Did you know that New Zealand's most skilled Great War airman was the first person to attempt a parachute jump from a Royal Flying Corps aircraft?

Clive Collett photographed mid-air during his pioneering descent from an aircraft. Courtesy of Air Force Museum of New Zealand.

At 30 years of age, Clive Collett was one of the older New Zealanders to enter the air war when he arrived on the Western Front in March 1916. The Blenheim-born airman had worked his passage to Britain as an engineer on SS Limerick as part of the 1914 Main Body convoy. Unlike his Gallipoli-bound compatriots, however, he did not disembark at Suez but carried onto one of the many private flying schools in England.

Following a year’s worth of civilian and military aviation training, Collett served briefly on the Western Front as an airman in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), before being withdrawn from action and sent to England to undergo surgery for a long-standing injury. Upon recovery in June 1916, he was posted to the RFC’s Experimental Station at Orfordness, Suffolk. Collett was in his element in the Orfordness experimental work. His pre-war training as an electrical engineer in Wellington at William Cable & Co., his flying expertise and his devil-may-care attitude placed him in high demand. Collett’s most famous exploit, however, was a series of experimental parachute jumps from RFC aircraft.

Parachutes offered the possibility of saving an airman’s life over the front; without one, aircrew had no way of escaping a doomed machine in flight. The lack of parachutes seemed inexplicable to many, especially since it was common knowledge that observational balloonists deployed them to avoid being engulfed in flames when their hydrogen-filled perches were under attack. And when, in 1918, German airmen were seen exiting doomed machines by parachute, this added to the ire of Allied airmen.

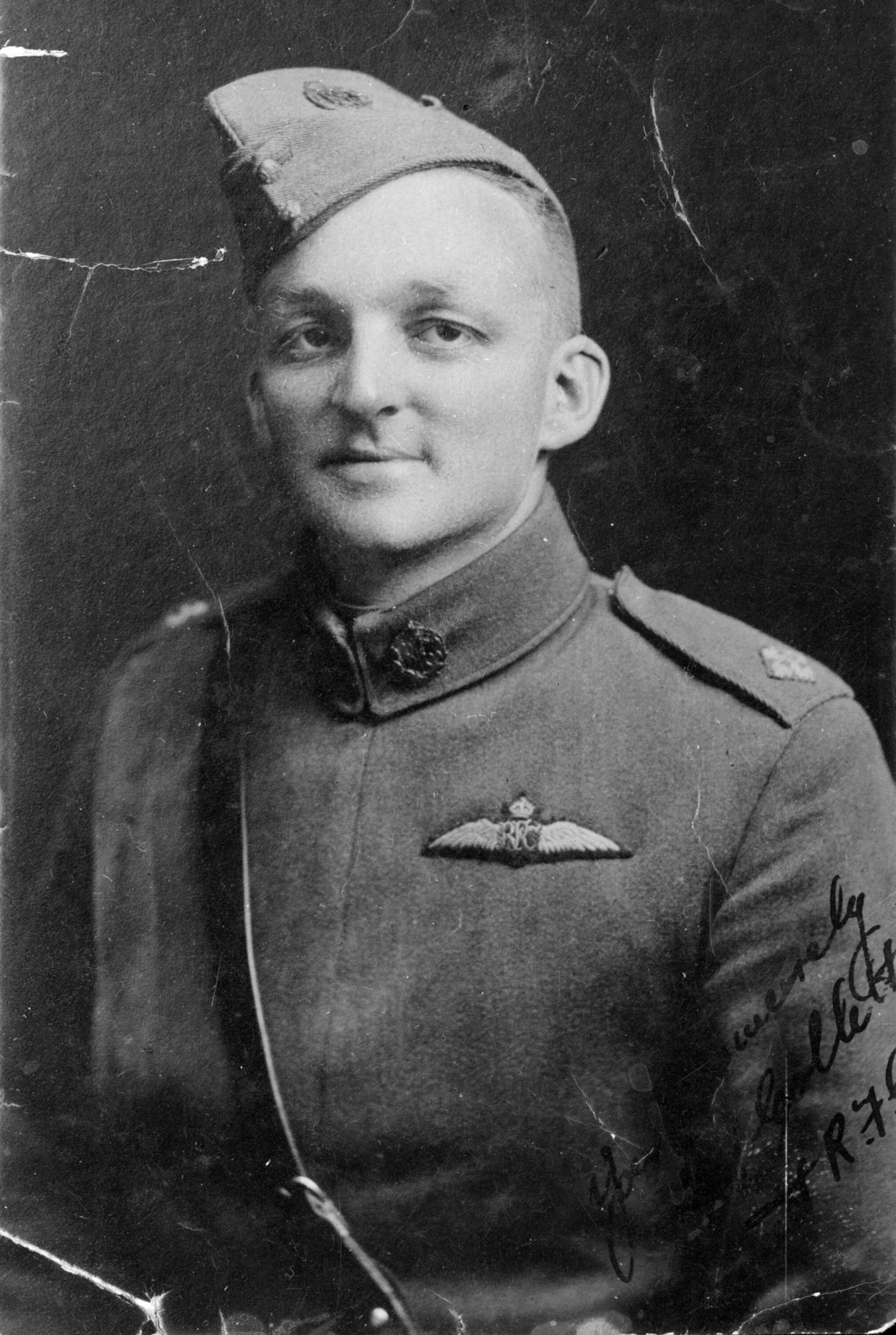

Signed portrait of Captain Clive Collett MC. Image courtesy of Air Force Museum of New Zealand.

The technology for jumping from balloons was well understood by the time the Great War arrived. However, the parachutes issued to British airship and balloonist aircrew were attached directly to the observation baskets and not carried on the backs of the crew members. When the occupant ‘bailed out’, a line attaching the balloonist to the parachute would pull the chute out of its container — in other words, a static line jump. The result was generally successful and many balloonists’ lives were saved. But these parachutes were not designed for jumping out of fast-moving aeroplanes, and their weight and bulk were difficult to accommodate in military machines. Another solution would be needed.

Englishman Everard Calthrop carried out conceptual and experimental work with parachutes for deployment in aircraft. Principally a railway engineer, Calthrop had taken up parachute development in the pre-war era when his good friend Charles Rolls, of the Rolls-Royce motor company, had been killed after losing control of his aircraft. This and a non-fatal aviation accident involving his son convinced Calthrop of the need for a reliable parachute that was suited to aircraft. His invention, marketed as the ‘Guardian Angel’, was lighter than those used by balloonists and technically more advanced. The silk chute was packed between twin metal discs in a canvas bag affixed to the aircraft’s underfuselage. The airman’s harness was attached to this by a cord. When the airman jumped free from the aircraft and the potentially entangling tail section, the parachute was pulled free and the airman floated to earth.

Clive Collett wearing his parachute harness before the test jump. Image courtesy of Air Force Museum of New Zealand.

It was this device that Clive Collett was going to test. In the days preceding his ‘live’ jump, he watched a series of airborne dummy loads being cast overboard to approximate his own upcoming effort. On 13 January 1917 the big day arrived, and the New Zealander took the rear seat in a staid and stable BE2c biplane. The pilot, Captain Robin Rowell, eased the aircraft down the runway before climbing to 600 ft. Looking down, the laconic Collett spied the station ambulance and fire tender conspicuously in attendance — vultures gathered in anticipation of a meal. ‘Much good they’ll be if my ’chute doesn’t open, but anyway it pleases the authorities,’ Collett yelled to Rowell. On the ground, a camera was tilted and running. It captured Collett awkwardly exiting the cockpit and easing himself out onto the port wing. Exposed to the elements, with the roar of the wind and the V8 engine assaulting his ears, Collett paused, then launched himself headfirst into thin air. He felt the jerk of the line as it snapped tight and the parachute was pulled from the base of the fuselage. Within seconds he had made landfall. The Guardian Angel had worked as advertised, and Collett became the first man to make a parachute descent from a RFC machine. He made a second, equally successful and drama-free jump on 21 January.

Collett photographed mid-air during his pioneering descent from an aircraft, and again once he was back on terra firma. Images courtesy of Air Force Museum of New Zealand.

In spite of Collett’s achievements, the British authorities never really took to the idea of parachutes. Further experimentations and vocal remonstrations from Calthrop were unsuccessful in persuading military aviation boards and committees to adopt the lifesaving parachute that Collett had so ably tested. Calthrop’s parachute was too heavy and cumbersome for use in the battlefield of the sky; however, it did offer the possibility of further development, had the authorities been fully persuaded of its necessity. Empire airmen could only watch and ponder in mid-1918 as German pilots escaped certain death to gently float groundwards. Where, they wondered, were their silk angels?

One of the few people in England to actually get a parachute was Collett’s sweetheart Peggy. He gave her two Guardian Angels following his test jumps; the luxurious creamy-white silk was intended for her wedding dress. When Peggy unfurled them they were sprinkled with sand from the beaches of Orfordness. She was already close to seven months pregnant with their child.

The Guardian Angels were never transformed into Peggy’s silk wedding dress – Collett died on 23 December 1917, when the German Albatros DV fighter he was flying crashed into the Firth of Forth in Scotland. Over time, Peggy, a ‘very accomplished dressmaker’ made the Guardian Angels into pretty garments for their daughter Marion and other family members.

Adam Claasen is the author of Fearless: The extraordinary untold story of New Zealand's Great War airmen

.jpg)