The national war effort went beyond service in the armed forces. In these short personal stories, we look at some of the experiences of New Zealand's women at home during the war.

Civilian women inside a supply depot. Alexander Turnbull library, Ref: 1/1-008352-G (detail) https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22437589

No New Zealander was immune from the impact of the Great War. Approximately 100,000 men and women – representing almost ten per cent of the country – served overseas during the war, and tens of thousands more served at home. The national war effort went beyond service in the armed forces though. Whole towns and cities contributed to fundraising campaigns for various causes, employment roles were shaken up with a substantial portion of the workforce abroad, economic pressures added strains on vulnerable people, and fears for loved ones abroad – as well as fears of enemies at home – filtered throughout society.

Significantly affected by all these factors were New Zealand’s women. The short biographies below cover some of the extraordinary stories of women impacted by the war at home; those who replaced the men on farms, in banks and offices or did voluntary work making comforts and clothing for the troops or raised money for the women and children of Europe displaced by the war raging around them. And, of course, the army of women who kept businesses, farms and households afloat whilst their menfolk were away.

The biographies come courtesy of Fiona Baverstock, the curator behind Women of Empire 1914-1918. The exhibition, which toured New Zealand in 2016, told part of the women’s stories through the outfits they would have worn one hundred years ago.

Annie Gertrude Todhunter

We will find them

Determined to put families out of their misery and trace every missing son, husband and brother, Annie Gertrude Todhunter used her contacts in Switzerland and London. As a Red Cross volunteer in the Christchurch Branch, she single-handedly organised the Missing Soldiers’ Enquiry Bureau. Through her friend in Bern, she organised for the Swiss Red Cross to buy and distribute parcels to New Zealanders taken prisoner. Through her contacts with the British Red Cross and the New Zealand War Contingent Association in London, she organised for searchers to scour the hospitals and cemeteries of England and France for missing men. She marshalled people to interview all returning soldiers who might have information on the fate of their mates. She published lists, circulated photographs, wrote letters, contacted families and kept meticulous records. Initially, she and her volunteers funded the entire operation themselves, tirelessly raising funds and donations of goods. Eventually, the authorities saw the value in the work and lent support.

Mildred Amelia (Mīria) Tapapa Woodbine Pōmare. Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/2-043506-F.

Mrs Pōmare

The best of both worlds

Mildred Amelia Woodbine Johnson – Mīria Tapapa –— was comfortable with both names and both sides of her heritage. Her Poverty Bay landowner father gave his daughter every advantage a young lady of social standing could expect. Her mother, Mere Hape, educated her in Māori language and culture. In 1901 Mīria married physician, surgeon and Maori Health Officer, Māui Pōmare, who later entered Parliament. In 1915, Mrs Pōmare and Lady Liverpool, wife of the New Zealand Governor, set up Lady Liverpool’s and Mrs Pomare’s Maori Soldier’s Fund to provide comforts for Maori Contingent soldiers, organizing send-offs, homecomings and hospital visits. She was appointed an OBE in 1918, becoming Lady Pōmare in 1922 when her husband was knighted. Lady Pōmare continued to serve both the Māori and Pākehā communities throughout her life, a driving force in organizations such as the National Maori War Fund, the Pioneer Club, Red Cross, Girl Guides and YWCA.

Dr von Danneville

Hysteria on the home front

She cut her hair super short, wore a tailored skirt and jacket, shirt, tie and ‘mannish’ hat. She claimed to have been a ‘correspondent’ reporting on the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. In Wellington, with sketchy medical credentials, she had helped establish a clinic based on a German doctor’s methods. She sounded German. Dr Hjelman von Danneville was just the sort to arouse the enmity of the Women’s Anti-German League and the Solicitor-General, who stated: ‘…there is grave ground for suspicion that this person is a mischievous and dangerous imposter… There is much reason to suspect that she may be a man masquerading as a woman…’ Never mind that she was actually Danish, never mind the protestations of her colleagues and patients, on 26 May 1917 she was dragged off to Somes Island Internment Camp in Wellington Harbour. After six weeks there, she succumbed to a ‘severe nervous breakdown’ and was released into the custody of a Mr Spencer but the Anti-German League hadn’t finished with her yet - they reported to the Defence Minister that the citizens of Geraldine were ‘up in arms’ that this woman was in their midst and he promised to ‘have her removed’. She wisely left New Zealand for Australia in November 1919.

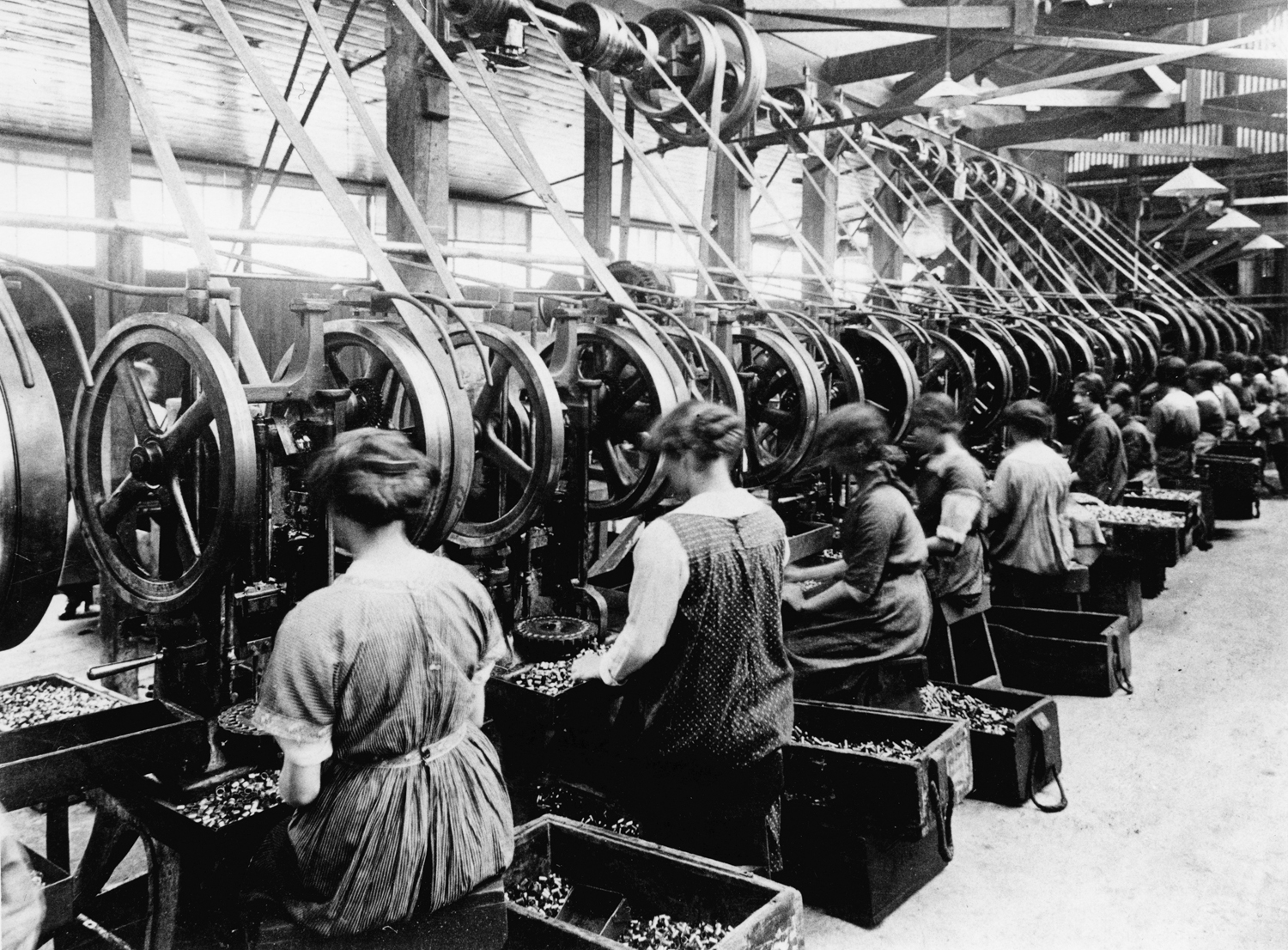

Civilian women inside a supply depot during the First World War. Such depots collected donated goods and sent them on to soldiers at the front. Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/1-008352-G.

Harriet Gardner

Knitting Heroine

Harriet Gardner was a widow in her seventies from Rangataua on the southern edge of Tongariro National Park. Harriet would often wake as early as four in the morning and, despite poor eyesight and the inadequate light of candle or oil lamp, would start knitting. Socks. 1.36 pairs for every single week of the war to be precise. She bought much of the wool from her meagre pension, washed every skein and made sure the completed socks were shipped off to the troops. The people of Rangataua were extremely proud of her efforts and wrote to Lady Liverpool, wife of the New Zealand Governor, seeking recognition for Harriet. Some 900 patriotic societies had blossomed in response to Lady Liverpool’s appeal to the women of New Zealand to do their bit. Her Excellency’s Knitting Book was a must have. The Governor and Lady Liverpool did indeed write a letter of appreciation and thanks to Harriet Gardner, which was unfortunately lost in a house fire some years ago.

With so many men serving in the armed forces, women entered workplaces traditionally occupied by men. Employment conditions were often far from ideal, and in most cases the women were expected to vacate their roles when the men returned home. This image of women workers at the Colonial Ammunition Company in Mt Eden, Auckland, comes courtesy of the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

Jessie Aitken

Feminist, socialist, pacifist, mother of eleven

Jessie Aitken’s politics were an inevitable product of her upbringing. Born Jessie Fraser into rural poverty in Scotland and raised in a struggling mining family in Westland New Zealand, she brought up a family of eleven – with precious little support from her husband, John Barr Aitken, who was found dead drunk – and dead – face down in a Nelson gutter in November 1907. Jessie moved to Wellington and took up feminism and politics – the Housewives’ Union, the Social Democratic Party, the Labour Party and the Women’s Anti-Conscription League. She became President of the Wellington branch of the Women’s International League, promoting international co-operation rather than war and campaigned vigorously against government ill-treatment of conscientious objectors. As the elected Labour member of the Wellington Hospital and Charitable Aid Board, she pursued women’s and children’s health and welfare issues, providing support for the widows, widowers and orphans of the influenza epidemic in 1918/19. Jessie continued to campaign, particularly for the right for women to stand for parliament – she herself stood unsuccessfully for election to Wellington City Council. She resigned from the Labour Party and the Hospital Board in 1920, joining family in Melbourne for a number of years. She died at her daughter’s home in Wellington in 1934.

Mary Newlove

It's a long way from Takaka

The postmaster at Takaka couldn’t face it. Twice already in the past week, he’d delivered telegrams and he couldn’t do it again. The local minister had taken the envelope in his stead and we can imagine Mary Newlove backing away from the door, as if not knowing the contents of the envelope would make them go away. Widowhood had been pain enough, this was incomprehensible. Three sons dead in a week. Attempting to take a ridge at Passchendaele, Charlie Newlove was one of the 320 New Zealanders killed on 4 October 1917. Keen to press home a perceived advantage, the high command threw everything at it on 12 October – the blackest day in New Zealand military history. By the end of the day 843 men were lying dead in the mud, amongst them Ted and Leslie Newlove. George Newlove, still in harm’s way, survived. The encompassing curve of the Tyne Cot Memorial, near Passchendaele, bearing the names of the three Newlove brothers, mirrors the magnificent, sweeping curve of Golden Bay – a world apart. How could this place whose name Mary could not pronounce be the last resting place of three of her boys?

Women of Empire Exhibition, 2015, showing costumes associated with Annie Gertrude Todhunter and Mrs Pōmare on the left. Photo courtesy of Nelson Provincial Museum.

Women of Empire Exhibition, 2015, showing costumes associated with Jesse Aitken and Dr von Danneville. Photo courtesy of Nelson Provincial Museum.

Women of Empire Exhibition, 2015, showing costumes associated with Harriet Gardner on the far left and Mary Newlove on the far right. Photo courtesy of Nelson Provincial Museum.