Neill Atkinson, Chief Historian at Manatū Taonga – the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, asks how the commemoration of Anzac Day has changed since it was first observed in 1916.

Detail of the first Anzac Day ceremony in Napier, 25 April 1916. Collection of Hawke's Bay Museums Trust.

It is now almost a year since Anzac Day 2015, when New Zealand and other nations marked the centenary of the ill-fated Gallipoli landings. In addition to the impressive ceremonies held on the Turkish peninsula itself, huge crowds attended events at the newly opened Pukeahu National War Memorial Park in Wellington, at Auckland War Memorial Museum and hundreds of other sites across the country, and around the world.

April this year marks the centenary of Anzac Day itself – a commemoration first held on 25 April 1916. Those first services naturally looked back to the previous year’s Gallipoli campaign, where most of New Zealand’s war dead up to that date had fallen. The nation’s attention, though, was soon to pivot to a new theatre of war. Earlier that month the New Zealand Division had arrived in France, about to embark on a brutal two-and-a-half-year struggle on the Western Front – a campaign of much greater significance and one that would claim almost five times as many New Zealand lives as Gallipoli. Over the following decades Anzac Day would come to embrace New Zealanders’ service and losses during the Second World War, Korea, Vietnam and many other conflicts – yet a century on it remains closely linked to its Gallipoli origins.

Initially Anzac Day’s status was uncertain, but in November 1920 Parliament passed legislation to introduce a full-day public holiday, which was observed for the first time in 1921. But according to Prime Minister William Massey, the aim was to create ‘a holy day rather than a holiday.’[i] The following year Anzac Day was effectively ‘Sundayised’, further cementing its sacred place in the New Zealand calendar.

Record crowds attended Anzac Day commemorations in 2015, including approximately 40,000 people at the newly opened Pukeahu National War Memorial Park in Wellington.

As the scale and intensity of the 2015 commemorations showed, the Anzac legend retains a firm grip on the Australasian imagination. Or rather, it has regained a hold that appeared to be slipping during the 1970s and early 80s, when many predicted the day was dying. This resurgence of interest in war remembrance has certainly not been unique to New Zealand; it forms part of the modern ‘memory boom’ identified by American historian Jay Winter and others. Even so, it’s clear that Anzac has a particular resonance for many New Zealanders and Australians. In these comparatively young societies, it offers a powerful foundation story and a yearned-for sense of tradition and identity, reinforced by public rituals, symbols, monuments and oratory.

During and after the First World War, the emerging Anzac legend had a more immediate purpose – it helped distressed communities make sense of the conflict’s terrible toll. As historian James Belich noted, the Great War produced a ‘cult of 18,000 Kiwi Christs … whose sacrifice simply had to have been for a noble cause.’[ii] But while it was frequently draped in religious imagery and rhetoric, Anzac was essentially a secular phenomenon. It also performed an important political function, sanctioning the repression of opposing political views – any criticism of the war was an insult to the ‘glorious dead’.

.jpg)

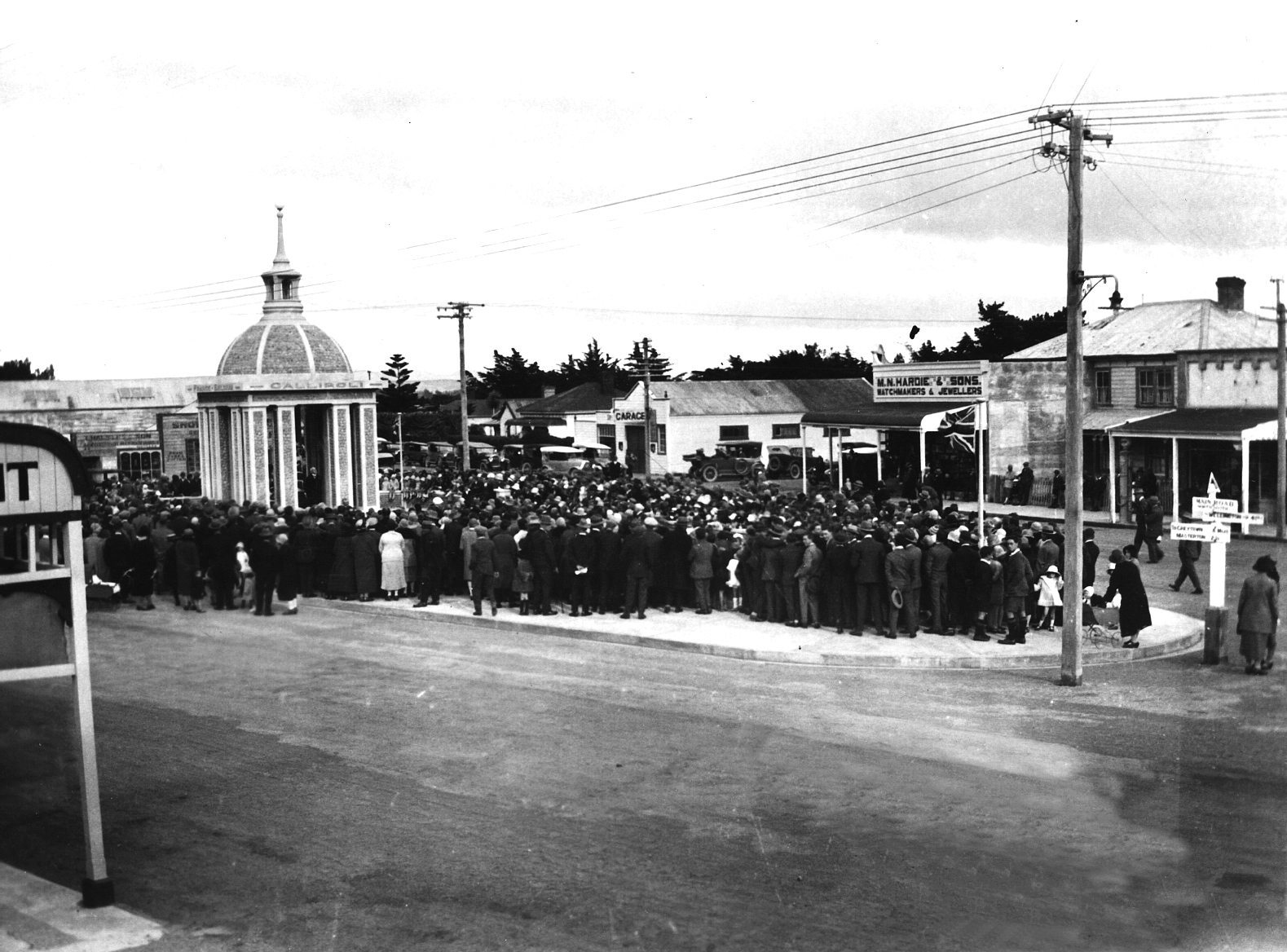

The first Anzac Day ceremony in Napier on Marine Parade, 25 April 1916. Collection of Hawke's Bay Museums Trust, Ruawharo Tā-ū-rangi, 1654, gifted by F J Griffin.

In the years after the First World War, many towns chose Anzac Day as the occasion to unveil memorials dedicated to locals who served and died at war. This image of the unveiling of the Featherston War Memorial was taken on Anzac Day 1927, and is courtesy of Wairarapa Archive, Ref: 00-270/4.

If Anzac Day was the Good Friday of this secular faith, war memorials would become its temples. The hundreds of civic monuments erected throughout the country between 1916 and the late 1930s remain the most tangible expressions of New Zealanders’ sorrow and pride in their wartime sacrifices. These monuments, which were typically called ‘fallen soldiers’ memorials’ in the early 1920s, functioned as surrogate graves for families and friends grieving without bodies, the country’s war dead being buried thousands of kilometres away (or not buried at all). Mostly funded by donations from local communities, war memorials represented a massive investment in money, time and emotional energy.

But not all veterans and bereaved families embraced Anzac Day or memorial-making. In Alison Parr’s Second World War oral history Home, Mae Carson recalled the attitude of her father, a Great War veteran:

He refused to go to Anzac Day services because he had no time for glorifying war. He was very dismissive of anything that glorified war and he became very antagonistic as far as religion went. And he said, ‘As for dying for their country, well I saw so many of them in the throes of death who were cursing their country for bringing it on.’ That was his attitude.[iii]

Such sentiments are also evident in the experiences of the legendary ‘Starkie’ (James Douglas Stark), whose memories formed the basis of Robin Hyde’s powerful wartime novel Passport to Hell (1936) and its post-war sequel Nor the Years Condemn (1938). Starkie and his mates turned up at veterans’ events for free food and booze, but seldom hid their contempt for the weasel words of politicians and parsons. ‘Cheerful civilians rose up and cleared their throats for speeches … Half-way through the dinner, Starkie said, more to the world than to the orators: “Oh, shut up. We don’t want to hear a lot of bull about the war.”’[iv]

Other, less-volatile returned men buried their anxieties beneath a cloak of silence. The writer Janet Frame’s experience was probably similar to that of many interwar children. The war was rarely spoken of in her home, only being mentioned ‘by Mum to explain why Dad was so often either sad or angry, “Your father fought in the trenches, kiddies”.’[v] In thousands of New Zealand households, there was little more to say.

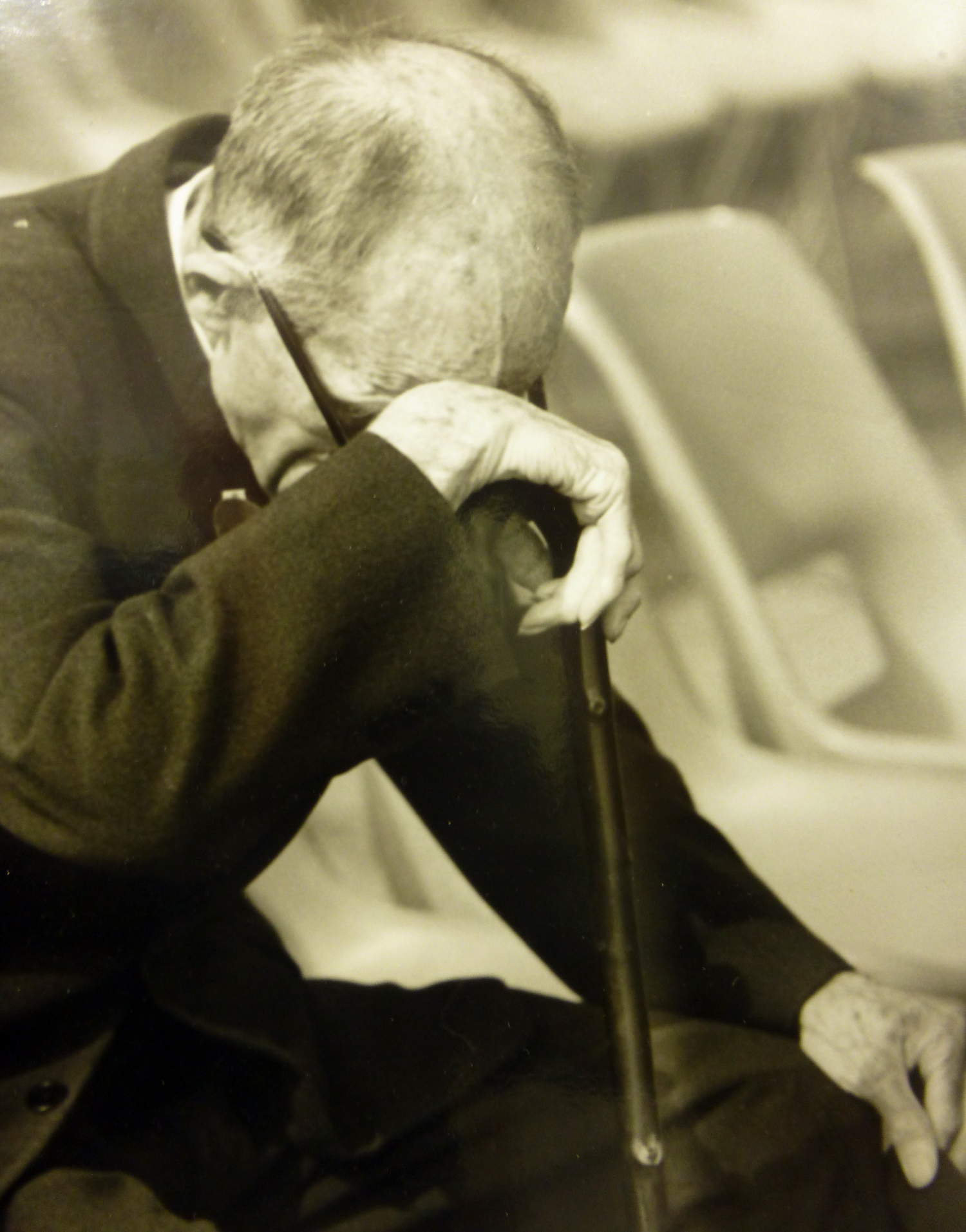

The majority of New Zealanders who served in the First World War returned home, and many of them carried physical or emotional scars for decades afterwards. This image, taken during Auckland's 1976 Anzac Day commemorations, shows the raw emotion that could resurface many years later. Image courtesy of Tauranga City Libraries.

Public commemoration could be especially difficult for the families of returned soldiers struggling with the long-term effects of wounds and war-related illnesses. Disabled veterans on crutches and in wheelchairs were prominent at Anzac Day events – even though many memorials were surrounded by inconvenient steps and platforms – but the bedridden, disfigured and seriously shell-shocked were largely invisible. Ever since 1916 the ‘backward gaze’ of Anzac has remained firmly focused on the ‘glorious dead’ – on the ever-youthful image of the fallen soldier and mass death on faraway battlefields. But not all victims of war fell in battle. Many returned home broken in body or mind, dying prematurely in the 1920s or later decades; some lost hope and took their own lives. For the families of these men, commemorative rhetoric offered cold comfort: ‘age had wearied them, and the years had condemned them.’[vi]

Remembrance can be a powerful force for unity and understanding, offering a form of collective solace and sense of belonging. It can also be a contested and divisive process that obscures nuance and distorts history. These tensions regularly surface in debates on topics that challenge the popular Anzac narrative, including wartime dissent, conscientious objection and military executions.

In 2016, as we gaze back towards that first Anzac Day, we have the opportunity not only to shift our focus from Gallipoli to the Western Front but also to recognise the rich diversity of New Zealanders’ First World War experiences. As well as those who did not return, we should remember the many more who did, and acknowledge their struggles and achievements in post-war society. We should also remember those who supported, endured or opposed the war at home. And always we should strive to interrogate the well-worn myths and legends that have shaped what, why and how we remember.