Did you know that when First World War conscription was extended to Māori, it was targeted at only one iwi? Learn how Waikato leader Te Puea Hērangi responded to the arrest of her people who resisted conscription.

Pānuitia tēnei pūrongo i te reo Māori

On 1 August 1916 the Military Service Act became law, initially imposing conscription on Pākehā only. The option was there, however, to compel Māori to perform military service. Eventually, in June 1917, conscription was extended to Māori, but the target of this extension was really one iwi – Waikato.

Following bureaucratic delays, the first ballot was drawn on 3 May 1918. Although the North Island had been divided into six Māori recruitment districts, the ballot was only applied to the Waikato-Maniapoto District. Just 59 of the 200 men called up in this ballot reported for examination to the medical board, and more than half of them were found to be unfit. It was up to the police to find the 141 defaulters and determine whether they had a valid reason for their non-appearance. If they did not, they would be arrested and taken to the Narrow Neck military camp in Auckland.

One of the balloted men who failed to appear before the medical board was the Māori King’s youngest brother, Te Rauangaanga Mahuta. Despite the young chief being only sixteen years old and therefore not eligible for the ballot, a telegram was sent to him asking why he had not appeared. When no reply was received, police in Hamilton were instructed to proceed immediately to arrest him. With no legal requirement for Māori births to be registered, he would have trouble proving his age to the satisfaction of the authorities.

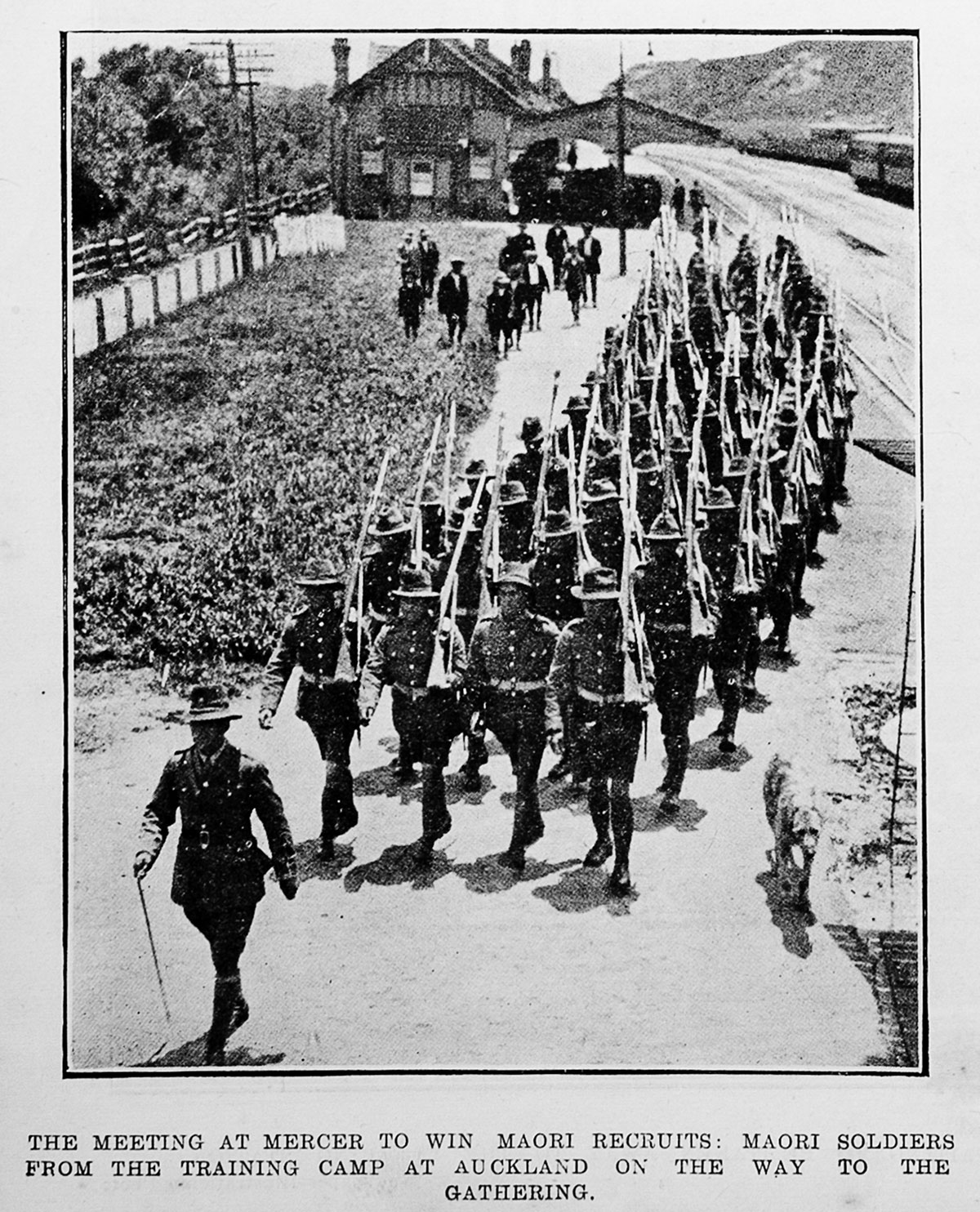

Several unsuccessful attempts had already been made to recruit Māori soldiers from the Waikato-Maniapoto District. Image courtesy of Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, Ref: AWNS-19161130-38-4.

Almost a week passed before police reconnaissance determined that Te Rauangaanga and other defaulters were almost certainly attending a ‘big meeting’ at Te Paina, Mercer. On Tuesday 11 June, a deliberately small party of eight policemen chosen for their tactfulness and led by Sergeant Cowan of Pukekohe met at Mercer. Sergeant Waterman, the township’s former policeman who was at that time stationed at Ponsonby, was one of the party, probably because of his wide knowledge of Māori customs. At 2 p.m. they boarded two police motor wagons to proceed to Te Paina, where they found about 400 people gathered at the pā. The hui was evidently expecting them, as a number of young women played brass band instruments as they passed through the gate.

The police were escorted into the crowded hall, where ‘Princess’ Te Puea Hērangi invited Sergeant Waterman to state the purpose of their visit. ‘We have come to apprehend the men whose names have appeared in the papers as having been balloted,’ he told an attentive audience. ‘We look to you, Te Puea, to help us to identify the men whose names I will read from this list. Although I would like it better if the men themselves would come forward as I read out their names.’

Rising to her feet, Te Puea greeted those present and their guests in the traditional manner. Then she responded to Waterman. ‘These people are mine … I will not agree to my children going to shed blood. Though your words be strong, you will not move me to help you. The young men who have been balloted will not go … You can fight your own fight until the end.’

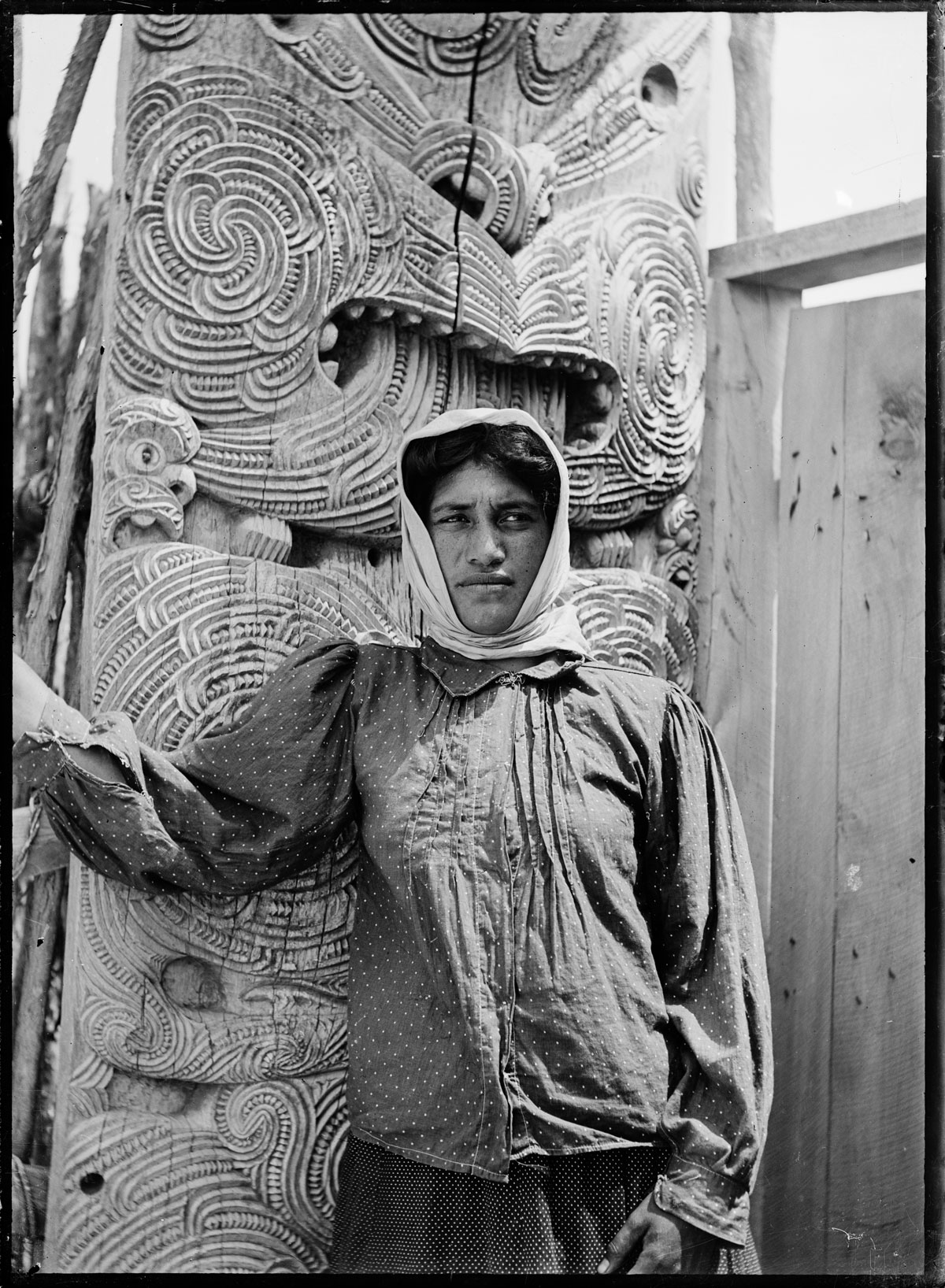

Portrait of Te Puea Herangi from the early 1900s. Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/2-001920-G.

Sergeant Cowan then read the list of names and asked any who were present to step forward. As expected there was no response, and after waiting for a minute or two, Sergeant Waterman and two constables moved first to arrest Te Raungaanga. The young rangatira was seated in the place of honour at the head of the room, surrounded by a number of young women, three of whom spread a flag in front of their chief as if to protect him. When Te Raungaanga did not come forward, the constables stepped over the flag and picked him up. A ‘great sigh went through the meeting’ as they carried him out of the whare. Te Puea’s parting words to her young cousin cut the tense atmosphere. ‘Be patient. Let the spirit of your father and also the spirit of your ancestors be with you. God bless you.’

An attendee at the hui later said that ‘if Te Puea had but raised her little finger there would have been bloodshed.’ Instead, she walked up and down in front of the rows of sitting people, murmuring that they must remain calm and quiet. The policemen then waded into the audience, arresting those whose names had been called.

In the end, only six other men were taken out. All had to be carried. When the operation was finished, Te Puea addressed the policemen again. ‘Return to your Government and tell them what I have said. I am not afraid of the law or anything else excepting the God of my ancestors … I will not allow any violence or blood to flow through my fingers … Go in peace and goodbye.’

In reply, Sergeant Waterman thanked Te Puea and the people for their behaviour. He also assured them he would return. Despite the stressful experience, those present at the hui considered that by making the authorities fetch the young men from the pā they had made a protest sufficient to satisfy the requirements of Māori honour and etiquette.

Te Puea Hērangi and a party of Tainui Māori attended a fundraising hui at Porourangi marae on the East Coast in 1918. Here she is pictured with Captain William Tutepuaki Pitt and Pitt's daughter, Peggy Alexandria. Image courtesy of the Ngata collection.

The seven men were driven to the railway station and with their police escort boarded a train for Auckland, where military police took charge of them. According to Colonel G.W.S. Patterson, the Officer Commanding of the Auckland Military District, by then the defaulters ‘had evidently relented to some extent as no difficulty was met with … the men walking quietly and getting aboard the ferry boat for conveyance to Narrow Neck Camp.’ It was hoped that by intermingling the conscripts with other recruits already in training, they would after a day or two ‘see the folly of their ways and … submit themselves for medical examination and attestation.’

By 1919 only 74 Māori conscripts had gone to camp out of a total of 552 men called up, and none were sent overseas. When the war ended in November 1918, the Māori in training were sent home, and all outstanding warrants were cancelled. Deciding what to do with the defaulters in custody was trickier. Despite the military's objections, Cabinet decided in May 1919 to release all Māori prisoners.

The imposition of conscription on the Waikato people had long-lasting effects, and the breach it caused has not healed even with the Waikato-Tainui Deed of Settlement signed in 1995. It was Waikato’s determined and public resistance to overseas service that made the government seriously consider, for the first time, the long-standing grievances around land loss, denial of access to resources and associated poverty which discouraged enlistment.

This article was adapted from Monty Soutar’s forthcoming book Whītiki: Māori in the First World War, due in 2019.