captain, once cabling home for confirmation that he was in charge of the ship, not the master. Sensibly, Wellington reminded him that the captain was the master of the vessel – literally and metaphorically.

Interior of the hospital ship Maheno. Dickie, John, 1869-1942: Collection of postcards, prints and negatives. Ref: 1/1-002220-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Although the Maheno was relatively new, she had a few quirks. Designed for the cool Tasman Sea, she sometimes felt like an oven in an Indian Sea or Mediterranean summer, pure torment for the ‘black gang’, the firemen and the trimmers who fed her notoriously hungry furnaces. In 1915, shorthanded and sweating in the heat, they went on strike off Malta, earning them jail time.

But if the ship had her shortcomings for some crew, for the patients she was a real mercy ship. Sure, much of the meat and poultry was tinned, and her limited refrigerated hold space restricted supplies of fresh fruit and vegetables. But did it matter? Imagine coming aboard a big ship, with excellent food and the luxury of clean white sheets on a proper bed after enduring months of flies, dust, bully beef and cheap tinned jam in a trench. Many soldiers marvelled at just seeing proper bread and butter again. Two even dressed up as ‘walking wounded’ to board the ship, meet the master, enjoy a bath – saltwater – some smokes and decent food for a few hours before returning to the fighting.

What was life like on a busy day?

Hell is the short answer. Anzac Cove was an open anchorage. The Turks respected hospital ships, but in the absence of rear lines, jetties and all the other paraphernalia of the Western Front, wounded or sick men had to run the gauntlet across the beach and then out to the ship under fire in anything that could float. High winds or rough seas made it worse.

Once the ship had hoisted the men and their stretchers aboard, crew did a quick assessment. The dying were comforted, the seriously wounded sent below and the ‘walkers’ (lightly wounded) might have their wounds tended, be fed and passed on to another ship. On one day in August 1000 men boarded on one side of the ship and were sorted out: 400 went over the other side into lighters, while the remaining 600 were taken on a fast trip to the shore hospitals at Imbros.

Everyone lent a hand, even the off-duty sailors, who helped carry stretchers, cut bread for sandwiches and poured tea. Some even assisted in the operating theatres. For Third Officer John Duder the worst job was having to command a small boat to sink sea burials that had failed to go under.

It was even worse after the Somme in 1916. Both ships were drawn into the trans-Channel shuttle, picking up huge quantities of wounded soldiers. Crews worked killer hours and the ships sometimes carried almost twice their normal patient capacity through mine-infested waters. Exhausted patients slept back to back on deck during these dashes. When a chaplain asked a nurse what she would do if the ship struck a mine, Sister Elsye Curtis replied ‘stand by the cot cases and go down with the men.’

Of course it was not all hard graft. Port calls introduced many people to their first – and last – taste of foreign adventure. On warm, sunny days when the sea was calm, and the deck chairs came out, life could be almost idyllic – a world away from the horrors of the trenches.

By war’s end the Maheno and Marama had carried over 47,000 patients and prisoners of war.

Walter Armiger Bowring, Departure of the Hospital Ship "Maheno", 1915. Image courtesy of the National Collection of War Art, Archives New Zealand. Reference: AAAC 898 NCWA Q387.

Why do we still remember the hospital ships?

They were arguably the poster ships for New Zealand’s First World War effort. Is there an acceptable face to warfare? Probably not, but the ‘white ships’, the ‘mercy ships’ came closest to it. Brightly painted and widely reported (unlike the grey-painted troopships), they often featured in the papers.

The ships left service in the 1930s, but the Maheno refuses to fade away. She broke loose in a storm while being towed to Japan for scrapping and ran ashore on Fraser Island, where her rusting wreck remains a tourist attraction on the beach that’s now named after her. Some British visitors named their band ‘Maheno Wreck’. In 2015 pupils from the Maheno School visited on Anzac weekend, while back home Te Papa featured a large scale sectional model of the ship in its blockbuster exhibition ‘Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War’.

_IGP4364.jpg)

The wreck of the Maheno on Fraser Island, Queensland, Australia. Image courtesy of Alchemist-hp on Wikimedia Commons.