Ten New Zealand nurses drowned when the Marquette was torpedoed on 23 October 1915. Why were they and other medical personnel transported through submarine-infested waters on an ordinary ship rather than a hospital ship?

Surviving nurses from the Marquette. Image courtesy of the National Army Museum of New Zealand: 1986.1753.

When the British transport ship Marquette was sunk in the Aegean Sea on 23 October 1915, 32 New Zealanders were killed, 10 of them nurses, but their deaths need never have happened. The Marquette was not a hospital ship, marked with a red cross, so it sailed without the protection of the Geneva Convention and was therefore fair game for German submarines.

Early in October 1915 the medical staff of No. 1 New Zealand Stationary Hospital in Egypt were told to pack up. By the 19th they were boarding the Marquette in Alexandria. There were 36 nurses plus eight officers, nine non-commissioned officers and 77 orderlies of the New Zealand Medical Corps.

The Marquette was on its way to Salonika (Thessaloniki), where the British and French had been supporting Serbian forces since September. Also on the large troopship were the 500 men and officers of the ammunition column of the British 29th Division, plus 500 mules, some horses and many wagons loaded with ammunition.

The large troopship initially had an escort to shepherd it through the hostile waters, and its passengers took part in lifeboat drills. Despite some talk of submarine attacks, the nurses were relaxed. Sister Edith Popplewell later wrote that ‘there were rumours of torpedoes, of course, and we had lifebelt drills for two days, but we really hardly took it seriously I’m afraid’.

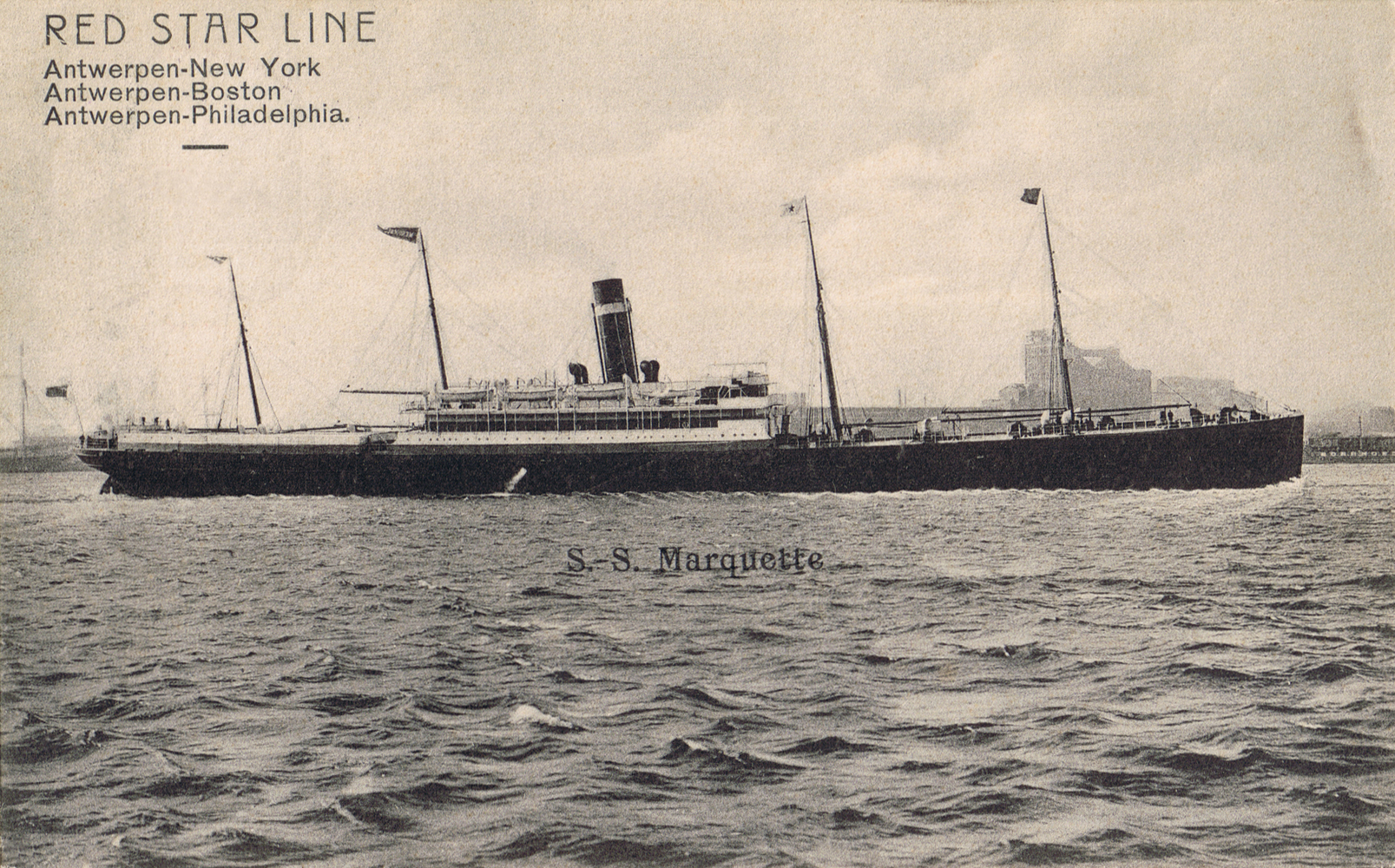

SS Marquette of the Red Star Shipping Line in its pre-war days working from Antwerp to the US Eastern seaboard posts of New York, Boston and Philadelphia. This postcard is dated 25 August 1910, and comes courtesy of Glenn Reddiex's private postcard collection.

On the morning of 23 October, Salonika was not far away, and the escort had been called off. Just after 9 am, in cold, grey weather, several nurses were enjoying a brisk walk on the deck when Jeannie Sinclair saw ‘a straight, thin, green line coming through the water’. The torpedo struck the ship well forward on the starboard side and almost immediately the bow dipped. Edith Wilkins remembered how, at that moment, the Marquette ‘quivered and then started to list’.

Without panic, the nurses grabbed their lifebelts, then silently and calmly took their places, 18 on each side of the ship, ready to get into the lifeboats. On the port side, one boat was lowered safely to the water. But the second, heavier, boat could not be freed from its davits. As the ship rose, the boat swung forward and fell heavily onto the one already in the water. Some nurses were killed immediately; others were fatally injured.

On the starboard side, nurses managed to scramble into the forward boat but as it was being lowered it struck an iron door and tipped upright, propelling five women into the sea. The boat, now damaged, pulled away from the Marquette but quickly capsized. When it was righted again, just six nurses were still aboard. Only four would survive.

As its former passengers and crew struggled or lay dead and dying in the cold sea, the Marquette sank, bow first. It took only minutes for the vessel to disappear.

German U-boat U-35, commanded by Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière, was responsible for the sinking of the transport ship Marquette. This 1917 photograph is courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, © IWM (Q 53032).

Mary Grigor, whose right arm had been crushed between a lifeboat and the ship, spent a long time in the water, clinging to wreckage, before a crew member saw her and the pair made their way to a half-submerged boat. Jeannie Sinclair owed her life to a Londoner she knew only as Joseph: ‘We floated with boards, lifebuoys and anything we could catch hold of, for seven, long hours.’

There were stories of immense courage. Nona Hildyard, injured by the bungled lowering of the starboard boat, sang bravely before she suffered heart failure and died in the water. Mary Gorman, both legs crushed, knew survival was impossible. She removed her lifejacket for others to use.

Rescue was a long time coming. The Marquette had been able to send only a very faint SOS signal, giving her position. But 30 minutes after this was received in Salonika, a second message came in, giving a different location, and the rescuing French and British destroyers rushed there. This communication had in fact been sent by U-35, the submarine that sank the Marquette.

So the wreckage and survivors were located only in the fading light of late afternoon. Cared for with great kindness on the vessels that saved them, the surviving nurses were transferred to the British hospital ship Grantully Castle and given clothes and comfort. Sister Wilkins appreciated the support given by the Grantully Castle’s English matron and Australian sisters, who ‘simply robbed their wardrobes on our account and did everything to brighten us up’.

The surviving nurses arrived at Salonika 'clad in borrowed clothes, Red Cross singlets and woollen khaki golf coats’. Image courtesy of the National Army Museum of New Zealand: 1986.1753.

After a roll call the next afternoon it was clear that 10 nurses had been killed: Marion Brown, Isabel Clark, Catherine Fox, Mary Gorman, Nona Hildyard, Helena Isdell, Mabel Jamieson, Mary Rae, Lorna Rattray and Margaret Rogers. The only bodies recovered were those of Rogers and Isdell. Also dead were 22 New Zealand men. Of the 741 onboard the Marquette, 167 had perished.

There were many deservedly admiring tributes to the nurses in the press, but some myth-making went on too. The captain of a French destroyer told a London newspaper that ‘when the French boats arrived, the nurses with one accord, called out: “Take the fighting men on first!”’ But this account, which was widely reported, did not ring true for the nurses who were there. By helping two sick orderlies as the Marquette was sinking, Mabel Wright and Ina Coster missed their chance of a place in lifeboat. In contrast to the exaggerated French account, Wright noted that ‘when the relief boats came to our rescue, nurses did ask that some of the men in an exhausted state should be looked after first’.

There was some controversy about the nurses who were left on deck before the Marquette sank, but this scandal faded in the face of the indisputable and openly admitted fact that the tragedy had been entirely avoidable: medical personnel and equipment should never have been on a transport carrying ammunition.

Why were the New Zealanders not put on the hospital ship Grantully Castle, which was sailing from Alexandria to Salonika at the same time, and had room on board? This question was never asked at the post-sinking inquiry on 26 October, and has never been answered.

.jpg)

A tram decorated with propaganda, photographed in late 1915 near Cathedral Square, Christchurch. Reference is made to the sinking of the Marquette under the title 'The German challenge'. Men were urged to avenge the drowning of the ten New Zealand nurses by enlisting for service. Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/1-007697-G, https://natlib.govt.nz/records/29941985.

Although polite, as always, when dealing with the seat of imperial power, the New Zealand Government was nonetheless certain about the cause of the tragedy. On 8 November 1915 the Governor, Lord Liverpool, wrote to the War Office: ‘In view of the loss of the “Marquette” my Government would be glad if arrangements could be made whereby medical units, such as stationary hospitals etc. should when possible be transferred by sea in a hospital ship.’

Hester Maclean, matron-in-chief of the New Zealand Army Nursing Service, later wrote in her autobiography that ‘it appeared a strange thing that the valuable hospital equipment, as well as the more valuable lives, should have been risked on an ordinary transport, which was conveying soldiers and munitions of war...’ Of the nurses’ courage during and after the disaster though, she wrote that ‘no words can express our admiration.’

In 1927 a chapel at Christchurch Hospital was opened in memory of the nurses lost in the Marquette sinking. In addition, the Nurses’ Memorial Fund was established in their memory and later that of the other five New Zealand nurses who died during the war. The fund would, Hester Maclean explained, ‘benefit any nurse… who may through sickness or misfortune need help,’ especially in her declining years.