Seán Brosnahan – Curator at Toitū – recounts the story of the 100 year journey around the world of a dog tag belonging to Reinhold Fätsch, who went missing during the 1916 Battle of the Somme.

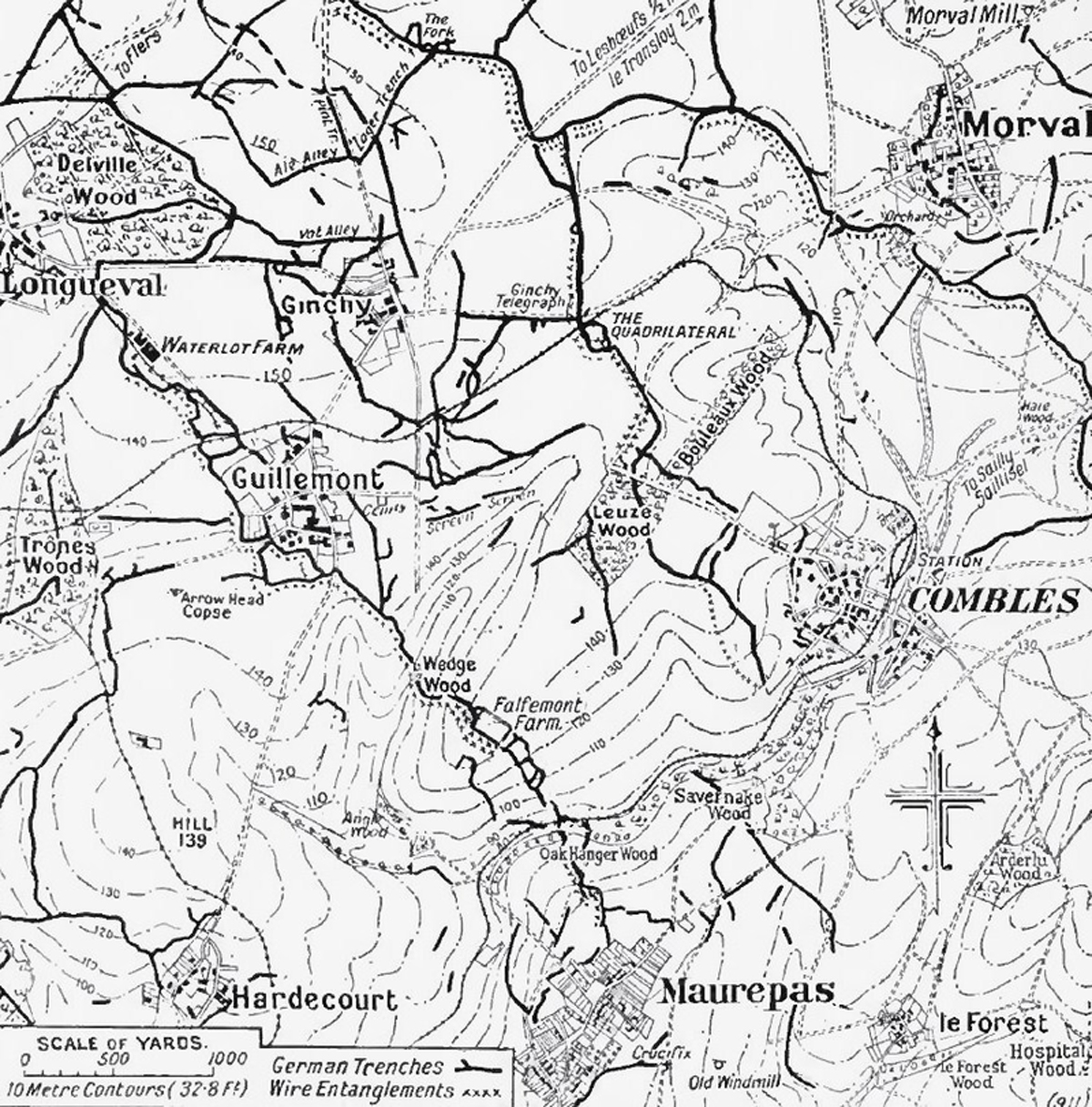

In early September 1916 the German 76 Infanterie Regiment from Hamburg was stationed in the trenches opposite Guillemont in the southern portion of the British zone of the Somme battlefield. Since the beginning of the Somme campaign on 1 July the British Fourth Army had been battering away at the German line in this sector, preparing for the next big ‘push’ forward timed to begin on 15 September. The New Zealand Division would play a key role in this attack, taking part in its first major set-piece battle on the Western Front. It would drive forward from Longueval towards Flers, on an 800-metre wide front flanked by High Wood to the northwest and Delville Wood to the northeast.

In preparation for this big push, British artillery pummelled German defensive positions from Delville Wood through Ginchy to Guillemont and Combles. Ernest Junger, serving with the 73rd Hanoverian Fusiliers at Guillemont, described the scene in mid-August.

The [trench] and the land behind was strewn with German dead, the field ahead with British. Arms and legs and heads stuck out of the slopes; in front of our holes were severed limbs and bodies, some of which had coats or tarpaulins thrown over them, to save us the sight of their disfigured faces.

Map of German positions from Longueval to Combles

Just east of Guillemont, the 76th Regiment’s 3rd Battalion was holding a trench line between Leuze Wood and The Quadrilateral position to its north. It took severe casualties in the period between 25 August and 5 September, with hundreds of men killed, wounded or taken prisoner. One of those men was 30-year-old private Reinhold Fätsch. On 16 September 1916 his name appeared in the German casualty lists alongside dozens of his comrades as “Vermisst” (Missing). Just one day earlier, the New Zealanders had surged forward from Longueval, storming German trenches and seizing acres of the corpse-strewn No Man’s Land.

Almost a hundred years later, Reinhold’s Erkennungsmarke (dog tag) turned up in Dunedin, New Zealand. In 2015, two elderly Dunedin women contacted Toitū Otago Settlers Museum about their father’s First World War effects. He had been a soldier in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, a member of the 43rd Reinforcements. These men arrived in Britain too late to take part in the fighting, their transports still at sea when the armistice was signed on 11 November 1918. Nonetheless, they did several months of service in Britain and managed to see the sights before returning to New Zealand and discharge in 1919.

Reinhold Fätsch’s dog tag

Along with his memories, the Dunedin private brought home with him Reinhold Fätsch’s dog tag. How did he get hold of it? Undoubtedly it had been traded among soldiers, passing from hand to hand as a ‘souvenir’ of the war. More important, what did its presence in Dunedin mean for Reinhold’s family? If it had been stripped from his body on the battlefield, his corpse would have remained unidentified, without a grave to visit and with no certainty for his family as to his fate. The Museum was asked to repatriate the dog tag to Germany, to Reinhold’s family if possible or, failing that, to a Hamburg Museum.

Fortunately the dog tag itself contained key information about its wearer. Reinhold was born on 14 January 1886, was a member of the 10th Company of the 76 Regiment, and his home address was 86 Eckernförderstrasse Hamburg. In an amazing coincidence this address was only a block away from where Hugh Brosnahan, son of a Toitū curator, lives in the German city. And in a second coincidence, Helen Schloo, a German intern at the Museum, also from Hamburg, had once worked on the same street. Inspired by this personal connection, the two young researchers set to work on opposite sides of the world to track Reinhold through German records.

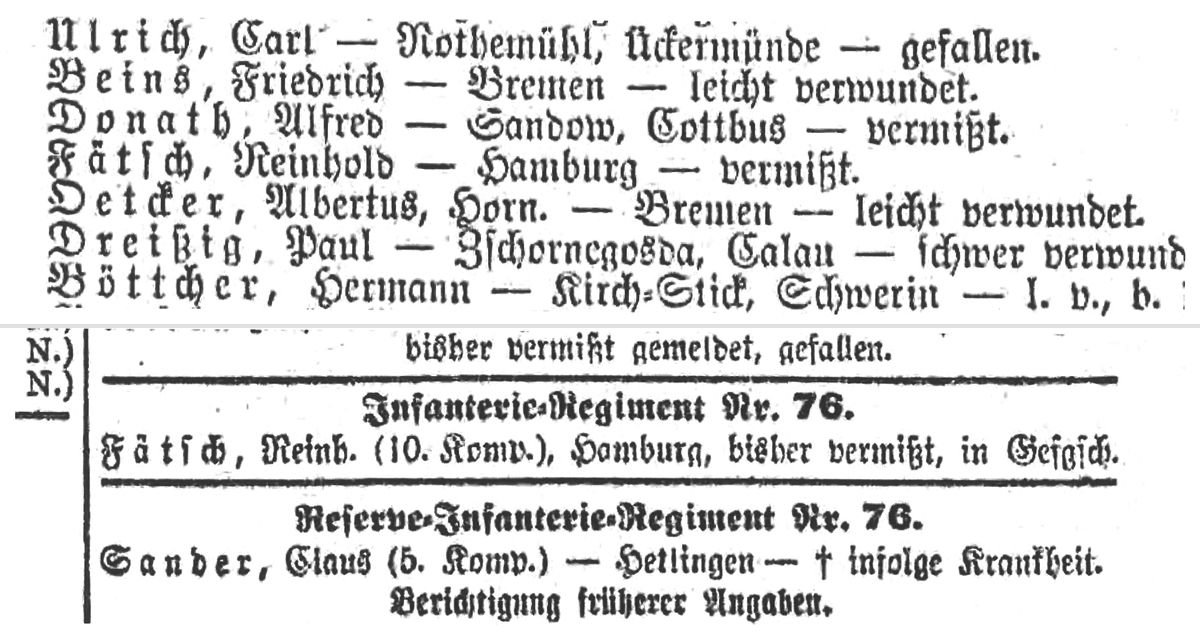

Publicity about the story brought further help from German military historian Rob Schäfer. It quickly emerged that Reinhold had not perished on the Somme after all. A second casualty notice in December 1916 updated his status: “bieber vermisst, Gefgsch.” (still missing, POW). Searching records in the Hamburg state archives, Hugh discovered that Reinhold had married Paula Achilles in Altona in 1910. Helen found his birth registration with a stamp recording his death in Hamburg in 1957. Old phone books confirmed that Reinhold had survived the war and returned home, working as an oil merchant.

Reinhold Fätsch’s casualty notices. The first (above) describes him as missing, whereas the second (below) clarifies that he is a prisoner of war.

New Zealand troops talking to German prisoners of war working on a roadside. This 1916 photograph was possibly taken during the Battle of Somme. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum. © IWM (Q 3932)

This makes Reinhold Fätsch one of the lucky ones, a survivor of the Somme and of the war. It also meant that he and Paula (she features in telephone directories up to 1976) had survived the infamous firebombing of Hamburg in the Second World War. The aptly named Operation Gomorrah, in which New Zealand airmen played a significant role, devastated the city and killed over 42,000 of its inhabitants in 1943. Whether the couple had any children remains unknown. Strict privacy rules precluded research in this area. Hamburg media outlets meanwhile showed no interest in publicising the story to flush out descendants; an indication of widespread German disinterest in First World War commemoration.

Instead, contact was made with the Altona Museum, a large regional museum in the Hamburg suburb that Reinhold and Paula called home. The museum was happy to take possession of this First World War artefact that had travelled further around the world than any other Hamburg war relic and, after a complete century, had finally made it back home. Its handover on the centennial of the New Zealand Division’s entry into the Somme campaign seems a fitting way to mark better relations between former enemies. Meanwhile, two elderly women in Dunedin were delighted to see their father’s wartime souvenir repatriated, even more satisfied that Reinhold had survived the war and returned to his wife, albeit without his identity disc.

Hugh Brosnahan and Eva Martens of the Altona Museum, Hamburg