This year, as 100 years ago, New Zealand was at peace on 25 April 2014. We’d love to know what that means to you, and how you went about your day – the centenary of the last day 25 April was just 25 April.

Anzac Day this year marked the centenary of the last time that 25 April was just a day like any other day – before it became a signature date in New Zealand history.

Here in the WW100 Programme Office we are acutely aware of the meaning of Anzac Day as a day of remembrance, not just for those who served and fell at Gallipoli, but for those who have served in all conflicts to defend our country. This day next year will be one of the early milestones for the four-year First World War centenary programme, as we open the National War Memorial Park and mark the centenary of the Gallipoli campaign.

However, this year on the 25th of April we celebrated peacetime – a time when families and communities were free from the intense anxiety of not knowing whether sons or brothers or uncles or fathers were among the – at first only rumoured – casualties at Gallipoli.

The different experiences of New Zealanders on this day in history can be understood through accounts such as diaries, letters and newspaper reports; and will be recorded for the future on websites such as Facebook and Twitter.

25 April 1915: The origins of Anzac Day

Next year, on 25 April, it will be 100 years since New Zealand and Australian soldiers – the ANZACs – landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula, in present-day Turkey, during the First World War. The aim was to capture the Dardanelles strait, which would make it possible to attack Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. But at the end of the campaign Gallipoli was still held by the enemy and thousands of soldiers from both sides had lost their lives – more than 100 New Zealanders died on 25 April 1915 alone.

George Bollinger, a New Zealand soldier in the Gallipoli campaign. Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: PAColl-0049-1

In May 1915, as the official news of the casualties from the Gallipoli campaign reached the New Zealand public via newspapers, the Christchurch Press published an article titled ‘New Zealand’s Noble Dead’. It made note of the significance of the Gallipoli campaign as a turning point – from a time of peace to a sobering awareness of the impact of war:

“… the news of this event, which consecrates afresh with the blood of our sons the ties that bind all men of British birth in one, brings home to us the greatness of the service laid upon the young men of this generation.”

The writer of the article continues:

“… these men who have jeoparded their lives unto the death are our own sons and brothers. But a few short months ago they were going in and out among us intent on the business and the pleasure of ordinary civil life, and not one of them, in his wildest flight of fancy, would have imagined that he would be called on before a year elapsed to face death at the cannon’s mouth in the far-off peninsula of Gallipoli. And now the call has come, and the men have been found faithful.”

A sense of what 25 April 1915 was like for those who were “facing death at the cannon’s mouth” can be gleaned from diaries kept by men who fought in the Gallipoli campaign. Corporal George Bollinger, for example, described it as a “beautifully fine day”:

“We are steaming full speed, close to the southern shores of Gallipoli. What a day of days! We left Lemnos at 6.00 am and continuously from 8.00 am we have moved amongst a roar of thunder. At present we are within a very few miles of our warships and transports, which are stationary here. What a sight! Their big guns never cease, and as we see the flash and burst of the shells on land, we think thousands of Turks must be going under. Has ever a bombardment like this taken place before? Our men are very calm, and some are even lying about reading and taking no notice of the bombardment. Boom, boom, boom. It never ceases. What batteries could reply to these 15 inch mouths of destruction.”

The next day, having been taken ashore, Bollinger’s diary reflects the sobering reality of the situation: “In landing as many as 49 were killed in one boat and a whole regiment was practically wiped out.” The situation continued to get worse as the week wore on. A similar realisation, albeit on a far slower timeframe, was subsequently experienced by those receiving the cables and news back home.

The 25th of April was officially named ‘Anzac Day’ in 1916 – though impromptu services and a half-day holiday for government offices were held when the news of the failed Gallipoli campaign reached New Zealand shores in 1915. By 1916 ‘observances respecting Anzac Day’ were official.

Although the traditions and legal status of the day have evolved over the decades, this is the ‘Anzac Day’ New Zealanders continue to observe.

25 April 1914: Life 100 Years Ago

But in 1914, months before the war that we now know as the ‘First World War’ was declared, 25 April was an ordinary Saturday. Apart from the South African War of 1899–1902 (sometimes known as the Boer War), in which fewer than 7000 New Zealanders had served, the country had no experience of overseas wars. New Zealand could not foresee the scale of what was coming.

Life 100 Years Ago is a collaborative online project, co-ordinated by the WW100 Programme Office, that shares excerpts from diaries, letters and newspaper reports 100 years later in ‘real-time’ on the web and on Twitter. Through these excerpts we in 2014 are able to get an insight into the daily lives of New Zealanders living in 1914. The project began in April 2013, with extracts from April 1913.

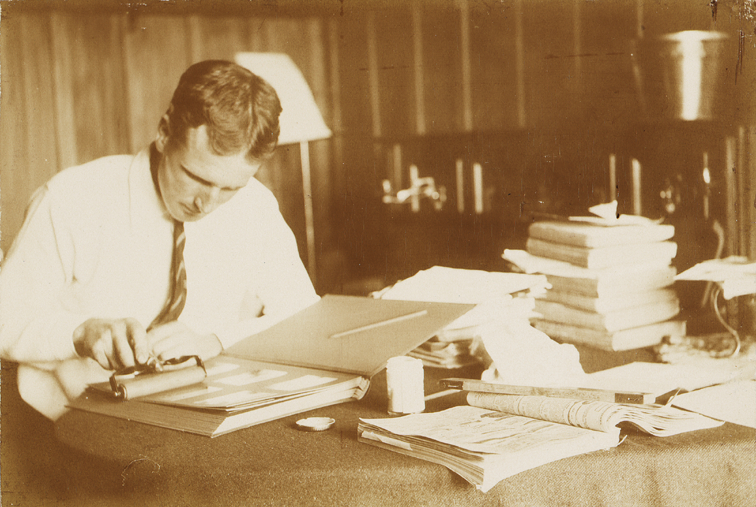

Leslie Adkin at work recording his life. Courtesy of Te Papa. Gift of G. L. Adkin family estate, 1964.

On 25 April 1914, for example, one diarist, 25-year-old Leslie Adkin, doesn’t yet know that his brother Gil will go to war and not return when he writes, “Gil & Jim went down to catch a train at 2.15 am en route for the Territorial camp.”

His uncle, Bert Denton, having a few months before led a group of “Massey’s Cossacks” in the Great Strike of 1913, does not know that in a couple of years he will depart for war, leaving behind his family – and his diary, which his family keeps for him while he is away. He doesn’t even remark upon 25 April 1914.

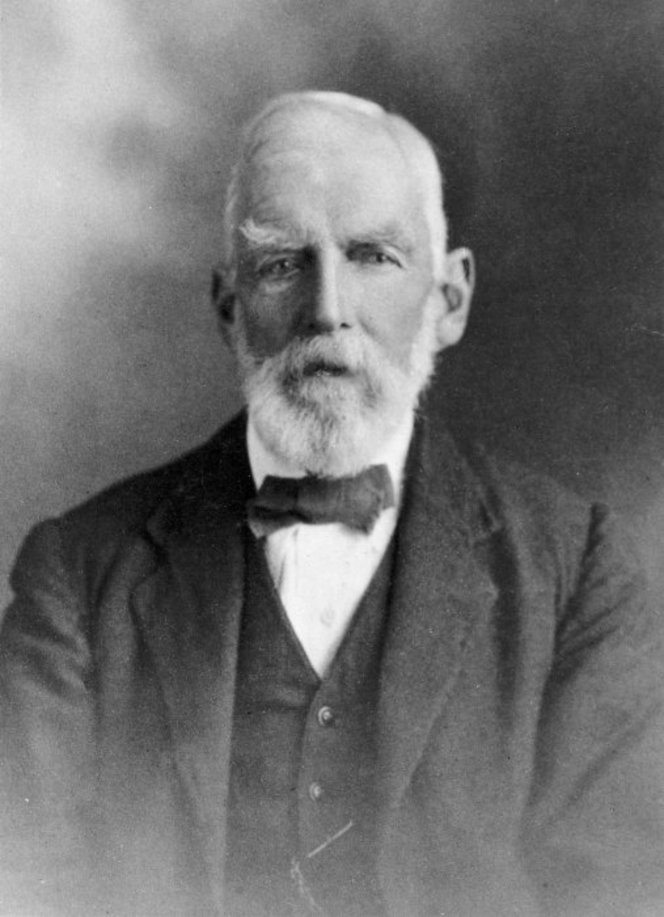

James Cox. Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/2-164539-F

Meanwhile, James Cox and Frederick Welch, both too old to serve, have no idea that in a year’s time they will be looking to the newspapers with the rest of New Zealand, many spurred by rumours that the New Zealanders had suffered severe casualties – ranging from 200 to 1400 depending who you talked to. On 25 April both of these diarists had an ordinary pre-war Saturday:

“No work today, I loafed all day. It is pay-day by the County Council. I got mine this afternoon £6.1.6” – James Cox, 68 years old.

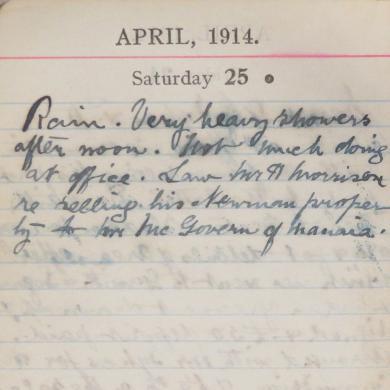

“Not much doing. Saw Mr H Morrison re selling his Newman property to Mr McGovern of Manaia” – Frederick Welch, 48 years old.

25 April 2015: Celebrating a centenary of peacetime

This Anzac Day, as 100 years ago, New Zealand was at peace on 25 April 2014.

We’d love to know what that means to you, and how you went about your day – the centenary of the last day 25 April was just 25 April. Leave us a comment below, or share your thoughts and experiences with us on Facebook or Twitter using the hashtags #peacetime and #anzac14.