In a heady atmosphere of anti-German hysteria at the start of the war, German residents formerly seen as friends were now labelled the ‘enemy in our midst’. In this article historian Andrew Francis looks at the treatment of Germans in New Zealand during the First World War.

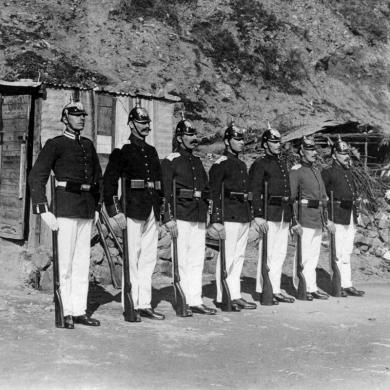

Detail of image of German internees on Somes Island. Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/2-112287-F: https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22340533

Caught up in the wave of patriotic activity at the beginning of the First World War were New Zealand’s German communities. German settlers started arriving in New Zealand as early as 1843 and became as much part of the social and economic fabric as their British counterparts. Over time, healthy relations developed between the communities. Despite this, the declaration of war forced a reassessment of British New Zealanders’ loyalties, traditions and cultural heritage. In a heady atmosphere of anti-German hysteria stirred up by newspapers editors and ‘patriotic’ societies, German residents formerly seen as friends were now labelled the ‘enemy in our midst’ and treated with growing suspicion and animosity.

Internment

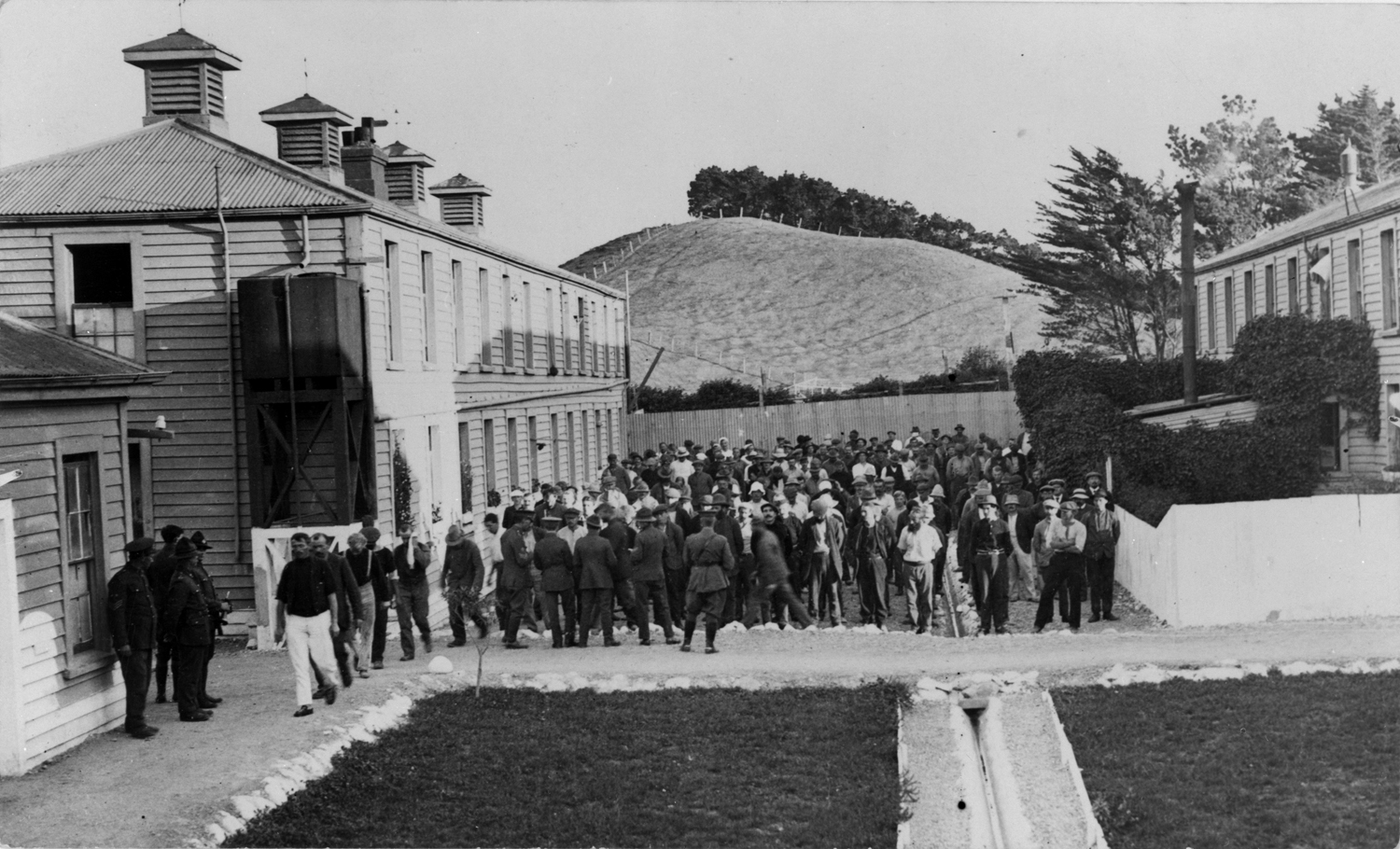

One of the government’s first security measures was to introduce internment for German military reservists who found themselves in or near to New Zealand when war started; senior figures in the German colonial administration of Sāmoa; and a number of residents deemed dangerous to home security or hostile to the dominion’s war effort. Somes Island in Wellington Harbour and Motuihe Island in the Hauraki Gulf were given over to the Defence Department and, for the duration of the war, they became New Zealand’s main two internment camps. Somes Island housed approximately 500 predominantly working class internees and prisoners of war during the four-year conflict, while Motuihe was home to around 70 Germans, mostly members of the former colonial administration in Sāmoa.

The two camps operated in stark contrast to one another. On Somes not only was the weather less pleasant than on Motuihe, but the regime instilled by the camp commandant, Major Dugald Matheson, was far harsher. Accounts of regular beatings, verbal abuse, humiliation and poor quality rations forced the government in 1918 to undertake a Royal Commission into alleged ill treatment on the island. Though the camp authorities were cleared of any wrongdoing, the report made clear that a great deal of animosity and bitterness had developed between the two communities, largely due to the regular drunkenness and misbehaviour of the guards.

German prisoners of war on Somes Island. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, Ref: 1/2-112282-F.

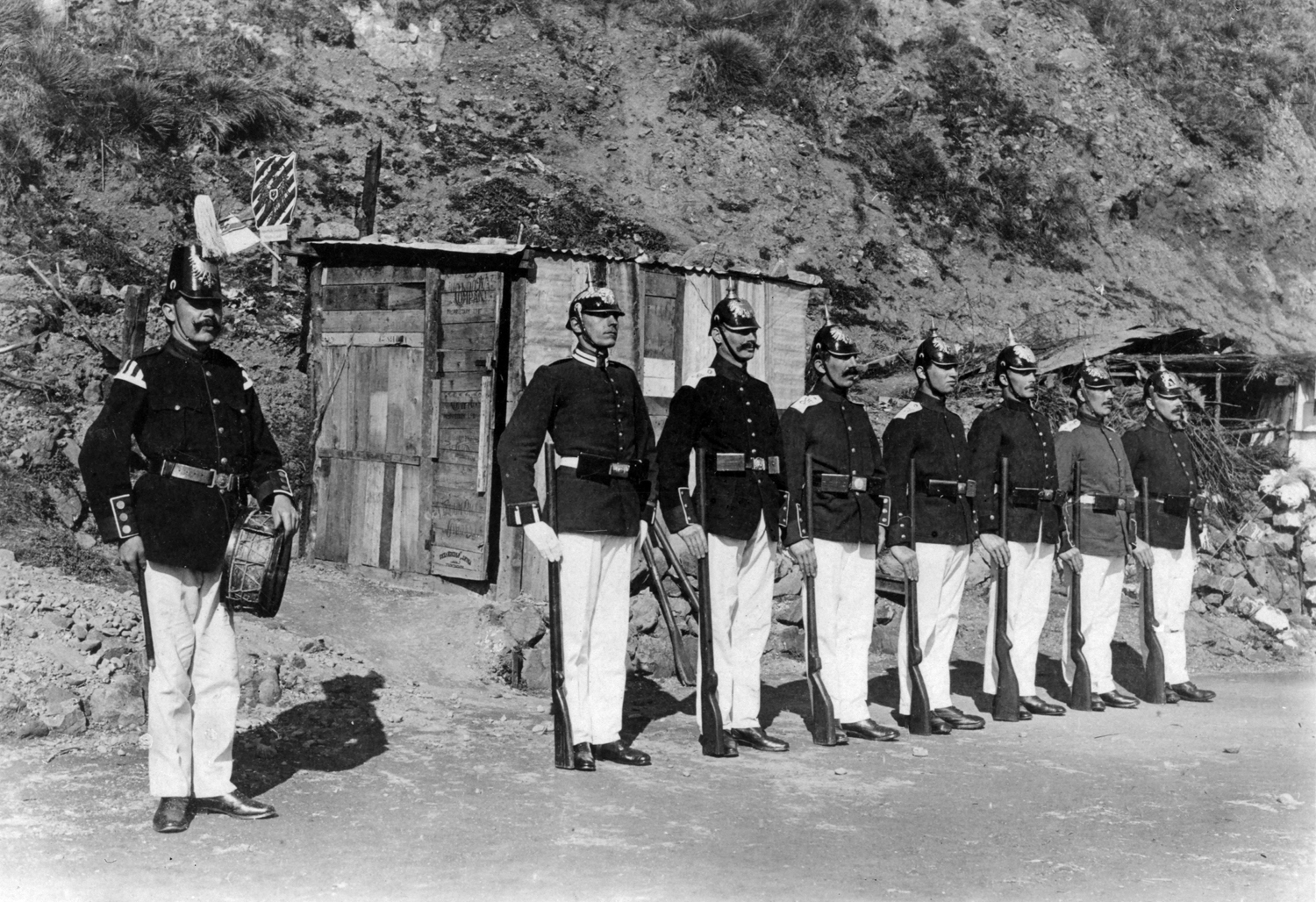

A row of German internees, in military uniform, on Somes Island during the First World War. The uniforms were made by the internees. Photographer unidentified. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, Ref: 1/2-112287-F.

Life on Motuihe was markedly different: the prisoners there had quality food rations; access to alcohol; and weather suited to men whose professional careers had been spent in the tropical climate of Germany’s overseas empire. Further, they enjoyed easy access to Auckland courtesy of camp commandant, Lt-Col Turner and his launch, the Pearl. Prisoners included the former Governor of Sāmoa and a number of other civil servants and businessmen.

Few military personnel were housed at Motuihe though one notable resident was Count Felix von Luckner. Von Luckner, aboard his raider, the Seeadler, had menaced the Royal Navy in the Pacific by seizing and destroying a number of British ships. After being captured in 1917 he was sent to Motuihe where he immediately plotted his escape. With a hastily assembled new crew he made an escape on Turner’s launch with the intention of recapturing Samoa for Germany. They were at large for eight days, long enough to cause considerable public, press and political anxiety and had travelled 1,000 kilometres north before being captured and returned to Motuihe.

The effect of the sinking of the Lusitania

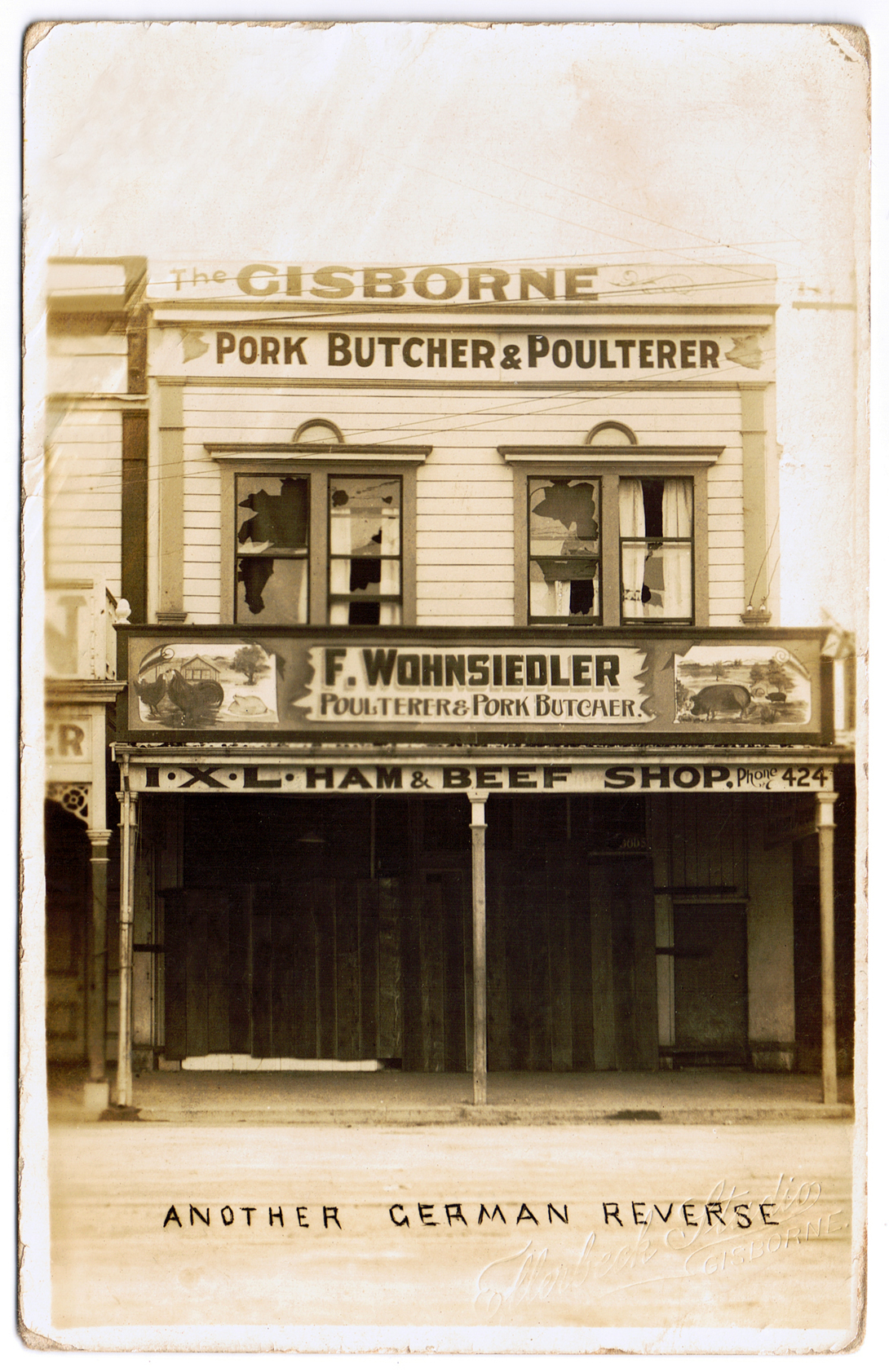

The sinking of the passenger liner RMS Lusitania off the southern coast of Ireland in May 1915 was the catalyst for the most vociferous anti-German violence, not just in New Zealand, but elsewhere within the British Empire. The loss of almost 1,200 civilian lives was regarded as a barbarous act by a nation whose reputation for brutality was growing each day. The sinking sparked further calls for the wholesale internment of all Germans resident in New Zealand. Supposed ‘German-owned’ businesses in Whanganui were attacked including Conrad Heinold’s butchery business, the Bristol Piano Company (which had recently changed its name from the Dresden Piano Company) and Hallenstein’s clothing store.

The Lusitania’s sinking occurred just as the first news was filtering back of New Zealand deaths on Gallipoli, and within days of the publication in England of the Bryce Report, which outlined alleged atrocities committed by the German military in neutral Belgium. Though the report was later revealed to be factually incorrect, its propaganda value, just as with the sinking of the Lusitania, hardened the New Zealand public’s attitudes towards Germans resident within their communities.

Newspaper reports of German atrocities in Europe helped fuel anti-German sentiments in New Zealand, and many expressed this xenophobia by targeting businesses owned by German residents. This image shows the aftermath of an attack on Friedrich Wohnsiedler's pork butchery shop in Gisborne on New Year's Eve 1914-15, when members of a reported crowd of 2,000 people threw stones and bottles at the shop's windows. Postcard courtesy of Glenn Reddiex, author of 'Just to let you know I'm still alive'.

The von Zedlitz Affair

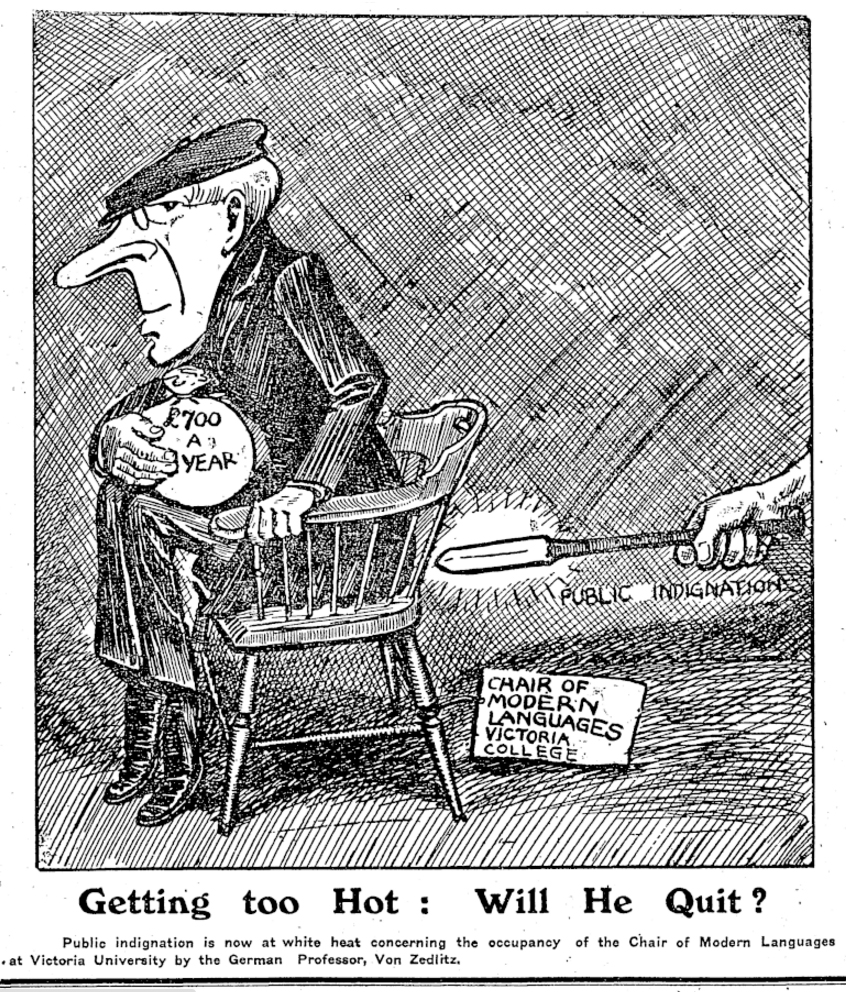

George von Zedlitz, the German-born Professor of Modern Languages at Wellington’s Victoria College (now Victoria University of Wellington (VUW)), had resided in New Zealand since 1901. When war was declared, legislation was enacted that dismissed many German residents from their posts, though von Zedlitz was spared this. A small number of politicians, supported by populist newspapers, questioned why this was so when other non-naturalized residents in similar positions of public office were not only losing their jobs but, in some cases, were also being interned. The von Zedlitz affair sparked considerable public, press and parliamentary debate. With anti-German protests mounting, the government introduced the Alien Enemy Teachers’ Act in October 1915, which removed him from his post. The legislation is significant in that it was introduced with the sole purpose of removing one person – von Zedlitz – from their post.

Professor George von Zedlitz sits uneasily on a chair clutching a bag containing £700 – his annual salary – while a red-hot poker of ‘public indignation’ draws ever closer. Cartoon published in the New Zealand Truth, 28 August 1915.

Support for ‘enemy aliens’

There was, however, regular support from British New Zealanders who felt German residents were being unfairly treated. Letters published in newspapers stated that Germans in New Zealand should be judged by their actions not by the acts being committed by the German military in Europe; the government regularly acknowledged that the war had placed ‘enemy’ residents in a difficult position and, unless they committed offences or behaved in a way hostile to the war effort, they should be free to go about their business unharmed. Locals in Wellington raised the funds to have replaced windows smashed at the German consular building following a night of disturbances in 1914; and Charitable Aid Boards supported families suffering from financial hardship whose main breadwinner was interned: a scheme which the government subsidized.

Conclusion

On 11 November 1918, the Armistice was signed between the Allies and Germany, bringing about an unofficial end to hostilities. Celebrations in many areas of New Zealand were muted as they coincided with the influenza pandemic which swept through with devastating consequences claiming 8,600 lives. The German prisoners were transferred to Featherston Camp or Devonport Barracks where they were held prior to their release or, in the case of 410 internees and prisoners of war, their repatriation to Germany in May 1919. A number of German deportees, however, had British-born wives who were faced with the difficult decision whether to remain in New Zealand or accompany their husbands back to war-ravaged Germany.

.jpg)

The SS Willochra, transporting hundreds of German internees, stopped at Sydney before sailing on to Plymouth. Cartoon from the New Zealand Free Lance, 28 May 1919.

German-born residents who remained in New Zealand were subject to war regulations until October 1920. Those German-born residents who had purchased land during the war were liable to have it seized by the government. The hostility shown towards Germans during the war, however, quickly subsided as the country tried to return to normality. Von Zedlitz never regained his post at Victoria University College, instead establishing a private tutorial school; however, the current Modern Languages building at VUW is named in his honour.

Like most imperial societies in the first months of war, New Zealand’s treatment of its German-born and German-descent communities was fair, though events like the sinking of the Lusitania and stories of German military attacks on innocent civilians overseas encouraged a small number of anti-German MPs and an increasingly belligerent popular press to campaign for tighter controls against enemy ‘aliens’. In general, however, there were lengthy periods in which relations between the communities were incident-free. Prime Minister William Massey and his government largely resisted public demands for greater restrictions of enemy aliens, relying instead on a sense of justice and fair play.