While training in Egypt, the New Zealand troops came to be dubbed ‘Massey’s Tourists’ because of all the sightseeing and revelry in which they indulged.

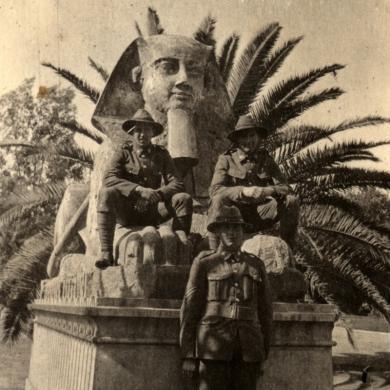

Three South Canterbury soldiers posing in front of an Egyptian sphinx. Courtesy of the New Zealand National Army Museum, accession number: 1993.1284

Between December 1914 and the Gallipoli landings on 25 April 1915, the first drafts of New Zealand’s First World War troops completed their military training in Egypt. When not taking part in monotonous marches through the desert, improving their marksmanship and bayonet skills, or practising co-ordinated operations, the men were able to explore the wonders of this ancient land.

Many men had their photo taken in front of the pyramids at Giza. Many more sampled the delights and vices offered to them in cosmopolitan Cairo. Egypt’s sights, sounds and smells were unfamiliar to the New Zealanders, as few of the men had travelled overseas or mixed with people from other cultures before the war. Because the New Zealand government had funded the troops’ voyage to North Africa – and indeed their sightseeing trips – the soldiers came to be dubbed ‘Massey’s Tourists’ after the then prime minister, William Massey.

It was along the Suez Canal that the New Zealanders got their ‘first real glimpse of Empire’. Calls went back and forth between the men on the New Zealand and Australian transport ships and the Indian troops guarding the banks of the canal. The almost 8,500 men of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) Main Body and 1st Reinforcements had spent seven weeks at sea to arrive at this point. For most of that time they – and their officers – assumed they were on their way to England for further training before eventually going into battle against the Germans on the Western Front.

The plan changed after 5 November 1914 when Britain declared war on the Ottoman Empire, which had allied itself to the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. While the NZEF was still at sea it was decided by British military authorities that they, along with the men of the Australian Imperial Force in that same convoy, would be re-directed to Egypt. Here they would continue their training, protect the Suez Canal, and help stabilise the rule of Sultan Hussein I, who had recently been installed as leader following Britain’s formal seizure of the territory from the Ottoman Empire.

Three friends in Zeitoun Camp, 1915. From top to bottom: 12/140 Private Ernest "Ernie" Jeffs, 9/803 Corporal Curll Alexander Gordon Catto, and 4/524 Lance Corporal David Kerr Haig. Image courtesy of the New Zealand National Army Museum, accession number: 1991.884.

On 3 December the NZEF men disembarked at Alexandria and boarded trains that took them to their camp at Zeitoun, 9 kilometres north-east of the Egyptian capital, Cairo. Trooper Alfred Cameron noted the scenes along the railroads as being ‘of much interest and novelty.’ At first the men slept out in the open before a sprawling settlement of bell tents sprang up. Collections of coloured pebbles ornamented the tents, depicting regimental crests and mottoes, native New Zealand birds or Māori proverbs.

It was in the desert surrounding Zeitoun that training commenced in earnest. As Fred Waite wrote in his semi-official history, The New Zealanders at Gallipoli, ‘early every morning the infantry battalions paraded in full marching order and trudged through miles of sandy desert. Like so much of the soldier’s life, his work was not interesting, but it was necessary’. Meanwhile the men of the Mounted Rifles exercised their weary horses, which had also been on board the transport ships. All troops took part in target shooting practice, inspection parades, formation drills and large-scale field exercises.

Infantrymen of the Wellington Battalion in full marching order on a route march in the desert, early 1915. The NZEF's training grounds were 5-6 kilometres from Zeitoun Camp, requiring a long walk to and fro each day they trained. Image courtesy of the New Zealand National Army Museum, accession number: 1992.756.

Not all the NZEF's training was boring. Here the lads are "Tossing a Trooper" - exercising for physical training. Image courtesy of the New Zealand National Army Museum, accession number: 1993.1284.

The New Zealanders also joined a march through the old and new quarters of Cairo, which was designed to impress upon its inhabitants the power of their new British rulers. Many soldiers commented on the difference between the quarters. Private Oswald Norris noted that the modern, European sections of Cairo possessed some ‘wonderful buildings … certainly the most substantial structures I’ve ever seen.’ He continued in his letter home, ‘Of course the city is simply full of men in uniform, Australians, English Territorials and ourselves. You can perhaps imagine the well-lit streets, the flashing of uniforms, the Egyptians in all manner of dress, most of them in their red fez caps.’ In contrast, the dilapidated ‘native quarters’ were written of disparagingly. Trooper Gordon Harper described them as ‘mile[s] of alleys and slums and variegated stinks’; others labelled them ‘squalid’, ‘dirty’, ‘stinking’ or ‘very immoral’.

An unidentified battalion band leads a New Zealand battalion through the streets of Cairo's modern quarter, possibly during a march to impress local residents and quell potential dissent in December 1914. Note the Allied flags which festoon the buildings above. Image courtesy of the New Zealand National Army Museum, accession number: 2006.88.

A sense of duty may have made the monotonous training bearable, but it was the parallel sense of adventure that enticed the New Zealanders to explore Egypt’s main tourist sites, all within easy reach of Zeitoun. Popular attractions included Cairo’s Zoological Gardens, the museums filled with ancient relics, theatrical or vaudeville performances, and of course the Sphinx and Great Pyramids of Giza. In these pursuits Massey’s Tourists could while away their spare time, and spend their pay on souvenirs and new experiences.

Fred Waite wrote of how, on Sunday afternoons, ‘groups of men wandered further afield – to the mighty Pyramids of Ghizeh, there to pose on the protesting camels for the conventional photograph of tourist, sphinx and pyramid.’ A week after arriving in Egypt, Oswald Norris wrote home to his dear Aldyth, ‘Along this road we went yesterday, 7 of us, to see the Pyramids, and we saw them! But if you went to Kincaid’s and bought a box of dates with Sphinx on the cover you would get a very good impression of what they are like.’

Tourism operators targeted the New Zealand and Australian troops, who were better paid than their British counterparts. Mr Daniel Balter, a ‘tourist contractor’, distributed a pamphlet to the New Zealanders advertising a four-hour tour with the following itinerary: ‘passing the most fashionable quarters of the city to Old Cairo, visiting the Island of Rhodah, where a rowing boat will convey the excursionists to the Garden of Pharaoh’s daughter, visiting also the Nilometer, and showing the spot where Moses (the Law Giver) was picked up in the bulrushes by the princess of Pharaoh.’

Alfred Cameron recorded how he spent one particular day on leave: ‘Went to Zoological gardens. Ride out very pretty…. Crossed the Nile bridge and dozens of house boats along the banks. Some beautiful dwellings en route – resemble large mansions, white stone. Gardens laid out lovely, splendid assortment of animals. Back to city at 5-30 pm. Went to a picture and variety show until 8. Had four course dinner at the Grand Continental Hotel.... Back to camp 9-30.’

A group of eight soldiers in front of the Sphinx and pyramids at Giza, Egypt on Boxing Day 1914. Unknown photographer, collection of Puke Ariki, New Plymouth, accession number: PHO2013-0138.

Three soldiers of the 2nd (South Canterbury) Company posing in front of a Sphinx. They are identified as 6/568 Sergeant Joseph Henry Wallace (in front, killed in action at Gallipoli on 7 August 1915). Left is 6/545 Private Robert Henry Smith and at right 6/502 Private John Clayton Mason. Image courtesy of the New Zealand National Army Museum, accession number: 1993.1284.

An example of the many souvenirs the men stationed in Egypt could send home to friends or family members. Image courtesy of Damien Fenton, sourced from New Zealand and the First World War.

The military authorities quickly became aware of the risks associated with allowing thousands of young men to roam the less savoury areas of Cairo in search of pleasures and thrills. A 10.30 p.m. curfew was introduced, and recreation facilities and beer canteens were opened at Zeitoun camp in an effort to keep the New Zealanders away from the temptations of Cairo. Similar facilities were not provided for all of the vices in which New Zealand troops indulged.

The scene at one of Zeitoun Camp's beer canteens after a big night in. Such behaviour was tolerated as it was preferable to having the men let loose in Cairo. Image courtesy of Matt Pomeroy.

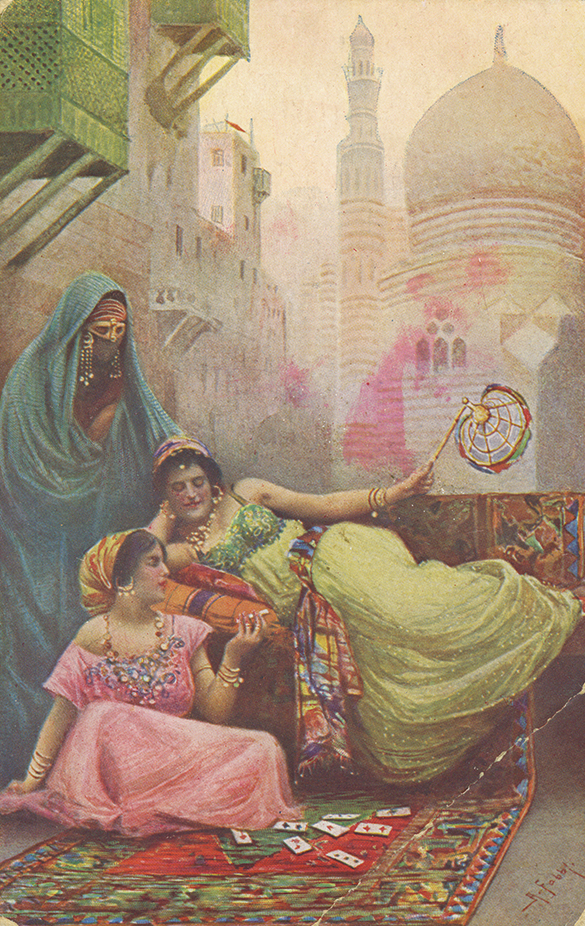

Cairo was home to over 3000 licensed prostitutes, and thousands more unlicensed ones. Many plied their trade in the Wasa’a district, known to the troops as the ‘Wazza’. Despite being warned against the spiritual and physical dangers of prostitution, New Zealand and other foreign troops ensured that the brothels did a roaring trade. By April 1915, 445 New Zealanders had been diagnosed with venereal disease. Most of these men were treated in a special hospital run by the Australians, which was surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards.

Away from home, in a new and cosmopolitan environment, many of the young men of the NZEF succumbed to what was considered evil temptation. Fred Waite later responded to the criticism Massey’s Tourists received back home for their perceived immorality. ‘It is easy to condemn the men who sometimes are not temperate in all things, but the soldier finds it easy to live a prodigal life. He reasons, perhaps quite wrongly, that he may as well eat, drink and be merry, for to-morrow he may be in the casualty list.’

'The Fortune Tellers' – Egytpian courtesans. This postcard was sent to New Zealand from Zeitoun Camp, 10 January 1915. Courtesy of Matt Pomeroy.

In a particularly notorious incident on 2 April 1915, a group of drunken New Zealand and Australian soldiers rioted in the Wasa’a district. Tensions had steadily been rising before the riot – fuelled by stories of price-gouging, theft and scams inflicted upon the Australasian troops. The riot flashpoint came when a group trashed a brothel where they suspected they had contracted a venereal disease. Hundreds of men joined in what became known as the ‘Battle of the Wazza’, burning property, destroying much of the district and assaulting many of its inhabitants.

The scene following the riot that came to be called the 'Battle of the Wazza', in which one of Cairo's brothel districts was trashed. 'Haret el Wasser, Cairo, Egypt.' Paterson, E B: 139 photographs relating to World War One experiences of Hugh Townshend Boscawen. Ref: PAColl-0914-1-53-1. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Only after several hours were the military police able to restore order. Sergeant Godfrey Hammond recalled the quelling of the riot in a letter home to his mother: ‘The Military police had to resort to firing on the crowds with the result that several soldiers were seriously wounded. I happened to be in town with Charlie Stewart & Percy Best at a picture when two bullets came crashing through the walls, one just missing me by a few inches.’

It was never discovered who was responsible for the Battle of the Wazza. The New Zealanders and Australians blamed each other, and neither party cooperated with the military court of enquiry into the incident. Shortly after the riot, however, senior officers had their mind on other matters. They received orders to prepare for embarkation to the Dardanelles, where Massey’s erstwhile tourists would fight and die in the Gallipoli Campaign.