Te Papa curator and historian Kirstie Ross uncovers a collection of photographic portraits of First World War soldiers – a forgotten building block in the evolution of New Zealand’s war remembrance.

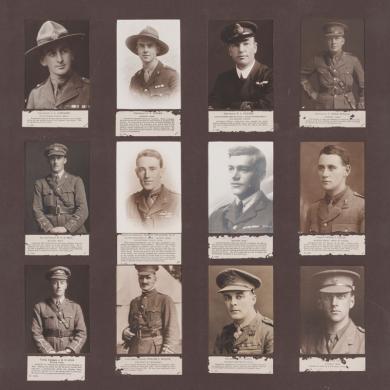

Detail from one of the boards displaying portraits of Great War medal winners. AALZ 902 61, Archives New Zealand.

In 1917, well before most of New Zealand’s First World War memorials were built, Dr Allan Thomson, the Director of the Dominion Museum, implemented an ambitious commemorative scheme on behalf of the nation. This scheme involved a contemporary collecting strategy and the construction of a war museum displaying these new acquisitions alongside official war trophies.[i]

Two important factors underpinning the initiative were Thomson’s growing interest in social history and his fear that valuable evidence of the Great War would be lost to future generations – a situation he was facing with material associated with the New Zealand Wars. As Thomson noted in March 1917, it was practical to collect history as it was happening:

‘The heroes of today will be the veterans of to-morrow and there is no reason why their writings and doings should not be collected while the fighting is going on, instead of leaving it to a future generation to send out a search party … to discover and fill in the blanks in the past history of the Dominion.’[ii]

The acquisition and display of photographic portraits of New Zealanders awarded medals for gallantry was an important – and ultimately the most successful – component of Thomson’s war-related collecting. (The national war museum did not eventuate.) Yet this collection held by Archives New Zealand and available online is a forgotten building block in the evolution of New Zealand’s culture of war remembrance – one which deserves our closer attention.[iii]

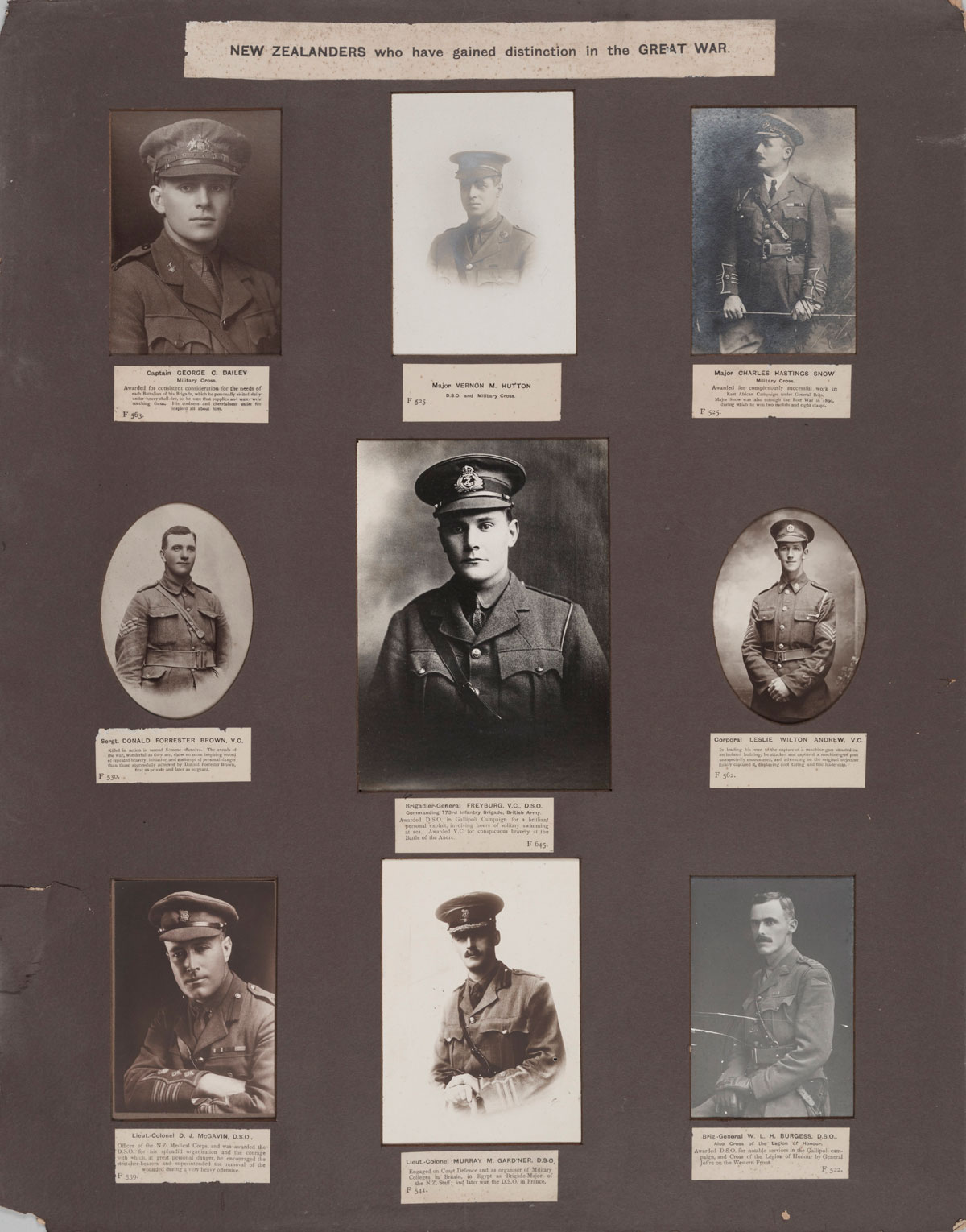

Portraits of medal winners collected by the Dominion Museum were framed in groups like this one. In the centre is Brigadier-General Bernard Freyberg. Freyberg received a ‘Distinguished Service Order in Gallipoli Campaign for a brilliant personal exploit, involving hours of solitary swimming at sea. Awarded V.C. for conspicuous bravery at the Battle of Ancre’. AALZ 902 item 20, Archives New Zealand.

To track down portraits for the collection Thomson began by appealing directly to the next-of-kin of medal winners for photographs of their relative in uniform. Unstinting approval for the scheme was the norm. Mrs G. E. Simon, the sister of Edward Freed (who won a Military Cross at Messines) received one of the first requests from Thomson in mid-July 1917. Thomson informed Mrs Simon that portraits of New Zealand servicemen like her brother, ‘whose conduct has marked them out for distinction by their King and Country’, were being ‘secured in readiness’ for when they could be ‘fittingly displayed’ in a separate war museum.[iv] This overall objective impressed Mrs Simon, who promptly posted a photograph to Wellington.

Public interest was so high that the clerk in charge of processing the photographs was at times overwhelmed with work: in total the museum received around 1100 photographs between 1917 and 1921. A typical response came from the mother of the Military Cross winner Frank Greenish, who ‘fe[lt] very proud that [the photograph] should be included in the national collection’.[v] Similarly, the mother of another Military Cross winner, Clarence Seton, 'consider[ed] it a very nice idea to place the photos … of the brave men in the national war museum.’[vi]

Some next-of-kin judged Thomson’s memorial scheme worthier than others that had failed to galvanise their support. For example, the father of deceased Military Cross winner Charles Senior confessed that:

I have hitherto declined the invitations from the public press but [Charles’s] mother + I recognise that the purpose for which you require [the photo] is of an entirely different nature + we are sending you a ‘home portrait’ [,] one he himself liked best.[vii]

Captain Joseph K. Venables received his Military Cross ‘for courage and coolness on Active Service in France. Died of wounds in France.’ AALZ 25044 1/F719, Archives New Zealand.

It was unavoidable that some photographs depicted medal winners who had died, like Charles Senior, while on active service. However, this collection worked differently from imagery that the bereaved saw in other contexts, in that it presented an uplifting and heroic side to the war. And, collectively, the soldiers personalised and personified qualities, such as courage, gallantry and bravery, that were universally admired and aspired to.

Support for the scheme, however, was not unanimous. For example, one correspondent censured Thomson for his narrow focus on medal winners. Another – the winner of a DCM and Military Medal – politely declined the request, citing his humanitarianism and internationalism as reasons for both his participation in the war and lack of interest in Thomson’s collecting scheme.[viii]

This group of portraits features three ‘sons of Mr John Fraser, Maltby Avenue, Timaru’ who served in the NZEF (top row) and six members of the ‘Family of Mrs Willis, Karori’. The Willises served across the Empire, in Canadian forces as well as the NZEF and New Zealand Army Nursing Service. AALZ 902 item 5, Archives New Zealand.

Still, many donors provided original photographs without question for the museum to keep permanently. Others lent them temporarily for copying, sometimes because they had only one appropriate portrait of the medal winner. The administrative backlog meant that occasionally the return of a borrowed photograph was delayed. Australian-born DCM winner Joseph Ward, for example, had to remind the museum to return the print he had supplied for reproduction. The snapshot, taken by an old friend in Germany, was ‘treasure[d] more than … the decoration’.[ix]

Ward’s words reveal that wartime photographs were as precious as objects. In this vein, Thomson asked those with portraits if they also had war-related items, informing them that if they did, they would be much safer in a museum than in a domestic setting. However, this call met with a lukewarm response: photographs could at least be copied but objects with specific associations would be gone forever if donated to the museum. Besides, some artefacts or souvenirs were considered too personal for public consumption. As the mother of Military Cross winner Joseph Venables put it: ‘I have no souvenirs to send you; all he has sent, are too sacred to me and would not appeal to any but a Mother.’[x]

Captain Louis Noedl ‘enlisted as a Private in Sydney in the early part of 1915. Won the Military Cross in France 1916 and the Distinguished Service Order for conspicuous gallantry in making a reconnaissance for and directing the construction of urgently needed bridges across the Somme under exceptionally heavy fire. Captain Noedl is of Hungarian descent and his grandfather fought under the British flag and lost his life in The Crimean War.’ AALZ 25044 2/F110, Archives New Zealand.

Although each portrait carried particular sentimental meanings for friends and family, Thomson’s goal was to create from them a collection that was national in character. However, he applied the prevailing, capacious notion of ‘national’ identity – one in which New Zealand and Dominion identities co-existed under the umbrella of the British Empire. The collection therefore included NZEF medal winners, New Zealand-born or not, as well as New Zealanders who won their awards in other imperial forces including, for example, Victoria Cross winner Bernard Freyberg.

Yet for some New Zealanders, even a decoration for gallantry was insufficient proof of imperial loyalty. This doubt was cast over Louis Noedl, a Woodville man of Hungarian descent who won a DSO and a Military Cross in the Australian Imperial Force. Noedl’s father worried that museum visitors who saw his son’s photograph would judge him not by his actions but by his non-British surname. To deflect the prejudices that many New Zealanders directed at ‘enemy aliens’ during the war, he gave Thomson details of his family’s long-standing commitment to the Empire. Thomson accordingly added to the photograph’s caption that ‘Captain Noedl is of Hungarian descent and his grandfather fought under the British flag and lost his life in the Crimean War’.[xi]

Links to notable episodes in Britain’s past, such as the Crimean War, also mattered to Thomson, who hoped his war-related collecting would lead him to colonial history material for the Dominion Museum. To bring this material to light, he asked potential donors of photographs if there were family connections between the medal winner and an early Pakeha settler, or perhaps a soldier who had fought in the New Zealand Wars. Yet only a handful of men possessed this pedigree, including Military Cross winner William McKail Geddes, whose maternal grandfather was described as ‘one of the ancient landmarks of the Far North’.[xii] Geddes also claimed Ngāti Toro/Ngāpuhi whakapapa.[xiii]

Captain W. McKail Geddes received his Military Cross ‘for exceptional courage in reconnoitring enemy country under heavy shellfire. He was enabled to send back information of great value to his Brigade while his daring and resourcefulness contributed greatly to the success of our artillery.’ AALZ 25044 6/F747, Archives New Zealand.

The first framed groups of portraits were hung in the Dominion Museum at the beginning of 1918. Apart from a handful that celebrated ‘Families of Fighters in the Great War’, these were unsystematic groupings of assorted medal winners. This lack of order was of little consequence to visitors and the portraits’ meaning: En masse, they were the personal and public means though which the viewers appreciated, reconciled and were reminded of the complex concurrent meanings and emotions generated by the war.

Despite its popularity, Thomson’s scheme to collect privately-held photographs of medal winners of all ranks, and then to display them in public, was short-lived. In fact the precise date of the portrait gallery’s demise mattered so little that it appears to have gone unrecorded. That it was wound up without comment suggests that the portraits had run their course as a focus for war-related reflection.

On the other hand, increasingly through the 1920s, Anzac Day and community war memorials became primary media for public remembrance, the time and places utilised by for most New Zealanders to observe the ongoing impact of the Great War. Yet it is appropriate that during the war’s centennial, we review the photographs described above, and the motivations behind their collection for and donation to the museum, so that we can see them in relation to these dominant ways of remembering the First World War.

Footnotes

[i] For further details see Kirstie Ross, ‘“More the books can tell”: Museums, Artefacts and the History of the Great War’, in Katie Pickles et al, eds, History: Making a Difference, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, 2017, pp. 224-48.

[ii] Evening Post, 17 March 1917, p. 6.

[iii] The photographs are in two series: AALZ 902 and AALZ 2504, Archives New Zealand. Correspondence related to the photographs is in AALZ 907.

[iv] Thomson to Mrs G. E. Simon, 13 July 1917, AALZ 907 box 7, Archives New Zealand.

[v] Mrs Greenish to Thomson, 30 August 1917, AALZ 907 box 7, Archives New Zealand. Greenish’s portrait appears on AALZ 902 item 41.

[vi] Mrs E. G. Seton to Thomson, 5 January 1920, AALZ 907 box 14, Archives New Zealand. Seton’s portrait appears on AALZ 902 item 63.

[vii] Oliver Senior to Thomson, 5 May 1920, AALZ 907 box 14, Archives New Zealand. Senior’s portrait appears on AALZ 902 item 71.

[viii] Tom Parsons to Thomson, 15 August 1920, AALZ 907 box 13, Archives New Zealand.

[ix] Joseph Ward to Thomson, 6 October 1920, AALZ 907 box 14, Archives New Zealand.

[x] Mrs C. Venables to Thomson, 31 March 1918, AALZ 907 box 16, Archives New Zealand. Venables’ portrait appears on AALZ 902 item 25.

[xi] Robert Noedl to Thomson, 14 February 1919, AALZ 907 box 13, Archives New Zealand. Noedl’s portrait appears on AALZ 902 item 42.

[xii] Observer, 2 December 1904, p. 4.

[xiii] Mary Geddes to Thomson, 1 October 1917, AALZ 907 box 7, Archives New Zealand. Geddes’ Scottish grandfather William Webster arrived in New Zealand in 1839. In 1850, he married Annabella (Hanapara) Gillies whose mother was Ngāti Toro. Jennifer Ashton, At the Margin of Empire: John Webster and Hokianga 1841-1900, AUP, Auckland, 2015, p. 99. Geddes’ portrait appears on AALZ 902 item 27.