On 10 December 1918, in what became known as ‘The Surafend Incident’, New Zealand, Australian and British soldiers raided a Palestinian village named Sarafand al-Amar and killed about forty Arab civilians in retaliation for the murder of a New Zealand soldier. In this article, historian Terry Kinloch explains what happened.

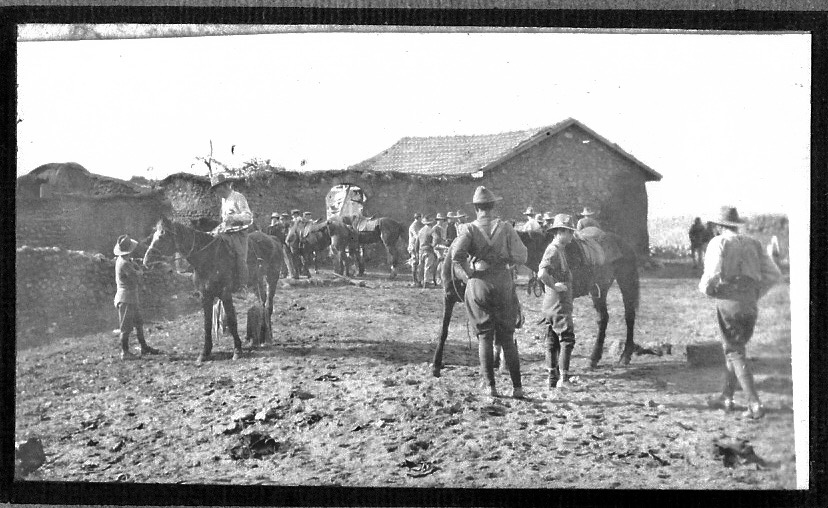

New Zealand and Allied troopers at the village of Surafend. Image courtesy of the Alan Hall Collection

On 30 October 1918, the First World War in the Middle East ended when the defeated Ottoman Turks signed an armistice. The soldiers of the victorious Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) put the war behind them and looked forward to a speedy return home. Before that could happen, however, a very serious incident took place that would tarnish some of their reputations for years afterwards. On 10 December 1918, in what became known as ‘The Surafend Incident’, New Zealand, Australian and British soldiers raided a Palestinian village named Sarafand al-Amar and killed about forty Arab civilians in retaliation for the murder of a New Zealand soldier.

In early December 1918, the Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division, which comprised Australian light horse and New Zealand mounted rifles regiments and British horse artillery batteries (as well as various support units) was encamped near Sarafand al-Amar (not far from Tel Aviv in modern Israel). On the night of 9/10 December 1918, 21-year-old Leslie Lowry, a trooper in the 1st New Zealand Machine Gun Squadron, was asleep in his tent on the outskirts of the divisional camp when his kitbag was stolen. Lowry is believed to have pursued and caught the thief in nearby sand dunes; in the ensuing struggle, Lowry was shot in the chest. After staggering a few paces, he collapsed and died. Lowry did not speak before he died, his killer escaped without being identified, and there were no independent witnesses to what took place.

Lowry’s property and an Arab skull cap were reportedly found at or near the site of the struggle, and barefoot tracks in the sand appeared to lead from there towards Sarafand al-Amar. This flimsy evidence was sufficient for some of Lowry’s colleagues to conclude that an Arab had killed him before taking refuge in the village. They threw a cordon around the village and an adjacent Bedouin camp to prevent anyone escaping, and waited for the EEF authorities to order a search to find Lowry’s killer. However, a military Court of Inquiry, which had more stringent rules of evidence, could only conclude that ‘an unknown person who had been stealing Government Property’ had killed Lowry. As the hours passed, the men in the cordon waited impatiently for the EEF headquarters to do something. The headquarters did take action – they ordered the soldiers to remove the cordon. The divisional commander, Major General Sir Edward Chaytor, protested vehemently, but was overruled. As soon as the cordon was lifted, fifteen to twenty Arab men – possibly including Lowry’s killer – immediately left Sarafand al-Amar.

-small.jpg)

A photo of the village of Surafend, Palestine, circa 1918-1919, taken by Wynton Herbert French. Courtesy of Wairarapa Archives, 06-78/3-19.

Some eighteen hours after Lowry’s death, frustrated soldiers decided to take matters into their own hands. In the early evening hours of 10 December, as many as two hundred of them armed themselves with bayonets and clubs before surrounding Sarafand al-Amar and the adjacent Bedouin camp. After allowing the women and children to leave and giving the village leader one last chance to surrender Lowry’s killer, the men moved into the village, supposedly to search for the murderer and give the remaining men a beating. If a beating was all that was intended, it went badly wrong, for at least forty Arab men were killed. Many others were badly injured, and most of the village buildings were burnt to the ground.

When the authorities commenced an investigation into the raid, they were confronted by an impenetrable wall of silence; the men of the division closed ranks and denied all knowledge of the raid, and the surviving villagers could not, or would not, identify any of the raiders. As a result, no one was ever tried or punished, either for Lowry’s murder or for the crimes committed at Sarafand al-Amar. The village was later rebuilt by the British Army, with New Zealand and Australia contributing £858 and £515 respectively towards the cost. In effect, this was an admission that soldiers of all three nations took part in the raid. Given Lowry’s nationality, it is possible, maybe even probable, that New Zealanders planned and led the raid, but that is not known for certain.

Why was there such a savage reaction to Lowry’s death? After all, a war had just ended in which millions of men had lost their lives. On the eve of going home, why risk imprisonment or worse by killing forty civilians in retaliation for the death of a single soldier? Most likely, Lowry’s death unleashed long-standing grievances against the Arabs – in effect, it was ‘the straw that broke the camel’s back’. Ever since the beginning of the Arab Revolt in 1916, EEF soldiers had been required to treat all Arabs with sensitivity so as to maintain their allegiance in the war. Arab claims of damage to crops or property by soldiers were usually upheld by the British authorities, and the men often had to pay for the damage out of their own pockets. Despite this, many soldiers believed – with some justification – that Arabs were responsible for murdering lone soldiers, looting their graves, stealing supplies and spying for the enemy. The inhabitants of Sarafand al-Amar were reportedly already under suspicion for digging up New Zealand graves in a nearby cemetery. While the war was going on, the soldiers had little opportunity to retaliate against such provocations; after the armistice, some men may have decided that wartime discipline and military law no longer applied. This perception, false though it was, cleared the way for retaliation in the event of further incidents. With time on their hands and dark thoughts in their heads, all that these men needed was another provocation; Leslie Lowry’s murder provided the necessary trigger.

New Zealand and Allied troopers at the village of Surafend. Image courtesy of the Alan Hall Collection

The soldiers who raided Sarafand al-Amar committed numerous criminal offences under British military law, including murder, aggravated assault, arson, breaking and entering, and malicious injury to property. These crimes were committed on active service, which made them more serious; the worst of them were punishable by death or long periods of imprisonment with hard labour. Indeed, the severity of the possible penalties may have convinced some witnesses to keep silent, to prevent their colleagues from being harshly punished for crimes against people they despised.

The actions of the raiders cannot be explained away as an over-reaction by stressed combatants caught up in the heat of battle. The raid was carefully planned and ruthlessly carried out by trained soldiers who knew that the war was over, and that the prospective victims were civilians who represented little or no threat to them. In this writer’s opinion, the raiders’ purpose from the outset was to kill at least some of the men they found in the village. If the deaths had resulted from the villagers fighting back, as was suggested, there would have been injuries amongst the attackers – but none were reported. They could not have seriously hoped to apprehend Lowry’s killer – they did not know what he looked like, and it is highly unlikely that he would still have been in the village.

The Sarafand al-Amar killings cast a dark shadow over the demobilisation of the Australian and New Zealand Mounted Division, and they still tarnish its reputation a century later. I believe this is unfair; of the tens of thousands of British, Australian and New Zealand soldiers who served honourably in the division between 1916 and 1918, only a tiny number participated in the Sarafand al-Amar raid. The raiders’ reprehensible actions on 10 December 1918 should not be forgotten or ignored (nor should Leslie Lowry’s post-war murder at the hands of a thief), but to allow the criminal actions of a relative handful of men to overshadow the wartime achievements of the division would be unjustifiable.

Terry Kinloch is a historian whose works include Devils on Horses: In the Words of the Anzacs in the Middle East 1916-1919. He also held a commission in the New Zealand Army from 1983-2013.