Did you know that the New Zealand troopship Tahiti became infamous as a 'death ship' when the deadly influenza virus ravaged many of its 1217 passengers in August 1918?

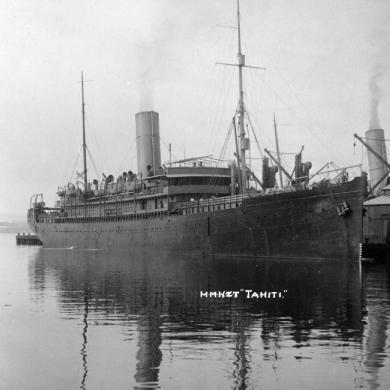

The SS Tahiti, the 5800-ton ocean liner famous as the ‘death ship’ of 1918, was built in Scotland in 1904. Purchased by the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand in 1911, with the start of the First World War she entered service as a troopship. Serving as HMNZT (His Majesty’s New Zealand Troopship) Tahiti, the vessel was part of the convoy transporting the first detachment of ANZAC troops in late 1914. In 1915 the Tahiti brought back to Wellington the first contingent of troops wounded in the Gallipoli campaign.

On 10 July 1918 the Tahiti left New Zealand carrying the 40th NZ Reinforcements, a group of mostly replacement troops under Lieut. Colonel R C Allen. Including the troops, support staff, and ship’s crew there were 1217 people aboard. New Zealand had, at this time, not been significantly affected by either the first or second waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic and thus those aboard had no exposure to and thus no resistance against the virus. The troops aboard the Tahiti, some of the last replacements sent to the Western Front from New Zealand, were also some of the first New Zealanders known to suffer from the infection.

Passing an uneventful voyage around southern Africa, on 22 August the Tahiti met her convoy group at Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. Upon arrival the officers aboard received reports of illness in Freetown, which had just become infected by the deadly second wave of the 1918 influenza, and those onboard were prevented from disembarking. This did not prevent local workers from resupplying the ship as it waited in harbour, however. Since influenza can be infectious for a day before symptoms appear, these workers could have felt fine and still spread the disease.

HMNZTS SS Tahiti in Wellington Harbour. Image courtesy of Te Papa, registration number: PS.002972

The influenza is thought to have been brought to Freetown by the HMS Mantua, an armed cruiser which had developed influenza onboard two days after leaving an infected London on 1 August. Unfortunately, this was the vessel which hosted a meeting of all the wireless operators and captains from the ships in the convoy. Having attended the meeting aboard a still infected Mantua, the captain and the wireless man likely brought the infection back to the Tahiti.

The Tahiti left Freetown on 26 August, heading in convoy to Plymouth, Great Britain. This is also the day when the first cases of influenza reported to the ship’s hospital. The worst day for the outbreak onboard was three days later, with more than 800 people, two-thirds of everyone aboard and including both doctors, were sick with influenza. This shows how infectious this disease was, and how quickly it could be transmitted in a crowded environment. Eventually roughly 90% of those on the Tahiti became ill from influenza, or 1100 of the 1217 people onboard.

A view of the bunks in one of the sleeping accommodations aboard the troopship Tahiti. Image courtesy of National Army Museum, accession number: 1990.618

After the war, a Court of Inquiry was held to review the circumstances around the illness on the Tahiti. It found several factors which may have contributed:

- Overcrowding had been an issue which troops aboard had complained about since leaving New Zealand. The vessel had originally been built to hold 650 passengers and crew, but in August 1918 it held nearly twice that number. While this was not unusual for troopships in the First World War, the combination of close quarters and poor ventilation were prefect for transmitting airborne diseases such as influenza. This was also reflected in more severe infection in those sleeping in rooms with bunks rather than hammocks, as ventilation was worse in bunkrooms.

- The Tahiti’s medical staff and facilities were quickly overwhelmed by the number of cases of influenza, and as elsewhere the trained medical professionals were generally infected quite early in the outbreak. As the numbers of ill rapidly outgrew the available hospital beds onboard, their isolation from those not yet infected became impossible.

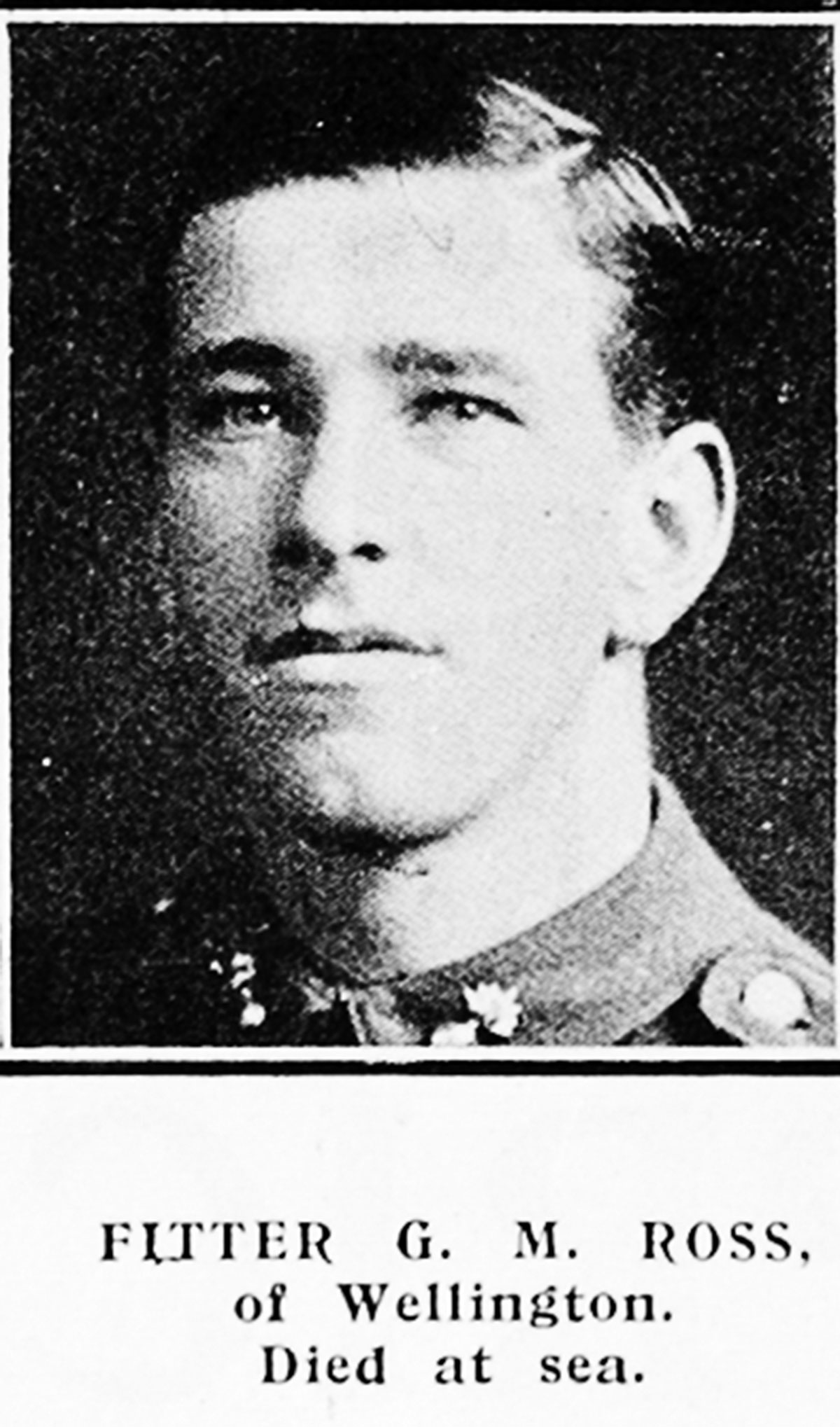

George Mervyn Ross was one of the Tahiti's influenza victims who was buried at sea. Image courtesy of Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, AWNS-19181031-41-7

The Ross family installed this plaque to George's memory in the Karori Cemetery. Image courtesy of Underground History.

The burials at sea began almost immediately. On 2 September alone there were six such burials, and by the next day 33 deaths had been recorded, including a delirious man who jumped overboard. The men (and one woman) who died were generally healthy and between 25-34 years of age. These were young people who had been healthy when the Tahiti reached Sierra Leone, and had succumbed to influenza in the fortnight’s voyage to Britain.

The Tahiti finally reached Plymouth on 10 September, 1918. By this date 68 had died, and another nine would pass ashore. The situation onboard was so severe that special trains were sent to Plymouth to transport the ill to influenza hospitals. Six weeks after arrival in Britain, only 260 of more than 1100 troops form Tahiti were fit for deployment. Seven percent of those who started the voyage from New Zealand died from the influenza, making the outbreak on the Tahiti several times more severe than that which eventually struck New Zealand itself.