In 1919 the government began a project to build memorials halfway around the world on the very battlefields where New Zealanders had fought. Using the lantern slide photographs taken by the architect of these memorials, art historian Laura Dunham illuminates the history of New Zealand's 'battle exploit' monument construction in Turkey, France and Belgium.

The unveiling ceremony for the Gravenstafel memorial on 2 August 1924. Sir James Allen. LS.01.0102, Illumination & Commemoration, University of Canterbury.

Not all of our First World War memorials were built on New Zealand soil after the war. In 1919 the government began a project to build memorials halfway around the world on the very battlefields where New Zealanders had fought. These ‘battle exploit’ memorials commemorate the efforts of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and the New Zealand Division in five key battles that took place in Turkey, France, and Belgium.

In response to the concerns of the French and Belgian governments that their land might soon become overcrowded with memorials, the British War Office formed the Battle Exploit Memorial Committee in April 1919. Its role was to allocate battlefield memorial sites for British and Dominion forces in coordination with the Imperial War Graves Commission (I.W.G.C., now known as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) to avoid any competing claims to the same sites, or commemoration of the same units more than once. Rather than marking the actions of every British unit involved in the war, these memorials would commemorate the more significant engagements that contributed to the eventual victory.

As plans to construct a national war memorial in Wellington were temporarily shelved, in February 1920 the government set up its own battlefield memorial committee to consider decisions made by the British equivalent and make further suggestions to Cabinet. Five of the six battlefield locations New Zealand applied for were granted. By the end of the year, Cabinet had approved a budget of £5000 to construct each memorial and an architect was chosen to design and supervise their construction, Christchurch architect Samuel Hurst Seager.

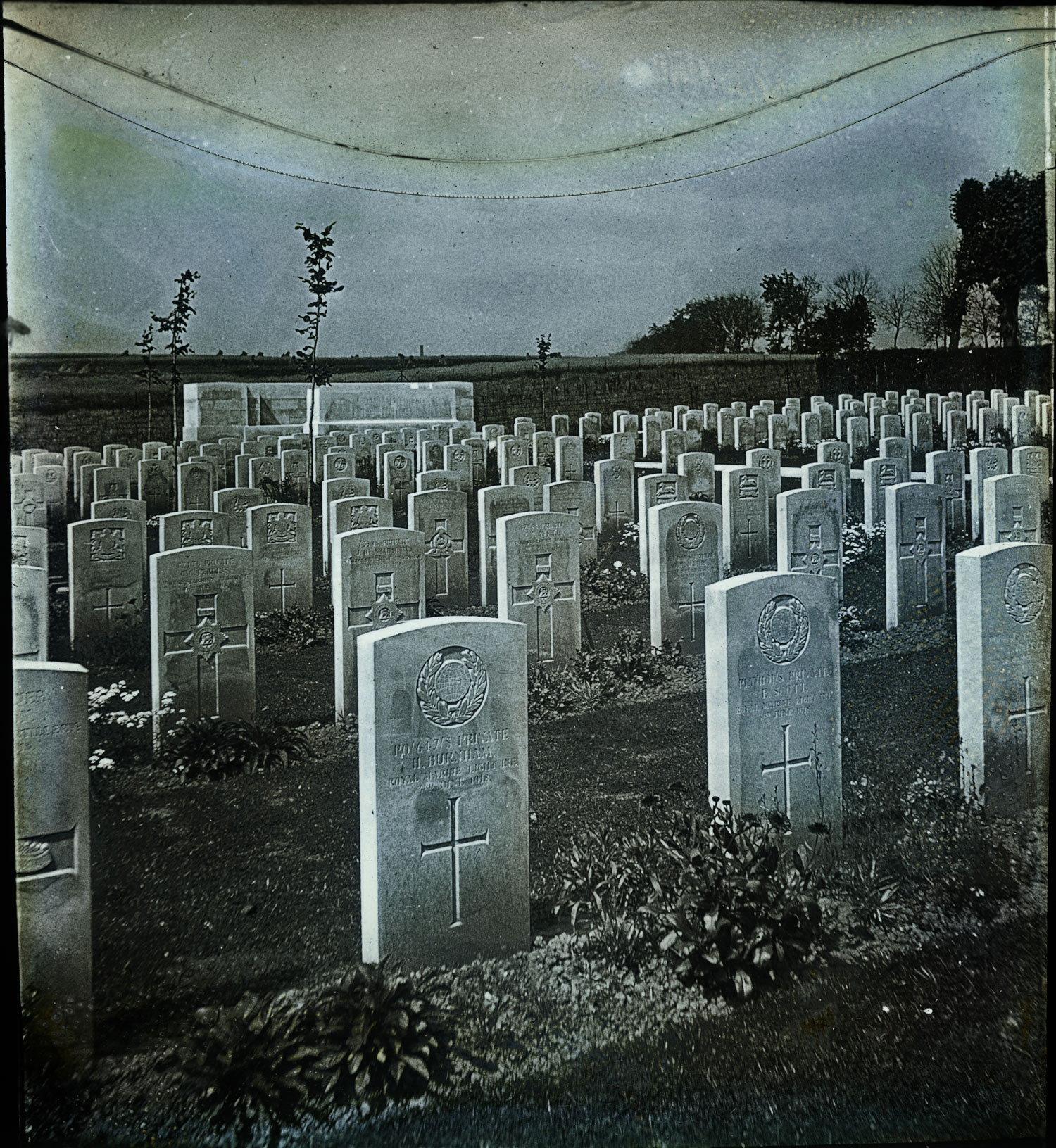

War graves in the Forceville Communal Cemetery, photographed between 1920 and 1921 by Samuel Hurst Seager, who later converted it into a lantern slide. LS.01.0109, Illumination & Commemoration, University of Canterbury.

Seager was a meticulous and highly-competent architect who had followed developments in the art and design of memorials with interest since the 1890s. In August 1920 while already in England on a research trip, he made a tour of the battlefields along the Western Front, photographing war memorials and some of the new war cemeteries constructed by the I.W.G.C. The next month he again visited the locations for the projected battle exploit memorials, this time with high commissioner Sir James Allen, who was an early supporter of Seager’s work. After Seager submitted sketches of his ideas for the memorials, he was appointed the project’s official architect.

In early 1921, Seager researched the events of each battle to help develop his ideas for the memorials. He made official inspections of the battlefields to determine where exactly the monuments should be built and how their appearance would be affected by the surrounding areas. Seager then produced preliminary design proposals for each memorial and submitted them to the government for approval.

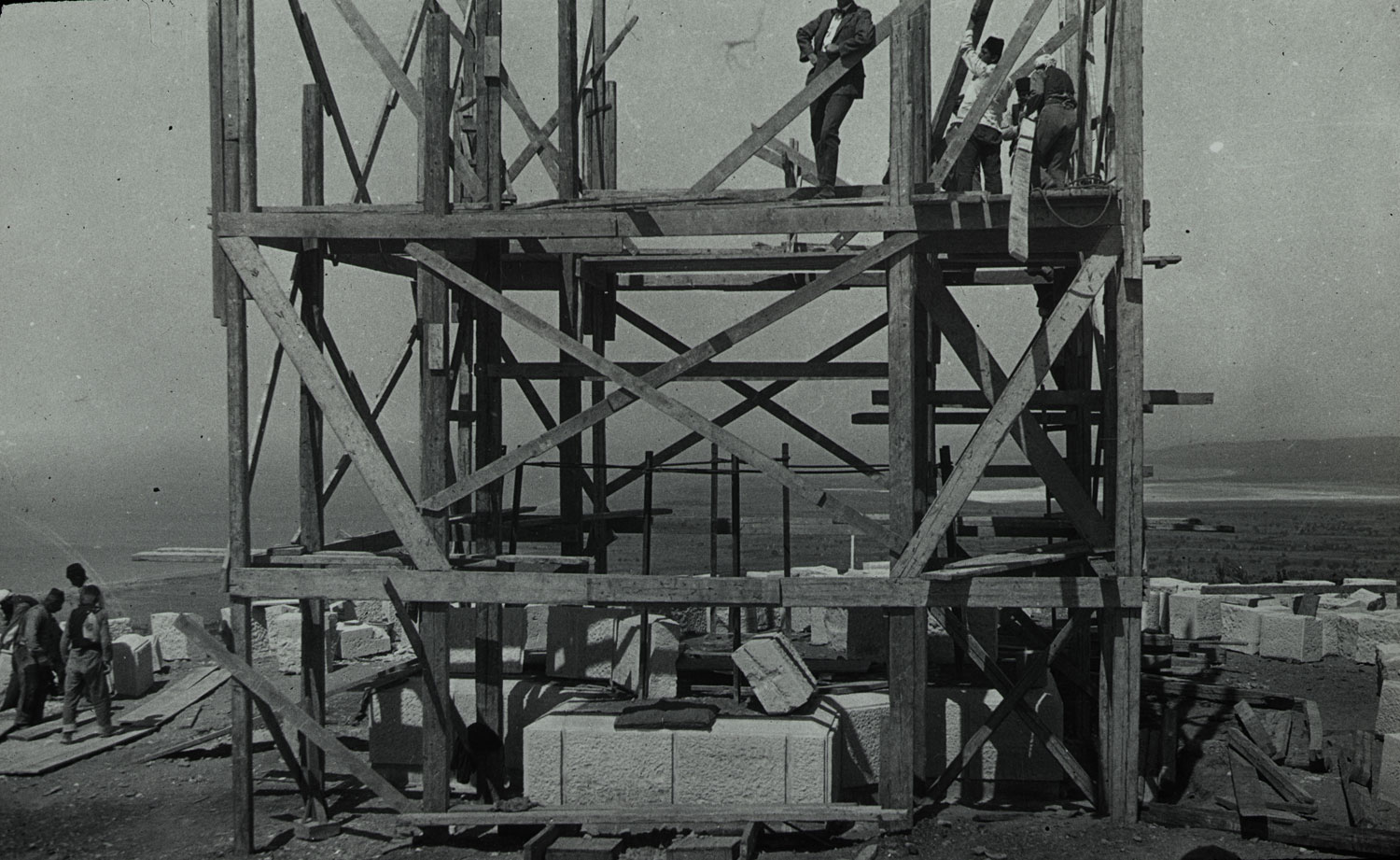

Lantern slide showing the battle exploit memorial at Chunuk Bair under construction, c.1923. LS.01.0014, Illumination & Commemoration, University of Canterbury.

.jpg)

The memorial at Chunuk Bair, completed in 1924. LS.01.0041, Illumination & Commemoration, University of Canterbury.

With the go-ahead from Cabinet, Allen entered into lengthy negotiations to acquire the sites, while Seager prepared the measured architectural drawings of each memorial. Over the course of the project, he spent five years travelling frequently between Turkey, France, and Belgium to meet with contractors, inspect materials, and monitor the progress of construction. He also travelled to a quarry in Trieste, Italy, to inspect the marble that would be used for the memorials.

Seager’s vision for the memorials not only took into account the history of the battles, but also how visitors and passers-by might interact with the monuments. When he travelled to the Dardanelles in May 1921 to inspect the isolated ridge of Chunuk Bair, Seager found that the summit was the ideal spot for a memorial as New Zealand troops had managed to secure it against constant attack during the August 1915 offensive. Aware that the location was difficult to visit, he designed a simple 18.2m high obelisk that can be seen from most parts of the Gallipoli peninsula, including the straits on either side.

The stone blocks ready for assembly for the memorial at Longueval. Part of the inscription featured on each of the memorials is visible: “From the Uttermost Ends of the Earth.” LS.01.0074, Illumination & Commemoration, University of Canterbury.

Front of the battle exploit memorial at Messines with the sculpture by A. R. Fraser. LS.01.0069, Illumination & Commemoration, University of Canterbury.

For three of the Western Front locations at Longueval, Messines, and Gravenstafel, the memorials are almost identical square obelisks. The front of each features a carved laurel wreath and a sculptural relief panel; each was designed and carved by Wellington artist Alexander R. Fraser. The panel has a circular New Zealand badge with a fern leaf over two crossed taiaha and a border pattern inspired by kōwhaiwhai design.

The gardens planted around the monuments included species indigenous to New Zealand that could cope with the cooler European climate, and suggest a conscious attempt to embed a part of ‘home’ in foreign lands. Olearias, hebes, and flax were mixed with broom, poplars, and silver beech trees, which were positioned around each site.

The centrepiece of the memorial at Le Quesnoy with wreaths, sculpted by French artist Félix-Alfred Desruelles. LS.01.0053, Illumination & Commemoration, University of Canterbury.

At Le Quesnoy, a section of the seventeenth-century wall that the New Zealand Division breached during their successful capture of the town became part of the memorial. The centrepiece is a large relief sculpture attached to the wall that shows the moment when the New Zealanders scaled the wall on November 4, 1918, watched over by a personification of Peace Victorious. Opposite the moat, below the sculpture, is an island where a viewing area was built, surrounded by native New Zealand plants in a ‘Garden of Memory’, which extended down into the empty moat.

The memorials each took less than a year to complete and were unveiled and dedicated during ceremonies, which the local communities also took part in. Longueval was the first to be finished, late in 1922, and Chunuk Bair the last, in August 1924.

The unveiling ceremony for the Gravenstafel memorial, on August 2, 1924. Sir James Allen, Samuel Hurst Seager, and General Sir Alexander Godley stand in the centre. LS.01.0102, Illumination & Commemoration, University of Canterbury.

Visitors waiting for the unveiling ceremony to begin at Chunuk Bair on May 12, 1925. LS.01.0021, Illumination & Commemoration, University of Canterbury.

When Seager returned to New Zealand in 1925 he brought back a collection of over 250 lantern slides he made from his photographs throughout the project. Using a magic lantern projector, these photographic glass plates enable images to be viewed on a larger scale, as digital projectors do today. Keen to share with New Zealanders the memorials that many were unlikely to see in person, Seager gave a series of ‘lantern lectures’ around the country, where he screened and narrated his images of the memorials.

Each memorial conveys the growing awareness of a uniquely New Zealand national identity that was, in part, shaped by the war. The project shows the government’s readiness to join in the British scheme of international commemoration, establishing permanent markers of New Zealand’s invaluable contribution on the battlefield; these would also become part of a massive boom in battlefield tourism throughout the 1920s. Today, the battle exploit memorials continue to function as an important focal point for New Zealand’s commemorations of our involvement in the Great War.