Did you know there were five by-elections in 1918? The results shook the political establishment, and suggested that there was significant disquiet amongst the public about the government's wartime policies.

The NZ House of Representatives around the time of the First World War. Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library.

By-elections can produce strange results. Sometimes the results are aberrations, where voters abandon normal loyalties to ‘send a message’. Sometimes, though, by-elections suggest that a political realignment is under way. This was the case with the five by-elections held during 1918, a century ago. With a sixth having taken place in December 1917, the contests cumulatively indicated that the new Labour Party, only formed in 1916, had already built a substantial following among voters, and that the Reform-Liberal coalition which had governed since 1915 was unpopular in many working-class communities. The results also suggested that there was significant disquiet about the governing coalition’s wartime policies.

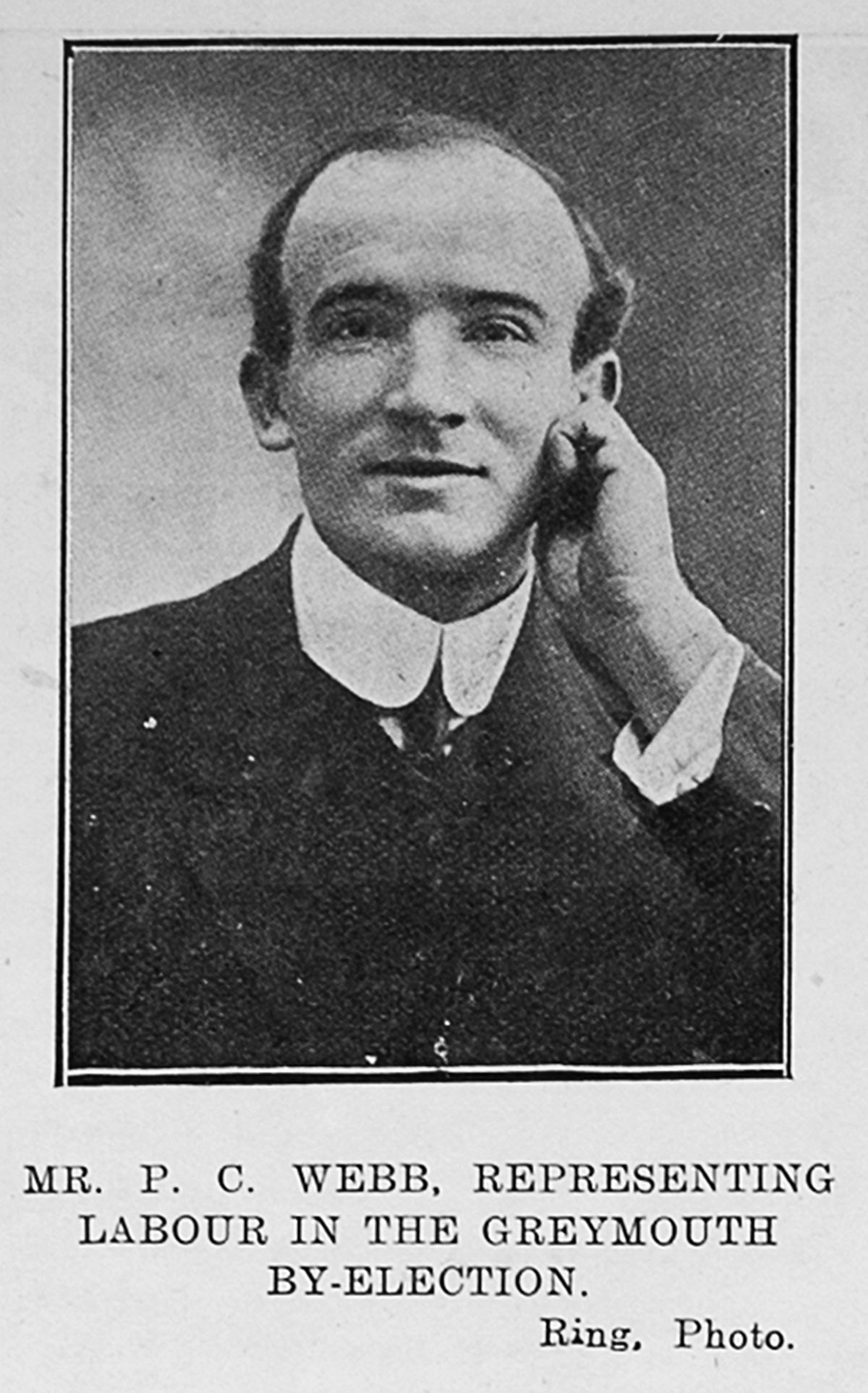

By-elections take place on the death, resignation, or disqualification of the sitting member. Paddy Webb, a former miner, had been Social Democratic, then Labour, MP for Grey since 1913. Opposition to conscription was widespread within the labour movement, and in May 1917 Webb was imprisoned for three months after he made an anti-conscription speech. Once released, Webb was himself conscripted. Webb, and many of his constituents, believed that it was more important that he continue to represent them as the only former miner in parliament. To demonstrate this, Webb resigned his seat and forced a by-election on 24 December. The government either refused to contest the seat or could not find a candidate, so Webb won unopposed. The Labour Party then appealed for Webb to be exempted from conscription as his occupation was of national importance. The Military Service Board rejected the appeal, thereby declaring that the legislature was of no significance. In March 1918 Webb refused to serve and was jailed for two years. As a consequence he forfeited his parliamentary seat, and would not return to the House until 1933 (when, ironically, he replaced Harry Holland).

A portrait of Paddy Webb, a former miner and later Labour MP, published in the Auckland Weekly News around the time of his 1913 election to parliament. Image courtesy of Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries. Ref: AWNS-19130724-54-2.

Labour’s candidate for the second Grey by-election, on 29 May, was Harry Holland, the radical socialist and editor of the labour newspaper, the Maoriland Worker. Holland had neither Webb’s easy charm nor a mining background, and he was vilified as ‘the Empire’s enemy’, but even as an outsider he won in a straight fight with the Reform candidate Thomas Coates, a farmer and lawyer who had been mayor of Greymouth.

Holland would go on to be the Labour Party’s parliamentary leader from 1919 until his death in 1933. Grey was not Holland’s first by-election. On 12 February he had fought Wellington North, which became vacant when the government appointed the hard-line Attorney-General, Alexander Herdman, to the Supreme Court (the last time such an appointment was made in New Zealand). Wellington North combined prosperous and poorer suburbs; Holland had won only 20% of the vote in 1914 but now standing against Wellington’s Reform mayor, John Luke, he took 36% and Reform’s share dropped from 55% to 42%. What was more important was that Holland in 1918 explicitly campaigned against conscription and the government’s wartime economics.

Group portrait of Unity Conference delegates (featuring Paddy Webb and Robert Semple) posed in front of The Maoriland Worker office, Wellington, taken 1913. Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/1-002596-F.

In September, Wellington Central’s Liberal MP Robert Fletcher died. Fletcher had taken nearly 65% of the vote in 1914 with labour support. But in 1918 Labour selected a rising star, Peter Fraser, to contest the by-election. Fraser had already demonstrated his talents as a political organiser managing Holland’s campaign in Wellington North; in Wellington Central he secured a commanding 57% of the vote, against a pro-conscription ‘labour’ candidate, a Liberal, and a clutch of independents. Fraser would hold the seat until his death in 1950, and, of course, be Prime Minister from 1940 to 1949.

Also in September the Reform MP for New Plymouth, died. The by-election on 10 October saw the Reform candidate, John Connett, challenged by an ‘independent labour’ candidate, Sydney Smith. Smith was a railwayman, active in the railway union, and the son of the late Liberal MP E. M. Smith. Smith also supported the war effort, including conscription, but turned a substantial Reform majority around to win by just over 51% (Smith would later join the National Party; the Taranaki by-election was the least comforting 1918 contest for Labour).

Cartoon of a street orator campaigning for political reform, from the Observor, 11 May 1918. Image courtesy of Papers Past.

Then the influenza epidemic claimed David Buick, the Reform MP for Palmerston North, and in that by-election on 19 December the Reform candidate, James Nash – the town’s mayor – won with an unimpressive 42%. Labour’s candidate was Alex Galbraith who took 36%; Labour’s James Thorn had won only 24% in 1914 but what was more significant was the Liberal collapse to a quarter of the vote and that Galbraith had openly campaigned as a radical. Indeed, he would later be a long-serving and prominent member of the Communist Party.

On the same day as Galbraith contested Palmerston North, there was a by-election in Wellington South. Since 1911 Alfred Hindmarsh, a lawyer, had been the seat’s Labour MP, and he served as the party’s first Parliamentary leader from 1916. Hindmarsh, who also died in the influenza epidemic, was regarded as a comparative moderate, although he firmly opposed conscription. Labour’s candidate in that by-election was Robert Semple, who at that time had a reputation as a firebrand (later, he would become rather more conservative). Like Fraser, Semple had been imprisoned during 1917 and campaigned against the government’s handling of the war; his 60% of the vote was a slight improvement on Hindmarsh’s 1914 result. In the 1919 general election, however, the Reform Party threw everything it had into unseating Semple, and succeeded. Semple returned to Parliament in 1928.

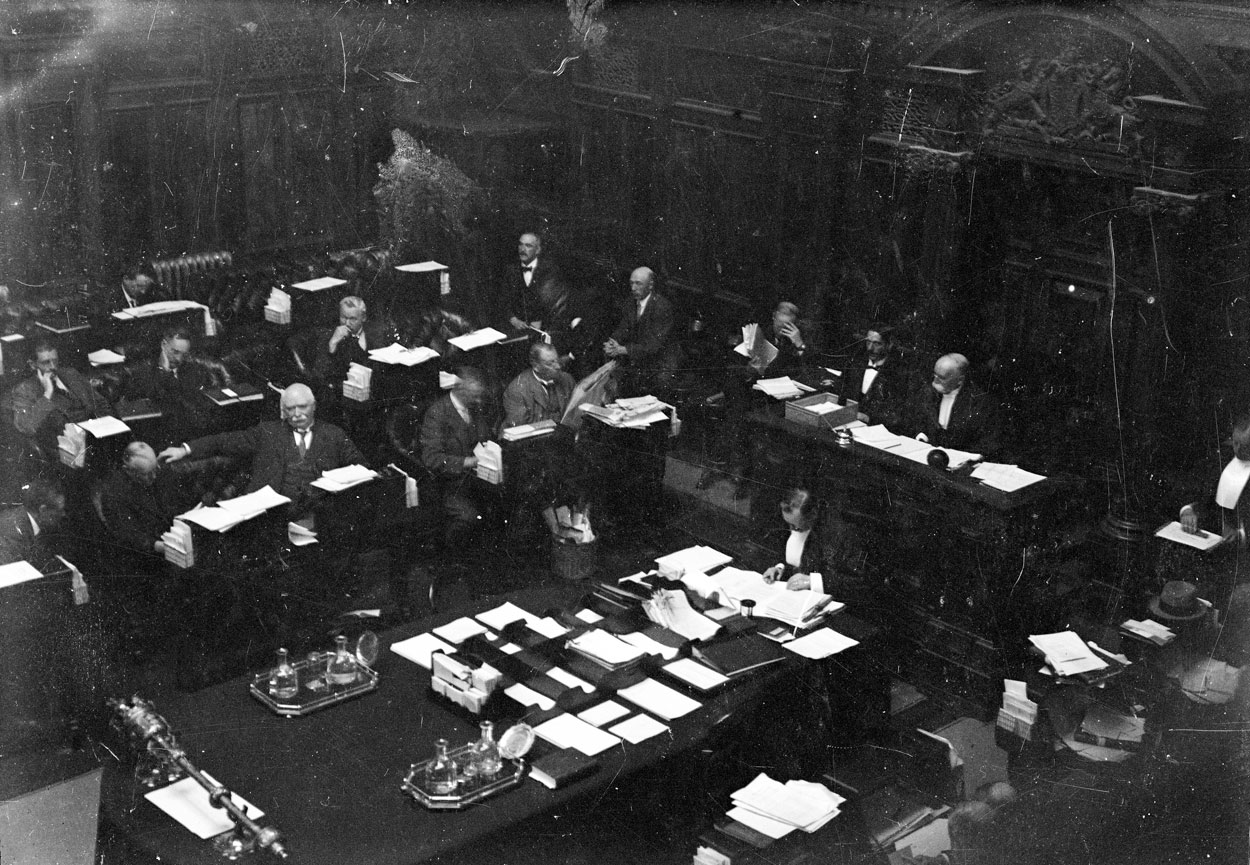

A photograph of the New Zealand House of Representatives from around the time of the First World War. Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/4-016962-G.

Each of the by-elections, of course, differed in important respects. The electorates varied widely in their social composition. Taken together, however, the results suggested that there was significant disquiet about the Reform-Liberal coalition’s wartime policies, especially on conscription, and in the perception, which Labour encouraged, that the economic burdens of the war were not being fairly shared. In most of the by-elections – New Plymouth was the exception, where the party did not field a candidate – Labour’s campaign was more or less radical, even as candidates emphasised bread and butter issues. The results suggested some desire for change, and they also demonstrated that the political imprisonment which some Labour leaders had suffered was not necessarily a liability. The party’s morale was greatly boosted by these by-elections, which suggested that Labour would remain part of New Zealand’s political landscape.