The massive task of surveying First World War tunnels in France to help preserve their unique Kiwi character is going even more high-tech.

The massive task of surveying First World War tunnels in France to help preserve their unique Kiwi character is now going even more high-tech.

The last and perhaps most ambitious part of what has already been an incredibly ambitious University of Otago project will be undertaken by a final-year French surveying student.

Damien Houvet has joined forces with School of Surveying academics Dr Pascal Sirguey and Richard Hemi, and Otago postgraduate student Chris Page, to start turning three terabytes (3TB = 3,000 gigabytes) of surveying data into a three-dimensional virtual tour of the chalkstone tunnels under Arras in northern France.

When finished, and with the right computer hardware, individuals will be able to “move” through the tunnels 15 metres below the surface and inspect the New Zealand names, sketches and other graffiti etched into the labyrinth’s walls by soldiers in the lead-up to the Battle of Arras.

Greetings, unit emblems and names were all carved into the walls by the Allied men who occupied the tunnels beneath the French town of Arras. The words 'Kiaora NZ' are a tell-tale sign of the New Zealanders' presence.

The tunnels, which connect with historic chalk quarries, are part of a large underground military complex about 2.3km long which was built from Arras under no-man’s-land and across to the German trenches. They were secretly dug by members of the New Zealand Engineers Tunnelling Company in 1916-17 and at one stage were home to nearly 10,000 troops, with electric lights, water, kitchens and toilets, and even a light rail network.

British troops used the tunnels to make a surprise attack on the German frontline. In the Second World War they were used as air-raid shelters by locals and were seen as possible nuclear fallout shelters during the Cold War. Access is now restricted and a museum has been built over part of the complex.

Sirguey and Hemi will be in France for the 100th commemoration of the Battle of Arras during the weekend of 8-9 April. During their visit they will hand over the 3TB data set, including billions of survey points collected with a terrestrial laser scanner and animations of the tunnels, and present a one-hour lecture on 12 April which showcases the project.

Meanwhile, back at the University in Dunedin, Houvet, who arrived from the École Supérieure des Géomètres et Topographes in Le Mans in March 2017, will be researching and developing methods to get one step closer to the concept of the “virtual visit”.

Houvet says such a visit will open the tunnels to many thousands more people. A museum on top of the “Wellington” part of the complex currently allows limited access to those tunnels via an elevator and a boardwalk. But the virtual visit will eventually give anyone who wants it the ability to “walk” around much of the underground maze.

“It will be like a video game. You will be able to navigate easily in all directions in the tunnels.

“It would be difficult to create the whole virtual visit in the time I have here. But it is most important to be involved in the research and development of it, and find the best way to create virtual visits with such huge data.”

Houvet returns to France at the end of June.

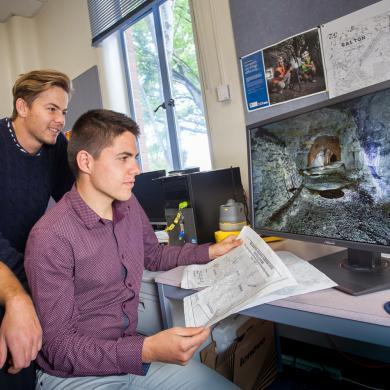

Dr Pascal Sirguey (left), Chris Page and Damien Houvet of the University of Otago School of Surveying.

Sirguey says Houvet is bringing essential knowledge to the latter stages of the LiDARRAS project, which builds on the data set that was promised to Arras.

“We didn’t offer to do the virtual environment modelling because it is not something that we are specialists with. Even though the surveying project was very big and challenging, we were confident we could handle it.

“But now we want to pursue it into the virtual modelling and the virtual visit. We want the interactivity.”

Surfaces are created from the surveyed points and then texture is added to those, with the photographed images projected back on to the surfaces, he says.

“Then you need to create a topology, which means you cannot walk through a wall, for example, and then you need to enable all that into a game engine, just like 3D games, where people can move in, turn, and you get that interactivity element through the sensors.

“There is a lot to be done and that is where our experience is limited. Our colleagues and collaborators on the project from the French national school of surveying at Le Mans have quite a bit more experience than us on this next level of surveying, this reality capture. They have done quite a bit of virtual-reality modelling.

“I don’t think by the end of Damien’s 20 weeks we will be in a position to have the entire virtual programme finished, though. This is almost something you need to task an entire company with completing,” Sirguey says.

A portrait of New Zealand troops is displayed above pick heads discovered at La Carrière Wellington.

Hemi says virtual reality is powerful because it allows for further historical interpretation of such major events.

“The thing with the Arras tunnels that really struck Pascal and I is it is a real physical New Zealand monument, with the graffiti and the names. It has a real New Zealand signature to it that, to a large extent, had been forgotten and not really well-documented. And this spatial documentation is a fantastic opportunity not only to preserve it, but to then lead on to that further interpretation of that story and history, in a very modern way.

“One of the things you can do with the virtual environment is start to add tags or keypoints, where you might be ‘walking’ along a hallway or a tunnel and there’ll be a numbered tag or box, and if you click on the box, like gaming for kids, information or a photo will come up.

“So if you walk along a tunnel and see an image or a signature, and you click on it, a really good photo of that signature might come up or a photo of the soldier and where he was from.

“This would be a huge amount of work and it is not our role because we are not historians. Having said that, we are at a university with lots of history students and academics. But we want the data to get to the point where someone else can say, ‘hey, I really want to fill in all that stuff because I’m a historian’.

“Possibly there’s also someone in Dunedin, maybe outside the university, that we may find and discuss this added-value virtual reality with, possibly someone involved in gaming.”

Sirguey says the answer to the “what’s next?” question is bringing this detailed information to the public.

“Otherwise we can keep on creating massive data that never sees the light of day.

“Capturing the data is not that difficult anymore. There is a challenge to survey it correctly, to make the data worthwhile and that is why surveyors still exist – we are not just here for pressing the buttons.

“The big question for surveyors now is, ‘how do you start making this massive data reality capture relevant?’.”